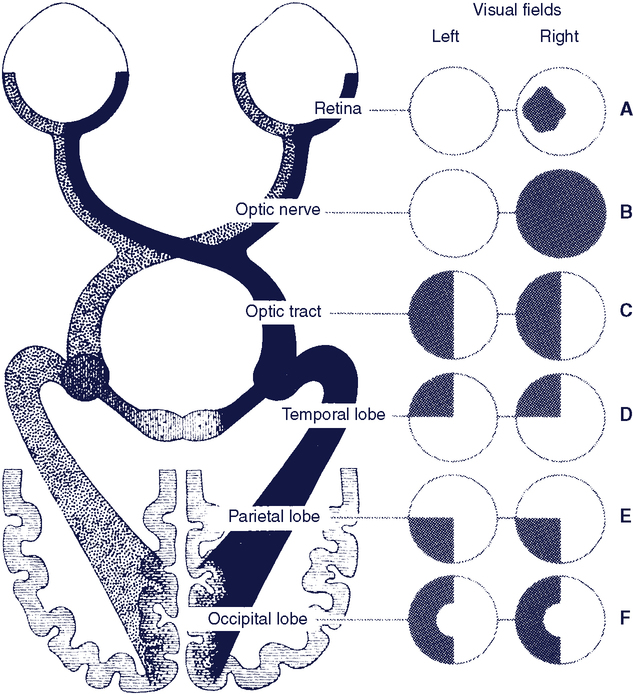

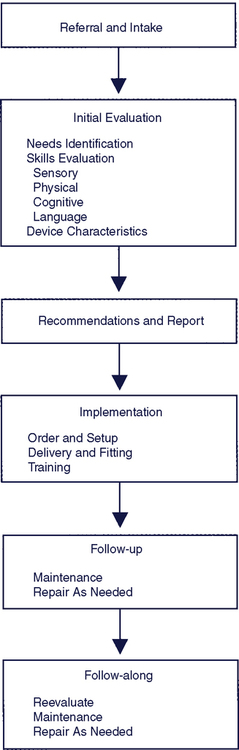

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Describe principles related to assessment and intervention in assistive technology service delivery 2. Describe the methods used to gather and analyze information during assistive technology assessment and intervention 3. Identify and describe each of the steps in assistive technology service delivery 4. Understand the need for training and describe strategies for the development of an effective training program 5. Describe the purpose of formal evaluation of assistive technology service outcomes 6. Describe the rehabilitation assistant’s role in the informal evaluation of assistive technology service outcomes 7. Describe different types of funding sources for assistive technology and considerations to make when determining eligibility for funding Service delivery is the provision of hard and soft assistive technologies to the consumer. In Chapter 1 we delineated the components of the assistive technology industry, which has at its core the consumer and service delivery programs. This chapter describes the process by which the consumer obtains assistive technology devices and services. Chapter 2 described a model that is used as the basis for assistive technology assessment and intervention (the Human Activity Assistive Technology [HAAT] model) and it discussed the principles of assistive technology system design. This chapter builds on the HAAT model by delineating systematic methods of assessment and intervention that help the team utilize components of the model and integrate them into an effective assistive technology system for each individual consumer. This chapter provides information on the full range of service delivery aspects, highlighting those elements in which the rehabilitation assistant has a primary role. To effectively provide these services to the consumer, the rehabilitation assistant should be knowledgeable in the following areas: 1. The principles related to assessment and intervention and methods of gathering and interpreting information. 2. The service delivery practices used to determine the consumer’s needs, evaluate his skills, recommend a system, and implement the system. 3. The measurement of outcomes of the assistive technology system that indicate whether the identified goals have been achieved. 4. The identification and attainment of funding for services and equipment. The assistive technology intervention begins with an assessment of the consumer. Through this assessment, information about the consumer is gathered and analyzed so that appropriate assistive technologies (hard and soft) can be recommended and a plan for intervention developed. Information is gathered regarding the skills and abilities of the individual, the activities she would like to perform, and the contexts, including social, physical, and institutional elements, in which she will be performing these activities. The assessment also yields information regarding the consumer’s ability to use assistive technologies. Based on the assessment results, a plan for intervention is developed. This plan includes recommendation and implementation of the system, follow-up, and follow-along. Basic principles that underlie assessment and intervention in assistive technology service delivery are listed in Box 3-1. Often AT assessment focuses on the assistive technology only, which can lead to later rejection or abandonment of the technology. One way to reduce the probability of abandonment or misuse is to consider systematically all four parts of the HAAT model. Needs and goals are often defined by a careful consideration of the activities to be performed by the individual. However, it is rare that the activity will be performed in only one context, so it is important to identify the influence of the physical, socio-cultural, and institutional elements in the contexts in which the activities will be performed (see Chapter 2). Thus the careful evaluation of the activities to be performed and the contextual factors under which that performance will occur are keys to success. Once the goals have been identified, an assessment of the skills and abilities of the human operator (the consumer) must be identified. Only after consideration of these three components (activity, context, and human) can a clear picture emerge of the assistive technology requirements and characteristics. The assessment process must also include an assessment of the degree to which these characteristics match the consumer’s needs. Chances of success in implementation of an assistive technology system are enhanced by attention to all four parts of the HAAT model during the service delivery process. This focus on function does not mean that an individual’s potential for improvement is ignored. The parallel interventions model1,44 demonstrates how technology can be used to promote the dual objectives of enabling function and improving an individual’s skill level. In one track, assistive technologies are provided that are based on the consumer’s current skills and needs in order to maximize his function. Simultaneously, a second track provides intervention that focuses on improving his skill level so as to minimize his reliance on technology. Some individuals who have a severe physical disability may have never had the opportunity to develop their motor skills, and training to develop these skills can take months or years.8 A common example is an individual whose evaluation shows that she is able to use her head to activate a single switch to make simple choices on a computer. With training and a period of experience in using this switch, her head control may improve to the point where she can use a light beam positioned on her head to make direct choices with a dedicated communication device. The latter means of control provides access that is faster and much less demanding cognitively. Progression toward the goals of the intervention plan is ongoing, with revisions to the plan as necessary. For example, during training, observation may reveal that the consumer can access the control interface more effectively if it is positioned at an angle instead of flat. This observation will result in adjustment to the position of the computer interface. The ideas of client-centered practice highlight the importance of involving the client at all stages of assessment, from the initial framing of the activities in which the client wishes to engage to the recommendation of an AT system.6 The client refers to the individual and others in their environment such as family and caregivers.6 Assessment is ongoing not only while the consumer is actively involved in the service delivery process, but also potentially throughout the consumer’s life. Because many individuals have lifelong disabilities, they will be in need of assistive technology throughout their lives. It is important not only to recommend assistive technology that enables the individual today but also to predict the technology that will be necessary to enable the individual in the future. The components of the HAAT model change over each individual’s lifetime. Changes may occur in the individual’s skills and abilities, life roles, and goals; in the capabilities of technology; and in the context in which the assistive technologies are used. Using the HAAT model as a framework, the team can predict some of these changes and plan for the consumer’s future technology needs. Given the nature of assistive technology and its impact on the consumer’s activities of daily living, it is essential that the assessment and intervention be a collaborative process. McNaughton (1993)31 defines a collaborator as “one who works with another toward a common goal” (p 8). Furthermore, she states that collaboration requires that (1) all participants be equal partners; (2) a problem-solving attitude be shared by all participants; (3) there be mutual respect for each other’s knowledge and the contributions each person can make, as opposed to the titles he or she holds; and (4) each participant has available the information necessary to carry out his or her role.31 These ideas are supported in the ideas of client-centered practice.6 There is a delicate balance between the “opinion” and “expertise” of the team (based on technical knowledge and experience with a variety of individuals) and the “opinion” and “expertise” of the consumer and family relating to their specific needs and goals. The consumer and family come to the assessment process with expertise in their daily lives, including the activities in which they need and want to engage, as well as expertise in the modifications and strategies they employ in the performance of these activities. The role of the team is to educate the consumer on the choices available to her so that she can make decisions related to the assistive technology in an informed manner. The challenge for the ATP is to do so without unduly influencing her choice. As identified above, AT is one component of the process of enabling activities. It may not be the consumer’s preferred method of performing activities. Beukelman and Mirenda (2005)4 discuss the importance of building consensus among the user, family members, and other team members. Negative consequences—such as a lack of vital information needed for the intervention; lack of “ownership” of the intervention, resulting in poor follow-through with the recommendations; and distrust of the service provider—may result if the process of consensus building is not begun during the initial assessment. Initiating this process early on helps to avoid problems in the future with regard to the acceptance and utilization of a device. The assessment process (either initial or ongoing) involves determination of what needs to be assessed and the most effective method of completing the assessment. It occurs in both formal and informal manners, using a variety of methods. Commonly, formal assessments involve use of standardized instruments, following the protocol established by the instrument developers.32 Informal assessment tends to occur on an ongoing basis, often involving observation or interview as the client is engaged in daily activities. Assessment includes gathering information on the client’s physical, sensory, language, and cognitive skills and emotional state; his performance in functional activities; the details of the settings in which these activities occur, including physical accessibility issues; social support; and institutional elements such as funding and policies around AT use and maintenance in those settings. The rehabilitation assistant may be involved in the data-gathering process using a standardized assessment providing that she has established competence in the administration of the assessment and that the use of the assessment is not restricted to specific professionals.45 For example, some cognitive tests are limited to use and score interpretation by only registered psychologists. More commonly, she will be involved in informal data gathering, particularly during the implementation phase of the AT service delivery process. The data gathered by the rehabilitation assistant provides useful information to guide the device selection process; thus she needs to be able to present her findings effectively in both written and verbal formats.45 She also needs to understand issues of measurement to appreciate the implications of the conclusions that are drawn from the data she has gathered.32 A framework to guide this data collection will be presented and discussed later in this chapter. A more thorough discussion of assessment formats, different types of measurements, and data gathering and interpretation follows in the section on initial evaluation of the AT service delivery process. Figure 3-1 illustrates the basic process by which delivery of services to the consumer occurs. The first step is referral and intake. Referral can be initiated by many different people, depending on the service delivery context. The consumer or a family member, a physician or another health care professional, or a teacher or other professional may make a referral for an AT assessment. The service provider gathers basic information and determines whether there is a match between the type of services he provides and the identified needs of the consumer. The purpose of the referral and intake phase is to (1) gather preliminary information on the consumer, (2) determine whether there is a match between the needs of the consumer and the services that can be provided by the ATP, and (3) tentatively identify services to be provided.19 The consumer, or the person making the referral on the consumer’s behalf, recognizes a need for assistive technology services or devices, which triggers the referral to the ATP. These identified needs are called criteria for service, and they define the objectives for the intervention. A third-party funding agency, such as a state vocational rehabilitation agency, may be involved at this stage. They will have a set of policies and procedures that governs who is eligible to seek assistive technology intervention and what devices and services they cover. Depending on the policies of the service provider, referrals are accepted from a variety of sources. These sources include the consumer, a family member or care provider, a rehabilitation or educational professional, or a physician. At this time, information regarding the consumer’s background and perceived assistive technology needs is gathered for the initial database. This information includes personal data (e.g., age, place of residence), medical diagnosis and health information, and educational or vocational background. Information related to the individual’s medical diagnosis and health information that may guide the assessment includes whether or not the condition is expected to remain stable, improve, or decline. The appropriateness of the referral is viewed from the perspective of both the ATP and the referral or funding source. When exchanging information about the consumer’s needs and the services provided by the ATP, each party can determine whether there is a match. For example, the needs of a consumer with complex seating and mobility needs may not match the services provided by the ATP if the ATP does not have the necessary expertise in this area. For the consumer’s benefit, this mismatch should be acknowledged and the consumer referred to another source that can more appropriately address her needs. The assistive technology provider should have a policy within the organization’s mission statement that establishes what services are provided and who is eligible to receive those services. For example, some assistive technology service providers specialize in certain disabilities (e.g., visual impairment), and others focus on specific technologies (e.g., seating technologies). Professional codes of ethics and standards of practice (see Chapter 1) require that ATPs practice within their specialization and not try to provide services outside of this realm. Throughout the assistive technology intervention, the team can gather information by either quantitative measurement or qualitative measurement. The philosophies of qualitative measures and quantitative measures are quite different. Quantitative measures assign a number to an attribute, trait, or characteristic.34 The assumption of quantitative measures is that the construct of interest can be measured in some meaningful way. For example, a test can be constructed that measures the joint range of motion (the construct) available to an individual to control a computer access device. Joint range is expressed as degrees of motion and a common understanding exists regarding what is meant when a specific joint range of motion is described. Here the construct can be assigned a number that is meaningful to individuals both using and interpreting the test. Alternatively, a test can be constructed that intends to measure boredom. For example, it is possible to develop a four-point scale and have individuals rate their boredom on it. But what does a score of “4” mean on such a scale? We can assign a number but it doesn’t carry any meaning. Two commonly used standards are employed for measuring performance (for both the human and the total system): norm referenced and criterion referenced. In norm-referenced measurements the performance of the individual or system is ranked according to a sample of scores others have achieved on the task. Norm-referenced measures usually produce a percentile rank, a standardized score, or a grade equivalent that indicates where the individual stands relative to others in the representative sample.49 It is important to review how the norms were developed when selecting a norm-referenced test for use. Norms need to be relevant to the population with which the instrument is being used. They need to be recent and representative.48 In other words, the characteristics of the sample used to develop the norms must be similar to those of the client group with which the assessment is being used. The items that form the instrument need to be relevant to the client group. For example, assessing visual-perceptual skills using blocks is not relevant for most adults. Similarly, the use of outdated questions or materials will not give an accurate picture of the client’s abilities. For example, testing keyboarding skills on a typewriter will give some information on keyboarding skills but does not cover the full range of skills required to use a computer.32 An alternative way to assess human or system performance is to rate the performance according to a specified criterion or level of mastery, which is referred to as criterion-referenced measurement, and the person’s own skill level in using the system is used as the standard. Criterion-referenced measurement requires that different degrees of competence in the functional ability to be measured can be expressed. One standardized method of achieving this description is through Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS).21 This method involves a consensus-driven process where a target behavior is identified and five levels of competence are clearly articulated. These are coded on a 5-point scale from − 2 to + 2. The zero point on the scale represents basic or minimum competence. The points below zero represent inadequate performance and those above zero are better than expected performance. Goals are specific, measureable, and time specific. Benefits to using GAS are that it is flexible, identifies performance over time, and is individualized to the client. However, it is time consuming and, because it is individualized, may not easily capture a range of functional activities. An example of GAS goals is shown in Box 3-2. The information for the needs assessment can be derived from an interview or through a written questionnaire completed by the consumer or his representative. Instruments such as the Matching Person and Technology Assessment42 can also be used by the ATP to identify the areas of the individual’s needs and his predisposition to use assistive technology. If the information is gathered through a written questionnaire before actually meeting the consumer, it should be reviewed at the time of the first meeting with the consumer. The purpose of reviewing this material at the first meeting is to ensure that all the necessary information has been provided and to analyze the information to develop the goals. In addition, the provider needs to ascertain that the consumer understands the questions that were asked. The total team should also be present at this meeting, and everyone’s input regarding the needs and goals of the consumer can be discussed and a consensus reached. A visual field deficit can be experienced in two ways: loss of peripheral vision or loss of central vision (Figure 3-2). Peripheral vision loss results in a narrowing of the visual field, commonly an age-related deficit.38,41 This type of loss makes it increasingly difficult to see objects to the side, potentially causing difficulties when maneuvering a wheelchair through a crowded environment. A central field loss has more significant functional implications because the individual loses the ability to see something they are looking at directly. Age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy are two common central field deficit disorders. Visual acuity refers to the clarity with which a person can see objects in the environment.38 The loss of this visual function is probably the best understood as it occurs so frequently in the population. There are three types: myopia (near-sightedness); far-sightedness; and presbyopia (the inability to focus on a near object), which is an age-related visual change. All of these functions result from an inability to focus the image on the retina. In most cases, functional vision is restored with the use of corrective lenses (glasses or contact lenses) or laser surgery. Chapter 8 discusses assistive technology to assist individuals with low vision or blindness, for whom these common interventions are inadequate. Visual tracking refers to the ability to track a moving object with the eyes; for example, tracking the movement of a cursor on a computer screen.15,38 Evaluation of visual tracking includes the coordination of both eyes, tracking ability in vertical and horizontal planes, smoothness of the movements, delay in the initiation of visual tracking, and the ability to track without moving the head. Visual scanning refers to the ability to scan the environment to gather visual information. In this situation, the object doesn’t move; instead, the eyes are moving.15 Visual scanning is most commonly used when reading text. Clients who have had a stroke may have a visual scanning impairment if they also have a neglect of one side of the body. In this situation, the eyes do not move past midline, so visual information on the affected side of the body is not detected. Visual contrast is required to differentiate a figure from its background, and is commonly used during reading and in retrieval of information from a display.41 With age and other visual impairments, contrast needs to be enhanced in order for the user to detect the information. Visual accommodation is the ability of the eyes to re-focus when shifting attention between different locations38; for example, shifting attention from the board to a notebook when taking notes during class or shifting attention from the road to displays on the vehicle instrument panel while driving. This function requires coordination of the small muscles of the eye. Visual perception is the process of giving meaning to visual information. Visual perceptual skills that need to be considered during the AT assessment include depth perception, spatial relationships, form recognition or constancy, and figure-ground discrimination. Visual perception is an important consideration when considering the client’s ability to interpret information presented in a visual display or to safely navigate a mobility device in their environment. Formal testing of the consumer’s visual perception may have been completed before the assistive technology assessment, and the results of this evaluation can be reviewed during the initial interview. The rehabilitation assistant may have completed parts of the visual perception assessment. It is necessary to observe the consumer during functional tasks and note any apparent perceptual problems. If there is still some concern regarding the exact nature of the problems, a formal evaluation such as the Motor-Free Visual Perception Test can be used.7 The typical range of frequencies that can be heard by the human ear is 20 to 20,000 hertz (Hz).2 However, the ear does not respond equally to all frequencies in this range. A combination of frequency and amplitude determine the auditory threshold. Pure tone audiometry presents pure (one frequency) tones to each individual to determine the threshold of hearing for that person. The intensity of the tone is raised in 5-dB increments until the stimulus is heard. It is then lowered in 5-dB decrements until it is no longer heard. The auditory threshold is the intensity at which the person indicates that she hears the tone 50% of the time.3

Delivering Assistive Technology Services to the Consumer

Principles of assistive technology assessment and intervention

Assistive Technology Assessment and Intervention Should Consider All Components of the HAAT Model: Human, Activity, Assistive Technology, and Context

Assistive Technology Intervention Is Enabling

Assistive Technology Assessment Is Ongoing and Deliberate

Assistive Technology Assessment and Intervention Require Collaboration and a Consumer-Centered Approach

Assistive Technology Assessment and Intervention Require an Understanding of How to Gather and Interpret Data

Overview of service delivery in assistive technology

Referral and Intake

Initial Evaluation

Quantitative and Qualitative Measurement

Norm-Referenced and Criterion-Referenced Measurements

Needs Identification

Skills Evaluation: Sensory

Evaluation of Functional Vision

Evaluation of Visual Perception

Evaluation of Auditory Function

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Delivering Assistive Technology Services to the Consumer