25. Diagnosis – the key methods

Chapter contents

Introduction192

Colour192

Odour194

Sound196

Emotion199

The stages of emotion testing202

The testing process for each Element207

Introduction

This chapter covers the key methods of diagnosis used in Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. These are:

• colour

• odour

• sound

• emotion

Colour

The background

The colours associated with each Element are:

• Wood – green

• Fire – red/lack of red

• Earth – yellow

• Metal – white

• Water – blue

There are four significant places for a Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist to observe colour. These are by the side of the eye, under the eye, in the laugh lines and around the mouth. Some people’s colour shows in broad swathes on the sides of the face. The colour at the side of the eye is the most important area to notice when diagnosing the CF.

Sometimes at least two colours appear on the face. For example, there may be a green colour around the mouth and a different colour next to the eye. In this case the colour by the eye normally takes precedence. 1

One anomaly about facial colour is that Fire CFs, rather than showing a red colour, normally have a dull pale facial colour, especially at the sides of the eyes. This colour is called ‘lack of red’.

The difference between seeing and labelling

There are two distinct steps for the practitioner to take when learning to observe colour. Firstly, practitioners need to see the colour. Secondly, they need to be able to label it. Seeing is not the same as labelling.

Seeing colour

Some practitioners try to label colour before they have seen it properly. In this case they have left out the first step. They need to learn to see colour first. This can be an important part of the training when learning Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. More is written about this below.

Labelling colour

Other practitioners see a distinct colour but then do not know what to call it. Some people have a wider range of labels for colour than others. For example, a person who mixes colour for a paint manufacturer or a person who paints landscapes is likely to have more labels for different colours than solicitors or linguists who use their visual acuity less. It can be helpful if practitioners take the time to observe a wide range of colours, especially those seen in nature, in order to increase their colour ‘vocabulary’. Being able to label colour is essential as it links what practitioners observe with their Five Element diagnosis.

Seeing facial colour

In order to increase their ability to see colours, practitioners can set themselves certain tasks. For example, one task may be to spend 15 minutes sitting at the window of a café or restaurant observing the facial colour of those passing by. Another option may be to observe the colour of 10 different people during the course of a day. It may also be useful for practitioners to observe colour with a fellow learner and compare what they see. In order to fine-tune their skills, practitioners need to look at the facial colour of almost everyone they meet.

When observing colour, it is important that practitioners relax their eyes. Squinting, moving the head forward or getting anxious make it less likely that the practitioner will be able to discern the colour. Below we discuss how practitioners can develop their sensory acuity by:

• comparing colour

• observing in different lights

• being aware of how light is reflected

• softening their eyes

Comparing colour

Comparing colour increases sensory acuity. For example, looking at two faces simultaneously (or at least quickly moving back and forth) heightens practitioners’ visual awareness. Acupuncturists who are working on their own, looking at only one patient, can easily cross the habituation threshold. To focus their minds on the sensory input it can be useful for them to compare different areas of the patient’s face. This gives them several colours to observe. To help them to do this they can ask themselves a question, such as, ‘How do the colours on either side of the face compare?’ or ‘Which colour is paler?’ The landscape painter does this naturally as his or her eye travels back and forth from field to canvas and back again.

In a group, when people are learning to see colour, it can be useful to line up two to five people to compare their different colours.

Observing in different lights

Natural light is important when observing colour, so practitioners may sometimes need to ask patients to step outside or over to the window of the treatment room in order to find the best light. It is often useful to ask patients to face the light and to then turn their heads slowly from one side to the other. This will enable the practitioner to observe the facial colour on all areas of the face.

Observing in different lights can be useful as this helps the practitioner to understand the benefits of good light. Mid-winter in Britain is not a good time for natural light. The skies are greyer and the days are shorter. Many treatment rooms have little natural light and artificial light subtly distorts the true colour. Making comparisons between artificial and natural light, one side of the room and another, bright sunlight and soft northern exposure, enables a practitioner to get used to the effects of different lights. A change in colour will easily convince the practitioner that bringing the patient to the best source of light is a good idea.

Awareness of how facial colour can be distorted

Light is reflected off walls, blankets and clothes. A patient with a green shirt or pink blanket may appear different when wearing a brown shirt or using a blue blanket. It is useful for the practitioner to experiment and notice any differences caused by different lights.

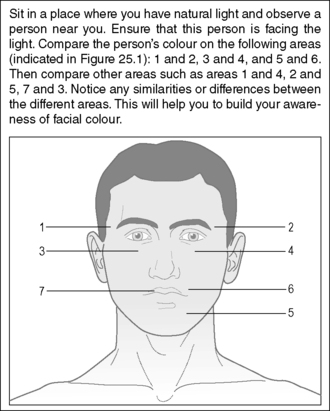

It can also be useful to remember that make-up distorts colours and the practitioner may need to ask some patients not to wear make-up on the day of treatment. Figure 25.1 describes an exercise to help develop the practitioner’s awareness of facial colour.

|

| Figure 25.1 • |

Softening the eyes

Hard eyes limit the range of our vision and make it difficult to see colour. The more we relax and soften the eyes the wider our vision and the better we can see the patient’s colour (Box 25.1).

Box 25.1

The following is an exercise to soften the eyes:

Two practitioners, A and B, work together and sit opposite each other.

A closes her or his eyes and then relaxes them as far as possible.

He or she then concentrates on the eye itself and just behind it.

When the eye feels somewhat different, A opens the eyes just for a second or two and looks at B’s colour.

A then closes her or his eyes and repeats the softening.

A then once more opens the eyes, this time for slightly longer and repeats until she or he experiences seeing the colour better and at the same time seeing ‘more’.

Labelling colour

Sometimes labelling is easy. The colour is obviously blue or obviously green. On occasions, however, there is a dispute as to whether that colour, which two people are both looking at, is yellow or green, or is it both or a mixture of the two? When there is disagreement, it is best to revert to observing the colour again and looking at it in the best light conditions possible. Confusion decreases over time, but some uncertainty may remain.

When practitioners are unsure of the correct label, the following method can help them to learn to identify colour. If, for instance, a practitioner can’t decide whether the patient’s colour is yellow or green, she or he can still make a diagnosis based on other factors such as the emotion, odour or voice tone. If that diagnosis is then confirmed by a positive response to treatment, then the practitioner might make an inference about the colour, based on the confirmed diagnosis. For example, if the treatment response confirms that the patient is a Wood CF, then in spite of the earlier confusion between yellow and green, the practitioner might conclude that the predominant colour was green. Learning in this way is probably the easiest way for practitioners to improve their ability to recognise colours. (The ability to recognise odour and voice tone can also be partly learnt in this way.)

Once the practitioner becomes aware that reflected colour can change the patient’s colour, it is inevitable on many occasions to ask the patient to stand in front of a window where the light is optimum. The practitioner can then ask the patient to turn their head slowly from side to side which presents the best conditions for viewing colour. It seems that shyness stops practitioners from doing this, but getting the colour right is far more important. This is also the best position in which to examine the tongue.

Odour

The background

The odours for each of the Elements are:

• Wood – rancid

• Fire – scorched

• Earth – fragrant

• Metal – rotten

• Water – putrid

As soon as there is an imbalance in a person’s qi, their odour will change. During the diagnosis the practitioner will endeavour to smell the patient’s predominant odour.

Smelling and labelling odours

Smelling odours

As with colour, smelling more keenly is an essential stage to go through before learning to apply the correct odour labels. After taking a case history, a common complaint from practitioners is that they didn’t smell an odour. The reason for this is simple. Most people do not need to be able to smell to get through their day. Apart from smelling smoke (indicating a fire), a gas leak or perhaps food to determine whether it has gone off, most people do not regularly use their ability to smell. Compared to a cat or dog, both of which will constantly be checking their environment for odour information, humans barely use their sense of smell. Thus to use odour regularly with patients requires some development.

Labelling odours

When practitioners learn to hone their sense of smell, they still have the problem of identifying the smells correctly. The labels for the odours listed above are not particularly helpful, as many people do not have clear ideas about, for example, the smell of rotten as opposed to the smell of rancid.

Increasing the ability to smell

One problem when smelling odour as opposed to looking at colour is that a colour is more constant and objective. If practitioners look at the colour by the eye, then look away again, they expect to look back and see the same colour again. This is especially true if they do it quickly and they or the patient do not change position or alter the light. This is less true with odour because people habituate to smells very quickly. This habituation is similar to what happens if we repeat a word endlessly and it seems to lose its usual meaning. We may initially smell something strongly, but then the smell quickly fades. The fragile nature of an odour is a matter of degree, but it is less constant and substantial than colour. Box 25.2 describes an exercise to help develop the ability to smell odours.

Box 25.2

The following is a short exercise to carry out while reading this book. Smell in sequence the front of your hand, the back of your hand, the sleeve of your shirt and then your shoe. Can you tell differences? Without trying to use the labels associated with each Element, can you give a name to the smells? If you were presented with them in random order, could you say which was which?

When to smell the odour

Because people habituate quickly, it becomes important to ‘catch’ odours by surprise. One of the best times for practitioners to smell a patient’s odour is when they have just entered the treatment room. If a patient has removed some clothing, the odour seems to fill a room and build up, especially if the patient has been in the room for several minutes. The practitioner can smell the hallway and then smell the room, in a matter of one to two seconds. In this way they can use contrast and comparison to accentuate the odour. After the practitioner has been in the room for more than a minute or two, the chances of detecting the odour become considerably less.

If a patient is lying under a blanket in a warm room this may also provide the practitioner with an opportunity to smell the odour. When the blanket is lifted in order to check the temperature of the three jiao or to carry out abdominal diagnosis a smell may be detected.

It can also be useful for practitioners to notice the odour in the area between a patient’s shoulder blades. The odour is often more distinct here as this is a difficult area for people to clean.

How to smell the odour

The more the practitioner is relaxed the easier it is to smell the odour. ‘Trying hard’ to smell is especially ineffective. Sometimes the odour becomes stronger and clearer when it is least expected. When a practitioner is deeply relaxed, for example, when taking pulses, the odour may suddenly become more apparent.

It is important for practitioners not to obviously sniff or show that they looking for an odour or rapport can easily be lost. The patient may wrongly conclude that the practitioner thinks she or he has an offensive smell!

Artificial smells

Another point the practitioner needs to remember is that patients are often wearing a number of artificial and acquired smells that cover up the underlying odour. These range from perfumes, hairsprays, what the patient last ate, deodorants, toothpaste, whatever is clinging to clothes (freshly dry cleaned or not) to flatulence. It is often appropriate for the practitioner to ask patients not to wear perfumes and other artificial smells on the day they come for treatment.

The labels of the smells

Most practitioners’ ‘smell vocabulary’ is less developed than their colour vocabulary. The vocabulary they do have often includes many judgmental words like ‘awful’, ‘yucky’ or ‘gorgeous’. These do not help a person to improve their ability to label odours. In Table 25.1 an attempt is made to describe the various odours.

| Element | Conventional label | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | Rancid | Like rancid butter or cut grass. Slightly prickly inside the nose and a bit musty at the same time |

| Fire | Scorched | Like clothes coming out of the tumble dryer or the smell of ironing or like burnt toast |

| Earth | Fragrant | Unlike ‘fragrant’ flowers. Heavy, cloying and sweet. A smell that hangs around the nostrils |

| Metal | Rotten | Like rotting meat or a rubbish bin or garbage truck where many different substances are decomposing. Grabs the inside of the nose with tiny prickles |

| Water | Putrid | Like a mixture of a urinal and chloride of lime. Can also be like stale wine, a tom cat’s spray or bleach. A sharp smell |

As with colour, one way practitioners can enhance their ability to recognise odours is to make a diagnosis using the other three key methods of diagnosis and then link the odour to that Element. Some practitioners are naturally gifted in the ability to smell odours, but for many it is their least developed sense. The challenge for them is to develop their ability to use it effectively. Box 25.3 suggests a practical way to improve the ability to distinguish smells.

Box 25.3

‘Smell-bottles’ are a useful device when learning to smell odours. Their purpose is to enable practitioners to:

• Increase the amount they consciously smell

• Refine their ability to make smell distinctions

• Increase their ability to remember smells

• Assist them in labelling smells

Smell bottles are not high-tech. All that is needed is to:

• Acquire five small, identical, opaque, containers that have tight-fitting tops to keep any material and its odour inside. These may be bought specially, but many foods and medicines come in these kinds of containers.

• Mark distinct numbers on the bottom, for example from one to five, and place something that is natural and has a distinct odour in each one.

• Open each bottle one at a time and get used to the smell. At this stage look at the number on the bottom.

• Mix the bottles up and open them one by one. Smell the contents and try to put them in the order of one to five.

This game enhances the practitioner’s ability to smell, discriminate, remember and possibly label the smells in order to remember them. There are many variations to the game above. For example, the practitioner can start with just two bottles and work up to five, or, to make the exercise more difficult, the contents of the bottles can be made more similar. This game can also be played with a partner.

Sound

The background and principles

The voice tones associated with each Element are:

• Wood – shouting/lack of shout

• Fire – laughing/lack of laugh

• Earth – singing

• Metal – weeping

• Water – groaning

A normal voice tone contains each of the five sounds when they are appropriate. When an Element is out of balance, one sound predominates or becomes absent. When there is reasonable balance these voice tones are appropriate to the emotion being expressed. When there is imbalance they are inappropriate. The Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist listens to the voice tone in order to determine which sound is most out of balance.

When learning to listen to voice tones, practitioners first need to be able to distinguish between a congruent or incongruent voice tone and emotion. They can then evaluate the voice tone in conjunction with the emotion the patient is expressing and the content of the discussion.

Voice tone and emotion

When people are relatively whole and balanced, their channels of emotional expression are also relatively balanced. For example, a shouting tone denotes anger or an attempt to assert oneself. To hear this sound when someone is actually angry is appropriate. To hear the same sound when a person is expressing love or warmth is inappropriate. Box 25.4 describes an experiment to help practitioners distinguish between congruent and incongruent sounds.

Box 25.4

To understand the difference between congruent and incongruent sounds and emotions, try this experiment. Feel friendly and say ‘hello’ in an angry tone. Feel sympathetic and express this in a frightened tone of voice. Try using other incongruent voice tones and emotions. Notice how often you hear these inconsistencies as you go about your daily activities. Often, without training, practitioners just accept these blatant incongruencies as ‘just how someone is’. They are, however, important diagnostically.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree