Surgical Decision Making for Stage IV Adult Acquired Flatfoot Disorder

Kyle S. Peterson, DPM, AACFAS∗ofacresearch@orthofootankle.com and Christopher F. Hyer, DPM, MS, Advanced Foot and Ankle Surgical Fellowship, Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Center, 300 Polaris Parkway, Suite 2000, Westerville, OH 43082, USA

Adult acquired flatfoot deformity is a debilitating musculoskeletal condition affecting the lower extremity. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) is the primary etiology for the development of a flatfoot deformity in an adult. PTTD is classified into 4 stages (with stage IV subdivided into stage IV-A and IV-B). This classification is described in detail in this article.

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction

Adult acquired flatfoot deformity

Deltoid ligament insufficiency

Introduction

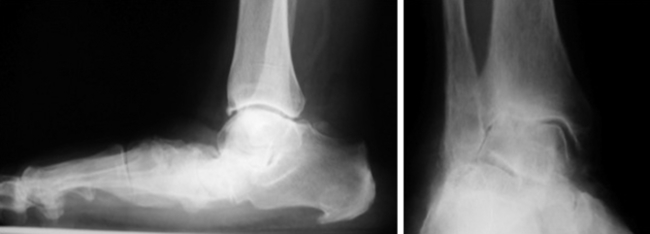

Adult acquired flatfoot deformity (AAFD) is a debilitating musculoskeletal condition affecting the lower extremity. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) is the primary etiology for the development of a flatfoot deformity in an adult.1 In 1989, Johnson and Strom created the most utilized classification for PTTD.2 Stage I PTTD is characterized by pain and edema along the medial aspect of the hindfoot and involves posterior tibial tendon tendonitis without associated hindfoot deformity. Stage II PTTD is depicted by a flexible flatfoot deformity with hindfoot valgus, forefoot abduction, and forefoot varus. Stage III PTTD is a more advanced disease causing a fixed, rigid hindfoot deformity. In 1996, Myerson modified the 3 stages of PTTD by adding a fourth stage involving the ankle joint.3,4 Stage IV PTTD occurs when the talus tilts into a valgus position within the ankle mortise (Fig. 1). This is caused primarily by insufficiency of the deltoid ligament.5 Recently, stage IV PTTD has been subdivided into stage IV-A and IV-B.6 Stage IV-A classifies patients with hindfoot valgus and a flexible ankle valgus without significant tibiotalar arthritis, while stage IV-B involves a rigid ankle valgus with significant tibiotalar arthritis.6

Anatomic considerations

Although the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) is the primary dynamic stabilizer on the medial arch, other anatomic structures contribute to the deforming forces on the hindfoot and midfoot. As the PTT assumes greater dysfunction and tendinosis, the peroneus brevis begins to act as an unopposed muscle, leading to increased hindfoot eversion. A contracted gastrocnemius–soleus muscle complex also leads to increased hindfoot eversion. Additional static ligamentous structures on the medial foot and ankle also contribute to the loss of the medial longitudinal arch, including the spring ligament complex, interosseous talocalcaneal, and the superficial deltoid ligament.7,8

The deltoid ligament consists of both superficial and deep fibers. The superficial band is a wide, fan-shaped portion that extends from the navicular to the posterior tibiotalar capsule and is incorporated into the superiomedial portion of the spring ligament.6 The deep portion of the deltoid ligament originates from the intercollicular groove and the posterior colliculus of the medial malleolus and inserts of the medial aspect of the talar body.9 Generally, the superficial deltoid is comprised of the tibionavicular, tibiocalcaneal, and tibiotalar ligaments, while the deep is composed of the anterior and posterior tibiotalar ligaments.9

Contributions from both the superficial and deep components of the deltoid ligament resist against tibiotalar tilting.10,11 Harper demonstrated in a cadaver study that division of both the superficial and deep components produced an average of 14° of valgus talar tilting.11 Earll and colleagues,10 in another cadaver study, showed a 20% to 30% increase in tibiotalar joint pressures and a 26% to 43% decrease in contact areas with sectioning of the tibiocalcaneal fibers of the superficial deltoid. Moreover, Rasmussen and colleagues12–14 have performed multiple cadaveric sectioning studies demonstrating superficial deltoid fibers contributing to the primary restraint of ankle valgus angulation.

Patient evaluation

Patients with stage IV PTTD will typically present similar to those with a rigid stage III foot. Additionally, stage IV patients will complain of medial ankle pain, often with an advanced valgus foot deformity. A history of associated ankle weakness and swelling is common. Patients frequently present with a multitude of failed braces, orthotics, and shoes. In those patients with severe ankle valgus, lateral ankle pain may also cause pain and debilitation. As the ankle valgus becomes more of a fixed deformity, forces are transferred to the fibula, where a stress fracture is possible, termed Johnson stage V disease.15 Patients are unable to perform single or double heel rise tests. The rigidity of the talonavicular and subtalar joints will be evident with manual range of motion. The ankle joint will be painful on palpation, and a determination of whether the ankle deformity is fixed or flexible should be noted. The gastrocnemius–soleus muscle complex and peroneal tendons will often be contracted.

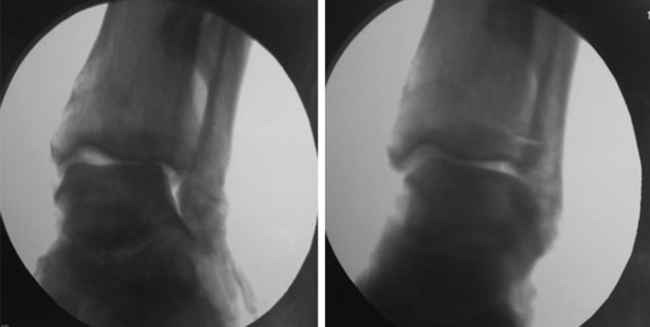

Weight-bearing anteroposterior and mortise ankle images will demonstrate increased tibiotalar valgus tilting with stage IV PTTD. In addition to the valgus tilt present in the ankle, the magnitude of tibiotalar arthritis should also be determined. When a valgus talar tilt is recognized in a patient with AAFD, the ability to passively correct the deformity needs to be tested. Evaluation is performed by manually applying a varus force of the joint under direct fluoroscopy (Fig. 2). If needed, contralateral comparison radiographs and stress fluoroscopic films may be necessary. Advanced imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be of benefit to evaluate the integrity of the posterior tibial tendon, deltoid ligament complex, and degeneration present in the ankle and hindfoot.

Treatment of stage IV

Nonoperative management of AAFD relies on supporting the foot externally with braces or orthotics. Management of earlier stages is successful with rest, immobilization, anti-inflammatory medications, and physical therapy.16 Stage IV AAFD, however, is difficult to treat conservatively, and treatment is often unsuccessful.17 The standard University of California Biomechanics Laboratory inserts are usually ineffective at controlling the rigid deformity of the foot and off-loading the ankle valgus. Custom molded ankle–foot orthoses and Arizona style braces can be of benefit in stage IV; however, pain and advancing tibiotalar arthritis may not be adequately corrected.

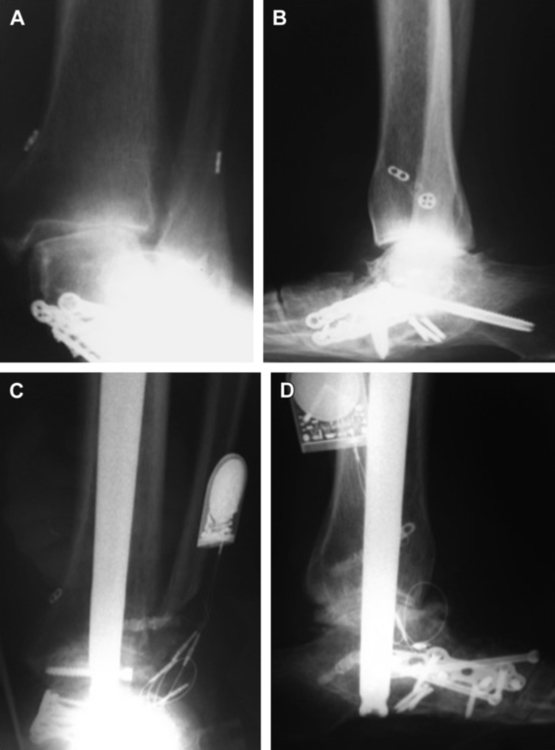

With conservative treatment oftentimes failing, surgical management is indicated frequently in stage IV patients. There is no gold standard on which to base surgical treatment for stage IV. Historically, tibiotalar valgus tilt with some extent of arthritis has been treated with a tibiotalar fusion.15 The rigid flatfoot that remains, however, still needs to be treated, which leads to selective hindfoot fusions in addition to the tibiotalar fusion. This creates the standard tibiotalocalcaneal or traditional pantalar fusion for a patient with stage IV AAFD (Fig. 3).5 These major hindfoot and ankle fusions have been successful in re-establishing alignment, but often create residual pain and stiffness.18,19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree