Chapter 1 Curriculum Design for Physical Therapy Educational Programs

Dr. Katherine Shepard shared this story, which has a powerful moral for all educational programs, in previous editions of this text and revisited the story in her McMillan lecture.1 “In 1983, the physical therapy program at Stanford University was suddenly and without warning told by the Stanford Medical School that we were to terminate the program.” The physical therapy program at Stanford University had been associated with the University since the 1920s and had advanced degree programs since 1940. As a young faculty member in the early 1970s, I assumed we belonged at Stanford just as much as any other department in the university. I never realized how changing the philosophy, mission, and expectations in other parts of the university could affect the very existence of our program. In 1982, the School of Medicine changed its mission from developing physicians to developing physician-researchers (MD-PhDs) and covertly designated the land on which the physical therapy building was located as the new center of Molecular Genetic Engineering. Subsequently, an all-physician review committee informed us that we didn’t belong in the School of Medicine because we didn’t have a PhD program and weren’t producing “scholars.” While meeting with the university president on an early spring evening to plead our case, he informed us that if we were to be considered scholars we should be publishing in the Journal of Physiology (his field was physiology) and not Physical Therapy (a technical journal by his standards). It was devastating to belatedly realize how the pieces were being put in place to discontinue our program. Our own mission statement, philosophy, and program goals were essentially ignored because they were now incongruent with the new university-sanctioned “direction” of the medical school. The Stanford University Board of Trustees acted to close the program with the graduating class of 1985.1 The moral of this story is that the philosophy and goals of any physical therapist or physical therapist assistant program must be in concert with the philosophy and goals of the program’s institution or the program will not survive.

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. State the core questions that guide curriculum design2 and describe the three-phase process of how faculty engage in curriculum development.3

2. Defend the need for a clearly stated program philosophy and goals to guide curriculum planning. Demonstrate how program philosophy and goals can be articulated and integrated with institutional mission, societal needs, and professional expectations and functions.

3. Distinguish the formal from the informal curriculum, applying the concepts of implicit, explicit, null, and hidden curricula to the specific educational setting.

4. Describe the role of curriculum alignment as an organizing strategy for program development.

5. Discuss main trends in health professions education that affect curriculum development and dynamic reform, including perennial challenges (and opportunities) between the curricular needs of health care professional programs and liberal arts education, growing demands for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration, and health professions’ role in meeting societal needs.

6. State the purpose of professional accreditation and outline the process of accreditation used by the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE).

Curriculum design

Everything depends on the quality of the experience that is had. The quality of any experience has two aspects. There is an immediate aspect of agreeableness or disagreeableness, and there is its influence on later experiences. The first is obvious and easy to judge. The effect of an experience is not borne on its face. It sets a problem to the educator. It is the educator’s business to arrange for the kind of experiences that, although they do not repel the student, but rather engage the student’s activities are, nevertheless, more than immediately enjoyable because they promote having desirable future experiences. Hence, the central problem of an education based on experience is to select the kind of present experiences that live fruitfully and creatively in subsequent experiences.4

A curriculum design reflects input, directly or indirectly, from literally thousands of people. People with health care needs, regulatory bodies, such as regional and professional accreditation groups and state board licensing agencies, members of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) who establish and act on professional standards,5 physical therapy clinicians, faculty and administrators in the college or university in which the program is located, and each generation of students have an impact on curriculum design. A curriculum design must be steadfastly relevant to the current tasks and standards of physical therapy practice and dynamically responsive to rapidly changing practice environments and human health care needs.

Developing a curriculum

Eliot Eisner noted that the word curriculum originally came from the Latin word currere, which means “the course to be run.” He states, “This notion implies a track, a set of obstacles or tasks that an individual is to overcome, something that has a beginning and an end, something that one aims at completing.”6

Tyler’s four fundamental questions

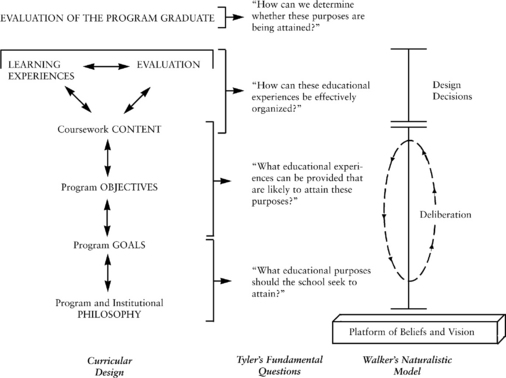

Four fundamental questions identified by Ralph Tyler in 1949 are useful in deciding how to develop a “racecourse.”2 These four questions are rediscovered by each generation of faculty seeking to develop a physical therapy curriculum.

1. What educational purposes or goals should the school seek to attain?

2. What educational experiences can be provided that are likely to attain these purposes?

3. How can these educational experiences be effectively organized?

4. How can it be determined whether these purposes or goals are being attained?

In designing a curriculum, the elements must be logically ordered. This logic can be obtained by thinking about how each level is directly responsive to the levels above and below. As illustrated in the curricular design column in Figure 1-1, the content of a physical therapy educational program (i.e., coursework, learning experiences, and evaluation and assessment processes) is based on meeting program objectives designed to fulfill the program’s goals. The program goals reflect the philosophy of the program and the mission of the institution. Evaluation of the program and assessment of student learning and graduate performance therefore demonstrate the success or lack of success of the program’s ability to build a curriculum that meets its stated goals.

Tyler’s Question 1: Program Philosophy and Goals

Macro Environment

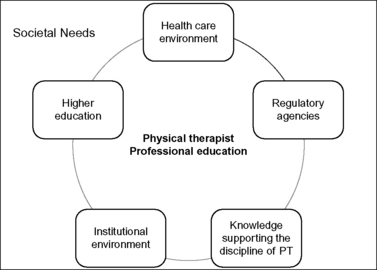

A good strategy for looking at the macro environment is to engage in an environmental scan. This includes a look at trends and issues outside of the discipline of physical therapy as well as other external influences that need to be considered in being responsive and dynamic. Figure 1-2 demonstrates how the philosophy and goals of any physical therapy curriculum are imbedded in a global (macro) environment that includes society, the health care environment, regulatory agencies, the higher education system, the institution in which the program resides, and the knowledge supporting the discipline of physical therapy.

When any component of this macro environment changes, it is necessary to engage in reflective, deliberative discussion and consider potential changes in the physical therapy curriculum. Looking both inside and outside the profession is part of an environmental scan that is important in designing a socially responsive curriculum. Here are some examples to consider. Historical changes outside the profession (e.g., medical discoveries such as the Sabin polio vaccine or the role of the genome) and inside the profession (e.g., the creation of the physical therapist assistant and the continued growth of clinical specialization) and national initiatives (e.g., patient safety or increasing importance of public health) have led to curricular changes.7–9 More than 20% of the U.S. population will be older than 65 years in 2030.10 Advances in technology and care along with pressures for reduced costs have resulted in decreased patient care stays in acute care and rehabilitation hospital settings. Physical therapy direct-access state laws have spawned curricular changes in entry-level and advanced coursework for physical therapists and physical therapist assistants. Other changes include the federal government support of health and health promotion and prevention activities seen in Healthy People 2020, which outlines a 10-year agenda for improving the health of the nation.7 Social determinants, such as employment, level of education, and living environment, all contribute to health outcomes. There is increased emphasis on preparation of health professionals who are collaboration ready, can work on teams, and understand the need for promoting health in communities as well as with individuals.11,12 The focus on health and wellness rather than disease, interprofessional team competencies, and community health are captured in Chapters 7, 12, and 15. There are many sources for performing environmental scans that range from looking at trends in higher education through the media and other literature to a regular look at health policy changes and new initiatives. The Institute of Medicine issues position papers13 and panel documents on critical health issues, which are excellent sources of information.

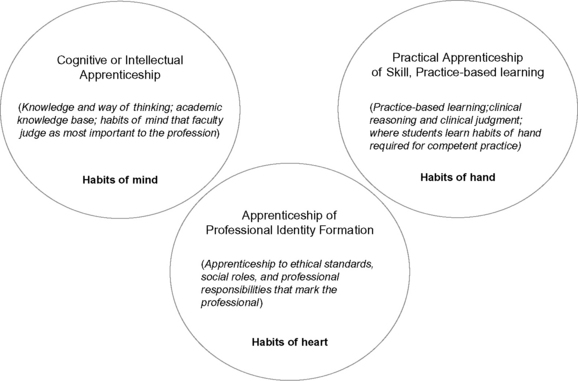

An example of important work in professional education is the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s comparative study of five professional fields (law, engineering, the clergy, nursing, and medicine).14–18 This research was grounded in a shared conceptual framework applicable to all professions that focused on the three major dimensions of professional education: knowledge (habit of mind), both theoretical and practical; practical skills (habit of hand), and professional identity (habit of heart). One of the most critical findings was that, given the lack of public trust in some professions, professional education must be clear about its social contract and engaged in cultivating the life of the mind for the public good (Figure 1-3). What the student is to know (i.e., the language of the discipline and the ways of science) is only part of what people who engage in curriculum design must include. Students must also be prepared to reason, to become sensitive and responsive to cultural diversity and society’s needs, to undergird decisions and actions with empathy, and to begin a quest for knowledge that will last throughout their professional lives.19 Professional education is the portal to professional life and an essential component of laying the groundwork for professional formation.

Health professionals must better organize professional education around what actually happens, as well as what should happen, in clinical practice. For example, students must be taught thinking and insight skills, such as reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, and intellectual humility as well as social responsibility to prepare them for the complex, unique, uncertain, and challenging health care situations they will face.19,20 Students need to be “collaboration ready” to work on interprofessional teams. Clearly, the knowledge, critical thinking and practical reasoning skills, humanistic skills, and professional responsibility and obligations and the ability to take moral action could be incorporated into the goals of any physical therapist or physical therapist assistant program.

Macro Environment: Body of Knowledge Related to Physical Therapy

The APTA monographs, A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education: Version 2004,5 which incorporates the document “Professionalism in Physical Therapy; Core Values,” and A Guide to Physical Therapy Practice,21 continue to provide a grounding structure for physical therapy educators. These monographs help educators define the body of knowledge related to physical therapy. In addition, the APTA vision statement for the profession is another foundational element for curriculum consideration.22

One of the main functions of the Normative Model is to “provide a mechanism for existing, developing, and future professional education programs to evaluate and refine curricula and integrate aspects of the profession’s vision for professional education into their vision.”5

The Normative Model is based on 23 practice expectations that define the expected entry level performance of a physical therapist. Educators can use this monograph to review how their coursework in Foundational and Clinical Sciences relates to examples of content, terminal behavioral objectives, and related instructional objectives in academic and clinical settings suggested by content experts. Although certainly not exhaustive, the suggestions can be extremely helpful, especially in guiding novice physical therapy instructors as well as those program faculty who are not physical therapists (Box 1-1).

Box 1-1 Example of Information in the Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education

| Primary Content | Examples of Terminal Behavioral Objectives (After the completion of the content, the student will be able to…) | Examples of Instructional Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptations to regular exercise of various types (aerobic or endurance training, interval or anaerobic training, muscle strengthening programs) Exercise specificity Effects on cardiovascular and pulmonary systems, metabolism, blood lipid levels, and skeletal, connective tissue, hormonal systems Hormonal changes with exercise and aging | Describe neural and muscular adaptations that occur as a result of resistance exercise training based on age, gender, and culture. | Describe changes in maximal oxygen consumption, submaximal heart rate and blood pressure, and maximal and submaximal ventilation that occur as a result of endurance exercise training. Describe changes in capillary density, oxidative enzymes, and mitochondria that occur as a result of endurance exercise training. Discuss the effects and side effects of the use of hormones and steroids for improving muscle strength. Differentiate the effects of aging and gender and exercise on hormones, including cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, and insulin. |

Data from American Physical Therapy Association Education Division. A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education: Version 2004. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2004.

A Guide to Physical Therapy Practice presents the current practice of physical therapy by outlining common practice roles and defining the types of tests, measures, and treatment interventions commonly used by physical therapists.21 In addition, preferred practice patterns are offered for four body systems: musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, cardiopulmonary, and integumentary. Each of the sections on preferred practice patterns contains the patient/client diagnostic group being considered; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes23; types of examinations, tests, and measures; anticipated prognosis; expected number of visits per episode of care; patient care goals and related physical therapy interventions and anticipated outcomes; and prevention and risk factor reduction strategies. Thus, the guide is rich with information that can be used by educators teaching and students learning clinical course content. In addition, Vision 2020, the APTA’s official vision statement for the future of physical therapy, provides several key strategic elements for the profession (e.g., educational preparation, direct access, professionalism).22

Another important document is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).23 The domains in this model are classified from body, individual, and societal perspectives and provide a means to look at an individual’s functioning and disability in a context that includes environmental factors such as social support. The ICF model is the World Health Organization’s framework for measuring health and disability and an important concept for physical therapy.

Micro Environment

Although there are shared expectations and standards for physical therapist and physical therapist assistant education, there is also the unique imprint of the institution and the program faculty that distinguish graduates across programs. Table 1-1 demonstrates two examples of how the mission and values of the institution are seen aligned across all levels (institution, school, and department). In the private institution example, the philosophy of the physical therapy curriculum at Creighton University reflects the “inalienable worth of each individual.” It also shows the emphasis on moral values in mission statements of the university and the school in which the physical therapy program is located. The public institution example reveals the connection that the School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences has as part of the College of Medicine.

Table 1-1 Two Examples Demonstrating Alignment of Missions across Institution, School, and Department

| Private, Faith-based Institution | Public, Research Institution |

|---|---|

| From mission statement: Creighton University Creighton exists for students and learning. Members of the Creighton community are challenged to reflect on transcendent values, including their relationship with God, in an atmosphere of freedom of inquiry, belief, and religious worship. Service to others, the importance of family life, the inalienable worth of each individual and appreciation of ethnic and cultural diversity are core values of Creighton. | From mission statement: University of South Florida USF is committed to promoting globally competitive undergraduate, graduate and professional programs that support interdisciplinary inquiry, intellectual development, knowledge and skill acquisition, and student success through a diverse, fully-engaged, learner-centered campus environment. |

| From mission statement: School of Pharmacy and Health Professions at Creighton University The Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health professions prepares men and women in their professional disciplines with an emphasis on moral values and service to develop competent graduates who demonstrate concern for human health. This mission is fulfilled by providing comprehensive professional instruction, engaging in basic science and clinical research, participating in community and professional service, and fostering a learning environment enhanced by faculty who encourage self-determination, self-respect, and compassion in students. | From mission statement: School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences The mission of the University of South Florida, School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences, is to prepare doctors of physical therapy who have a strong foundation in the basic and clinical sciences, and who demonstrate excellence in patient/client management, critical thinking and professionalism. |

| From Creighton’s departmental program philosophy The faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy affirm the mission and values of Creighton University and the School of Pharmacy and Health with the recognition that each individual has the responsibility for maintaining the quality and dignity of his/her own life and for participating in and enriching the human community. | From statements of educational philosophy of the School We believe interprofessional experiences enhance the future collegiality of healthcare professionals. Respect for individual and cultural differences is necessary for professional effectiveness in a global society. |

From Department of Physical Therapy, School of Pharmacy and Health, Creighton University, Omaha, NE; University of South Florida, School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tampa, FL.

The philosophy, mission, vision, and core values provide a foundation for the explication of educational outcomes for students. Box 1-2 lists the educational outcomes for a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) program that are divided into Professional Core Abilities and Physical Therapy Care Abilities. The Professional Core Abilities are shared across three health professions in the School (physical therapy, occupational therapy, and pharmacy) and reflect many of the core values of a Jesuit institution.

Box 1-2 Example of Educational Outcomes for a Doctor of Physical Therapy Program

From Creighton University, Doctor of Physical Therapy Program, Omaha, NE.

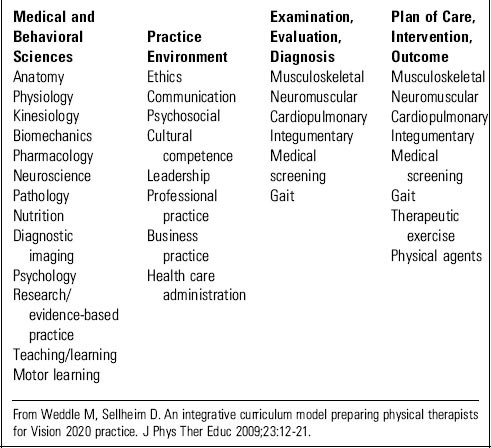

Tyler’s Question 2: Educational Experiences

Once goals and philosophy are understood, the next question to be answered is what educational experiences (classroom, laboratory, and clinical) are needed to achieve these purposes. Coursework in physical therapist and physical therapist assistant programs consists of foundation sciences, including both basic and applied across biological, physical, and behavioral sciences; and clinical sciences, including knowledge, skills, and abilities across body systems to understand diseases that require the direct intervention of physical therapists for management as well diseases that affect conditions managed by physical therapists and clinical education. The actual coursework designed and offered depends on the program’s practice expectations and the type and depth of prerequisite coursework. Matrices or tables can be very effective tools for mapping out the integration and implementation of courses and course sequences linked to the curriculum model.24 Box 1-3 provides an example of an integrative curriculum model designed to address future practice that matches curricular threads with specific content.25