CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Degenerative lumbar stenosis is characterized by back and leg pain caused by narrowing, or stenosis, of the spinal canal. This narrowing, usually a degenerative condition produced by a combination of protrusion of the intervertebral disk and hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and articular facets, leads to compression of the neural elements with resultant buttock and radiating leg pain.

1 Symptoms of degenerative spinal stenosis typically do not manifest before the fifth or sixth decade. Lumbar spinal stenosis can also be developmental, idiopathic, or a consequence of metabolic bone diseases, such as osteopetrosis or achondroplasia.

Lumbar stenosis is often progressive with gradually increasing compression of the thecal sac, nerve roots, and rarely, the cauda equina. Most people with lumbar stenosis may be managed well with nonsurgical means.

2 Surgery, in the form of decompression with or without fusion, is reserved for patients who fail nonoperative management. Surgery for the well-selected patient typically leads to both short-term and long-term improvement.

3The spinal cord courses distally to about the first lumbar level. There, it terminates in the conus medullaris, from which nerve roots extend. The collection of lumbosacral nerve roots distal to L2 is said to resemble the tail of a horse and thus is designated the “cauda equina.” The cauda equina is housed within a thecal sac in the lumbar spinal canal.

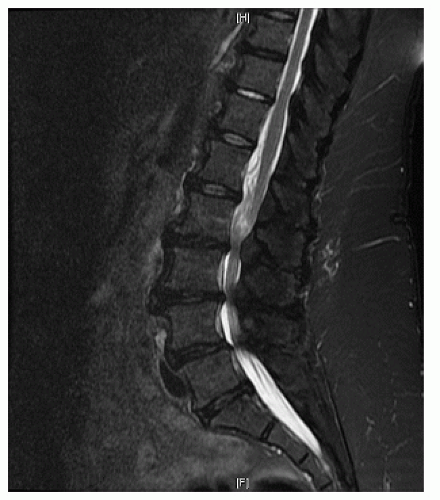

The spinal canal is the space surrounded by the disk and vertebral body to the front, the lamina and pedicles to the side, and the articular facets and spinous processes to the rear. In the lumbar region, the cross-sectional area of the canal is normally 100 mm

2, a space typically more than adequate for the nerves (

Fig. 3-1).

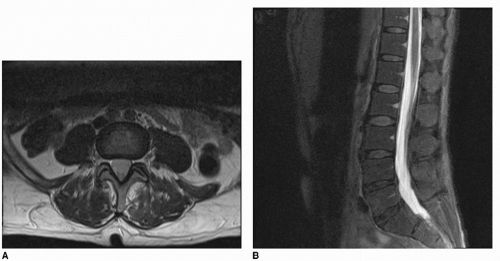

Lumbar stenosis is thought to start with subtle instability between vertebrae. In an effort to provide additional stability, there is a subsequent hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and articular facets. Unfortunately, this compensatory process crowds the neural structures, causing both mechanical compression and chemical irritation to the nerves (

Fig. 3-2).

Compression of the neural elements is likely once the cross-sectional area reaches <75 mm

2.

4 With compression, symptoms including low back pain, radiating buttock and leg pain, numbness and tingling in the lower extremity, and weakness may ensue.

5 Although many patients with spinal stenosis will describe “hip pain,” specifically asking about buttock and lower extremity radicular pain will help distinguish symptomatic lumbar stenosis from primary hip arthrosis, which often presents with groin pain.

Postural changes may have a significant effect on pain intensity. Standing and walking tend to exacerbate the pain, whereas sitting provides gradual relief. Patients almost invariably report limited endurance and complain of an inability to walk their usual distances without pain or fatigue. They frequently note that pushing a shopping cart eases the pain because this forward flexion allows the lumbar spinal canal and foramina to open. This type of pain is referred to as neurogenic claudication. Neurogenic claudication is at times designated “pseudoclaudication” to distinguish it from “classic claudication,” which is a similar condition of leg pain caused by vascular insufficiency. Because spinal stenosis and

vascular insufficiency are both associated with aging, it is not unusual for a patient to have both conditions. Distinguishing neurogenic from vascular claudication is clinically important because treatment options differ for each condition6 (

Table 3-1).

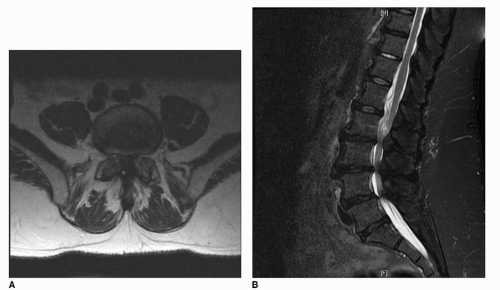

Acute cauda equina syndrome merits special discussion within the category of lumbar stenosis since it is a surgical emergency. Cauda equina syndrome is defined as a loss of lower extremity motor and sensory function, loss of bladder and bowel control, and perineal sensory deficit (“saddle

anesthesia”) due to severe compression of the nerve roots within the thecal sac below the level of the spinal cord.

Signs and symptoms of cauda equina syndrome include a progression of neurologic deficits over time. Normal urinary output over 8 hours exceeds bladder capacity, so urinary retention is often the first perceived symptom of a cauda equina syndrome. Although cauda equina syndrome is usually the result of an acute herniated disk, fracture, or expanding mass (e.g., tumor or hematoma), severe long-standing lumbar stenosis can rarely result in an insidious onset of cauda equina symptoms.

7