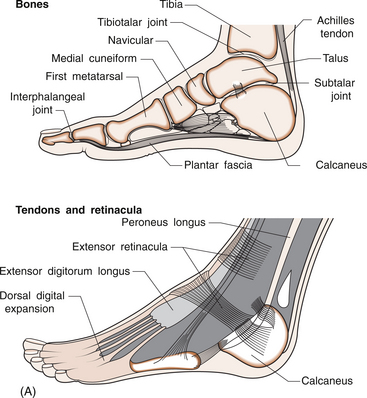

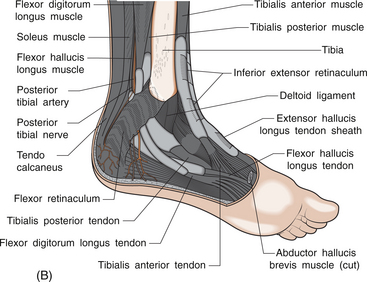

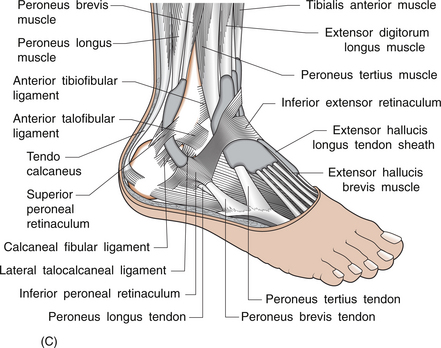

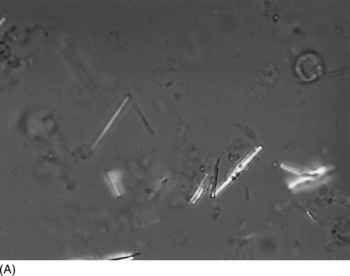

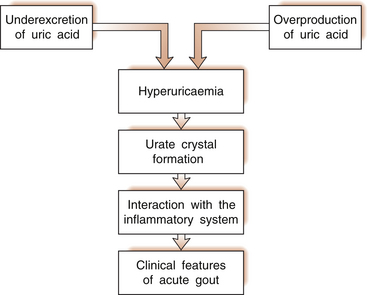

7 Neil McGill As discussed in Chapter 1, an acutely painful swollen joint can be explained by bacterial infection, crystal-induced inflammation (gout or pseudogout), trauma, haemarthrosis (bleeding into the joint) and occasionally by disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or reactive arthritis. The postoperative period is a time of increased risk for acute crystal-induced arthritis, particularly gout. Invasive procedures also have the potential to cause bacteraemia that could lead to septic arthritis, although the risk of that occurring at the time of a sterile procedure such as arthroscopy is very low. One could consider the possibility of trauma (e.g. while anaesthetized) but for trauma to produce a red, swollen, warm joint, the injury needs to be substantial. Thus, the most likely diagnoses are crystal-induced arthritis or sepsis. They both typically produce an abrupt onset of marked joint inflammation. The ankle region comprises three joints: 1. the true ankle (tibiotalar) joint between the tibia and the talus 2. the subtalar joint between the talus and calcaneus 3. the talonavicular joint between the talus and the navicular (Fig. 7.1A). Involvement of any of these three joints will cause ‘ankle’ pain. The tibiotalar joint is a true hinge joint whose movement is almost entirely limited to plantar flexion (downwards) and dorsiflexion (upwards). The fibula articulates on the lateral side of the tibia but does not bear weight. The subtalar joint allows the foot to be inverted or everted. The midtarsal joints, including the talonavicular joint, allow forefoot supination and pronation. The articular capsule is lax on the anterior aspect but tightly bound on both sides by strong medial and lateral ligaments. All the tendons crossing the ankle joint lie superficial to the articular capsule and are partly enclosed in synovial sheaths (Fig. 7.1B). Disorders of the peroneal tendons (inferoposterior to the lateral malleolus), the tibialis posterior tendon (inferoposterior to the medial malleolus), the tendons that run anterior to the ankle joint (such as tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus) or the Achilles tendon also cause ‘ankle’ pain. Which structure is responsible for the patient’s pain can often be determined by testing specific movements and the patient’s ability to resist movement in specific directions. The tibialis posterior muscle helps to maintain the ankle in a position of inversion, and the peroneal muscles help to maintain eversion. The synovial fluid obtained should be examined promptly; including macroscopic appearance, cell count, Gram stain, culture and microscopic examination for crystals. In Chapter 1 we described the characteristics of synovial fluid in normal and abnormal joints. Here, we will consider only those aspects of synovial fluid analysis that apply to crystal identification. Examination for crystals requires only a tiny amount of synovial fluid (even an apparently ‘dry’ tap may yield enough) but the examination should be performed immediately. Polarized microscopy allows the identification of urate crystals (strongly negatively birefringent needle-shaped crystals) and CPPD crystals (weakly positively birefringent rod-shaped or rhomboidal crystals) as shown in Fig. 7.2. The technique is not difficult but the experience of the observer and the adequacy of the microscope (e.g. rotating stage) can make a major difference to accuracy. CPPD crystals are often missed, and thus a repeat examination of a fresh specimen may be appropriate if the diagnosis appears likely, but no crystals are seen initially. Other investigations can provide useful supplementary information but cannot replace synovial fluid examination. X-rays can detect or help to exclude pre-existing joint or bone disorders, chondrocalcinosis (CPPD deposition in cartilage) and bone trauma. It is sensible to assess laboratory parameters of inflammation, such as white cell count and ESR, for comparison with future results but they assist little in the differentiation of septic from gouty arthritis. The serum uric acid level is of little help in the setting of possible acute gout. A normal level does not exclude gout and an elevated level does not confirm gout. However, the uric acid level is very important in the long-term management of gout. 3. interaction between the inflammatory system and the urate crystals (Fig. 7.3).

CRYSTAL ARTHROPATHIES AND THE ANKLE

Differential diagnosis of acute monarthritis of the ankle

Essential anatomy

The ankle joints

Articular capsule, ligaments and tendons

Investigations and diagnosis

Aspiration and synovial fluid analysis

Other investigations

Pathophysiology of gouty arthritis

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

CRYSTAL ARTHROPATHIES AND THE ANKLE

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue