28. Diagnosis by touch

Chapter contents

Introduction223

Pulse diagnosis223

Feeling the chest and abdomen226

The Akabane test229

Introduction

Most of the methods of diagnosis discussed in this chapter involve touch. They are:

• pulse diagnosis

• palpating the three jiao or burners

• palpating the abdomen

• palpating the front mu points

• the Akabane test

These methods of diagnosis cover much of the ‘to feel’ aspects of diagnosis. This is the part of the diagnosis covered in the physical examination of a patient. Of these five areas, pulse diagnosis is by far the most important. Assessing the way the pulses respond during a treatment can be especially useful when diagnosing the CF. All of the other methods of diagnosis can indicate that an Element or Organ is significantly out of balance and can also support the CF diagnosis. They are, however, far less important in determining the CF.

Pulse diagnosis

The purpose and value of taking the pulses

Taking pulses by feeling the radial artery on the wrist is of one the most important diagnostic practices of Chinese medicine and practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture place enormous importance on it.

The main goals of pulse diagnosis are to:

• assess the level of qi of an Organ and Element

• determine whether the qi of an Organ or Element is excessive or deficient, thus governing the needle technique used

• help to diagnose any blocks to treatment (see Section 4, this volume)

• assess changes in the patient’s qi during and after treatment

How to take the pulses

The position of the pulses

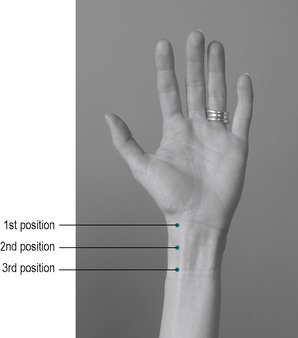

The pulses are felt on both wrists in three positions along the radial artery. The styloid process of the radius (shown in Figure 28.1) lies opposite the middle pulse position.

|

| Figure 28.1 • |

Position of the patient

When having their pulses taken the patient should:

• be relaxed, sitting or lying down

• have the arm free of obstructions such as watches, bracelets or tight sleeves

• have the arm level with, but no higher than, the patient’s heart

Position of the practitioner

When taking pulses the practitioner should:

• start by taking the pulses on the patient’s left-hand side, then the right

• stand at right angles to the patient and hold the patient’s left hand in their left hand as if shaking hands

• stand comfortably with a relaxed posture, weight evenly distributed and head held upright

Taking the pulses

When taking the patient’s pulses the practitioner goes through these stages:

• First, place the middle finger over the radial styloid until the tip reaches the radial artery. 1 At the same time use the thumb as a fulcrum at the back of the wrist.

1The use of the tip of the finger is probably a Japanese influence (see Eckman, 1996, pp. 206–207). Other traditions locate the pulse positions in the same place. They may, however, not hold the hand with the one that is not feeling the pulse and they may use the pads of the finger rather than the tips

• Next, let the middle finger drop on to the pulse of the middle pulse position.

• Having located the middle position, feel the first, second and third positions in turn. The first pulse position is distal to the middle position and is felt under the tip of the index finger. The third position is proximal to the middle position and is felt under the tip of the ring finger. When feeling each position, the practitioner should place only one finger on the artery at a time.

The two levels and the position of the Organs

The pulse is felt at two levels, superficial and deep. The superficial level is at the top part of the artery and is felt using light pressure. The deep level is lower down and is felt by using slightly heavier pressure. These two depths reveal the qi of the twelve yin and yang Organs. Table 28.1 shows the Organs in relation to the twelve positions.

| Left arm | Right arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Deep | Deep | Light | |

| Distal | Small Intestine | Heart | Lung | Large Intestine |

| Middle | Gall Bladder | Liver | Spleen | Stomach |

| Proximal | Bladder | Kidney | Pericardium | Triple Burner |

At different times in the history of Chinese medicine, slightly different pulse positions have been used (for a discussion of these, see Birch, 1992, pp. 2–13; Hammer, 2001, pp. 17–29; Maciocia, 2005, pp. 354–355 and Scott, 1984, pp. 2–7). Practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture use the positions laid down in the Nan Jing. Classical Chinese texts from the traditions of herbal medicine generally place the Kidneys at the third position on the right hand. Contemporary Chinese acupuncture texts usually place Kidney yang in the rear right-hand position, but this is a more modern (post 1949) development (see Birch, 1992, for a fascinating piece of research into the history of the placing of pulse positions in 101 different texts drawn from different periods in history).

Notating the quantity

Traditionally pulse diagnosis has determined the presence of up to 28 different qualities. Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturists focus on two, which are excess (full) and deficiency (empty). (Again, see Eckman, 1996. This emphasis on deficiency and excess is also a Japanese influence.) The overall fullness or emptiness is notated by using a numbering system ranging from −3 to +3 against the individual positions. Table 28.2 is an example of notating the pulses in this way.

| Left arm | Right arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Deep | Deep | Light |

| −1 | −1 | −1½ | −1½ |

| +1 | +1½ | ✓ | ✓ |

| −2 | −2 | −3 | −3 |

Feeling the quantity

When taking pulses the practitioner learns to discern the differences in strength between the different positions. At first the student concentrates on feeling the main differences, for example, the left middle position may feel stronger than the right middle position or the right first position may feel weaker than the right third position. After some experience has been gained by measuring this comparative strength, the practitioner attempts to find a ‘norm’ for the person.

The ‘norm’ in pulse taking

In order to find the patient’s ‘norm’, the practitioner considers the patient’s age, sex, physique and physical activity and decides on the level of strength that is a ‘✓’ or ‘just right’ for that individual. The norm for a young and strong person will be higher than that of an older and less strong person.

Having decided on the norm, the practitioner then records the pulses in relation to it. Some of the patient’s pulses may be stronger or weaker than the norm, so it is important that the practitioner bears in mind the level of the norm throughout pulse taking. Although this process is subjective, it has a sound basis in most practitioners’ experience. Almost all practitioners using any style of acupuncture will have experienced feeling a patient’s pulses and being surprised by their weakness or strength. This indicates that the practitioner has unconsciously decided on a norm. This is an important part of the diagnosis as most practitioners then look for an explanation for any apparent discrepancy.

Pulse changes during treatment and the overall change

So far the description of pulse diagnosis has outlined how practitioners can read the strength of individual pulse positions. Pulse taking in this way is crucially important because it reveals the strength of the qi in the Organs. There is also another reason for taking pulses, however. This is to consider the overall change that takes place in the pulses. This method is invaluable for both diagnosis and the evaluation of a treatment.

The overall view of the pulses

In order to feel this overall change in the pulses, the practitioner concentrates on how the different positions relate to each other. In this case the ideal is that the pulses are harmonious. Balance and harmony are more important than increasing the strength of an individual pulse position or even all the pulses.

When considering the notion of ‘harmony’, the practitioner will look for:

• the different pulse positions being similar in strength

• the different pulse positions being similar in quality

• similarity on one side of the pulses to those on the other

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree