5 Diagnostic methods

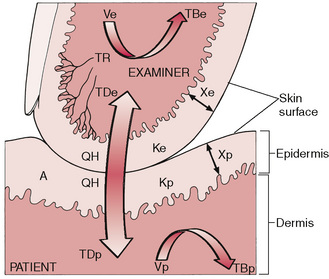

A great many diagnostic aids exist for discovering just what is happening when aspects of this network of tissues malfunction. The great beauty of neuromuscular technique, as devised by Lief, is the way in which diagnostic and therapeutic processes are combined. The thumb, as it glides close to the spinal attachments of the paraspinal musculature, is assessing the tissue tone, density, temperature, etc., and at the same moment is capable of treating any tissues that display evidence of dysfunction (see discussion of STAR characteristics – sensitivity, tissue texture alteration, asymmetry, reduced range of motion – in Ch. 3). The response of the searching thumb or finger to whatever information the tissues impart can be immediate. The use of greater or lesser degrees of pressure, varying in direction and duration, allows the practitioner to judge and treat at the same time, and with great accuracy (Figs 5.1 & 5.2).

Palpation

Palpatory diagnosis

Skin assessment before adding lubricant

Assessment after adding lubricant

Dysfunctional patterns revealed by means of assessment of skin changes should become apparent in the application of neuromuscular palpation/assessment strokes, as described in detail in Chapters 6 & 7.

Induration

A slight increase in diagnostic pressure will show whether or not the superficial musculature has an increased indurated feeling (‘dense’, ‘firm’, less elastic). When chronic dysfunction exists, the superficial musculature will demonstrate a tension and immobility, indicating fibrotic changes within and below these structures. These changes are discussed further in the text dealing with the application of basic spinal and abdominal NMT (Chapters 6 & 7).

Key questions

Deeper palpation: Peter Lief’s perspective

As Peter Lief (1963), son of the innovator of NMT, explains:

Youngs’ NMT description: tissue changes and objectives

Youngs (1964) has described what it is that the palpating fingers are seeking and finding and, as in NMT diagnosis and treatment often take place together, what they are achieving:

From this one can amplify Stanley Lief’s beneficial effects of neuromuscular treatment as follows:

1. To restore muscular balance and tone.

2. To restore normal trophicity in muscular and connective tissues by altering the histological picture from a patho-histological to a physiologic–histological pattern with normal vascular and hormonal response.

3. To affect reflexively the related organs and viscera and to tonify them naturally.

4. To improve drainage of blood and lymph through the areas subject to gravitational or postural stasis, e.g., abdominal vessels not necessarily connected with viscera.

Thus the hyperaemia, resulting from [NMT] treatment automatically operates to reverse the original patho-histological picture and consequently normality will be approached.

Trigger points

There is clinical evidence that trigger points have a consistent distribution, and their localization can be predicted by studying the patterns of referred dysfunction and pain to which they give rise. Similarly patterns of referred pain are predictable if the trigger point can be located (Travell 1957, Travell & Simons 1992).

A patient with unexplained pain, the examination of which reveals no local cause, may well have trigger points feeding pain messages into the target area. Thus the point at which the patient feels pain, and the point at which the pain originates, are often not the same, and knowledge of the reference patterns as illustrated in Chapter 3 (see Fig. 3.6) is therefore important.

Whether treatment of trigger points consists of anaesthetic injections, acupuncture, cryotherapy, or pressure and stretch techniques (NMT), or combinations such as INIT (see Ch. 9), the diagnostic aspect remains the same. Deep palpation and pressure on the located point must reproduce the symptoms in the target area in order to ‘prove’ the connection.

Zones of dysfunction: connective tissue changes

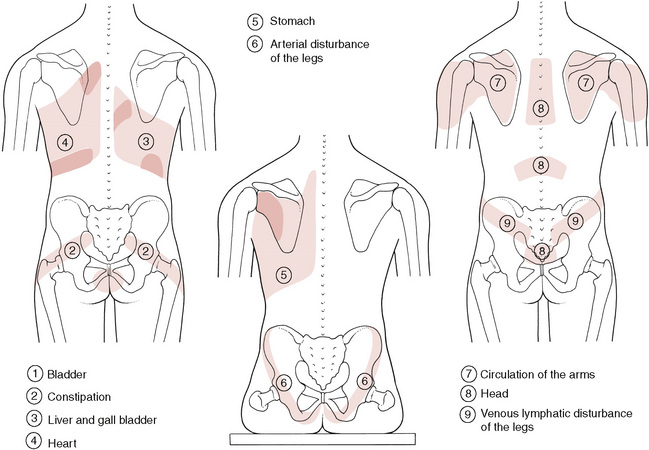

As well as trigger points there exist a number of palpable and often visible (Box 5.1) zones of soft tissue alteration, possibly involving viscerosomatic activity, in which diseased or stressed organs negatively influence soft tissues paraspinally and elsewhere (Bischof & Elmiger 1960). Viscerosomatic reflexes and the processes of facilitation (sensitization) were discussed in Chapter 3. Some of these zones overlap and incorporate ‘trigger’ points, so a general awareness and knowledge of their existence is useful if an understanding of what can be achieved in NMT is to be more complete (Fig. 5.3).

Box 5.1 Assessing the dominant eye

![]() In making a visual diagnosis it is important for the practitioner/therapist to be sure of the information he or she is acquiring. American osteopathic physician Edward Stiles (1984) made a valuable contribution to this area by pointing out that it is often for reasons of position, in observing structure, that a student or practitioner fails to see what is obvious:

In making a visual diagnosis it is important for the practitioner/therapist to be sure of the information he or she is acquiring. American osteopathic physician Edward Stiles (1984) made a valuable contribution to this area by pointing out that it is often for reasons of position, in observing structure, that a student or practitioner fails to see what is obvious:

• On the right side will be found the connective tissue reflex zones from the liver, gall bladder, duodenum, appendix, ascending colon, ilium, etc.

• On the left side will be found the reflex zones from the heart, stomach, pancreas, spleen, jejunum, transverse colon, descending colon, rectum, etc.

• Central zones occur as a result of dysfunction in the bladder, uterus and head.

• Changes on the homolateral side of the body occur due to dysfunction of the lungs, suprarenal glands, ovaries, kidneys, blood vessels and nerves on that side.

According to Teiriche-Leube & Ebner (quoted in Teiriche-Laube 1960), these changes in the connective tissue and muscles can take the following forms:

For Teiriche-Leube & Ebner’s description of some of these zones, see Box 5.2.

Box 5.2 Altered connective tissue zones resulting from disturbed organs and functions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree