Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the addition of spa therapy to home exercises provides any benefit over exercises and the usual treatment alone in the management of generalised osteoarthritis associated with knee osteoarthritis.

Methods

This study was a post-hoc subgroup analysis of our randomised multicentre trial ( www.clinicaltrial.gov : NCT00348777 ). Participants who met the inclusion criteria of generalized osteoarthritis (Kellgren, American College of Rheumatology, or Dougados criteria) were extracted from the original randomised controlled trial. They had been randomised using Zelen randomisation. The treatment group received 18 days of spa treatment in addition to a home exercise programme. Main outcome was number of patients achieving minimal clinically important improvement at six months (MCII) (≥ −19.9 mm on the VAS pain scale and/or ≥ −9.1 points in a WOMAC function subscale), and no knee surgery. Secondary outcomes included the “patient acceptable symptom state” (PASS) defined as VAS pain ≤ 32.3 mm and/or WOMAC function subscale ≤ 31 points.

Results

From the original 462 participants, 214 patients could be categorized as having generalised osteoarthritis. At sixth month, 182 (88 in control and 94 in SA group) patients, were analysed for the main criteria. MCII was observed more often in the spa group ( n = 52/94 vs. 38/88, P = 0.010). There was no difference for the PASS ( n = 19/88 vs. 26/94, P = 0.343).

Conclusions

This study indicates that spa therapy with home exercises may be superior to home exercise alone in the management of patients with GOA associated with knee OA.

Résumé

Objectif

Voir si l’adjonction d’un traitement thermal aux exercices à la maison et au traitement usuel apporte un bénéfice aux patients souffrant d’arthrose généralisée avec localisation aux genoux.

Méthode

Étude en sous-groupe d’un essai randomisé multicentrique sur la gonarthrose ( www.clinicaltrial.gov : NCT00348777 ). Nous avons étudié uniquement les patients qui remplissaient les critères diagnostique d’arthrose généralisée (Kellgren, American College of Rheumatology ou Dougados). Ils avaient été randomisés selon la méthode de Zelen. Le groupe traité a reçu en plus 18 jours de soins thermaux. Le critère de jugement principal était le nombre de patient avec amélioration cliniquement pertinente de leur état clinique à 6 mois (≥ −19,9 mm sur l’EVA de la douleur et/ou ≥ −9,1 points sur la sous-échelle fonction de l’indice WOMAC) et n’ayant pas subi de chirurgie du genou. Nous avons également étudié divers autres critères de jugement dont le fait que le patient se juge dans un état cliniquement acceptable.

Résultats

Sur 462 patients, 214 avaient une arthrose généralisée. À 6 mois, 182 (88 dans le groupe témoin et 94 dans le groupe cure), ont été analysés pour le critère principal. Une amélioration cliniquement pertinente était plus souvent observée dans le groupe cure ( n = 52/94 vs 38/88, p = 0,010). Il n’y avait pas de différence pour l’état cliniquement acceptable par le patient ( n = 19/88 vs 26/94, p = 0,343).

Conclusions

Cette étude indique que la cure thermale associée aux exercices à la maison pourrait être supérieure aux exercices seuls chez les patients souffrant d’arthrose généralisée avec localisation au genou.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

It has been estimated that the direct cost of OA on the French social security system was 1.6 billions euros ($2.4 billions) in 2002, of which half was for inpatient hospital treatment . The majority of current guidelines for the diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA), which focus on a single articulation e.g. hand, knee, or hip, assume that it is a localised pathology. The term “generalised osteoarthritis” (GOA) was introduced by Kellgren and Moore in 1952, following their observation of 120 patients from which a large majority (85%) presented with Heberden’s nodes . Since the publication of this study, these nodes are considered to be a marker of this illness. Subsequently, several other authors have proposed alternative definitions for GOA, which either include Heberden’s nodes or hand OA or exclude them altogether . However, we showed that according to the classification criteria of Kellgren, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), or Dougados, approximately 50% of the patients recruited for a study focused on knee OA presented with symptoms suggesting GOA . Gunter et al. observed a similar frequency in a population hospitalised for knee or hip arthroplasty . It is appropriate to conclude that localized osteoarthritis and generalized osteoarthritis are two different pathologies.

Bathing in mineral water from natural hot springs has been used in the management of a wide variety of conditions including OA . There is good evidence to show that crenobalneotherapy (also called spa therapy, balneotherapy or crenotherapy) can decrease pain and improve function in persons with knee OA . Many of the 390,000 patients treated each year in the spa centers in France are probably affected by GOA since cross sectional studies indicate that the prevalence of knee, hand and hip OA is 40%, 33% and 28% respectively . Additionally, 70% and 56% of this population report suffering from low back and neck pain respectively . However, no study has been published on the potential benefits of spa treatment for persons with GOA.

Our objective was to evaluate the improvement in clinical symptoms after crenobalneotherapy in a subgroup of patients with GOA. We hypothesise that a combination of home exercises and crenobalneotherapy is superior to home exercises alone.

1.2

Methods

1.2.1

Trial design

The design of this study was a post-hoc analysis of our multicentre 1:1 randomised controlled trial focused on patients with knee OA ( www.clinicaltrial.gov : NCT00348777 ) , which was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration 2000. The original study was carried out in the three largest spa therapy resorts in France, Aix-les-Bains, Balaruc-les-Bains and Dax. In total 29,000, 36,000 and 50,000 people, respectively, attended these three resorts for spa therapy in 2007.

1.2.2

Participants

Patients were recruited between June 2006 and April 2007 from the local areas surrounding the spa centers thus facilitating attendance to treatment sessions on a daily basis. Recruitment was carried out using advertisements in the regional press and posters in pharmacies and general practitioners’ waiting rooms . Advertisements referred to treatment for knee OA but did not specify spa therapy or any other specific treatment modality. Patients were assessed for suitability and enrolled into the study by three trained physicians in private practice outside and independent of the spa settings and had no vested interest in the spa centers. Participants were included in the original study if they had knee OA confirmed by physical examination and the presence of osteophytes on the X-rays . Exclusion criteria were:

- •

knee OA limited to the patellofemoral joint;

- •

severe depression or psychosis;

- •

a contraindication (immune deficiency, evolving cardiovascular conditions, cancer, infection) or intolerance to any aspect of spa treatment;

- •

professional involvement with a spa resort;

- •

spa treatment within the previous 6 months;

- •

intra-joint corticosteroid injection to the knee within the past 3 months;

- •

massage, physiotherapy or acupuncture in the past month; a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) within the past 5 days or other analgesic drug in the previous 12 h, or a change in symptomatic slow-acting drugs prescribed for OA (SYSADOA) in the past 3 months.

For this post-hoc study the participants were retrospectively classified into two groups (GOA and no proof of GOA) according to the following inclusion criteria: pain > 30 mm on visual analogue scale (VAS) with knee OA (ACR criteria ) and a diagnosis of GOA fulfilling the Kellgren criteria (hand OA) and/or the Dougados criteria (hand OA or bilateral knee and spine OA) and/or the ACR criteria (spine OA and two OA localisations). For hand or foot OA, a clinical diagnosis of OA was accepted. For the diagnosis of OA in other localisations e.g. spine, hip, ankle, and wrist, an X-ray examination indicating the presence of osteophytes was required. For this part of the study, diagnostic criteria data for GOA was collected in the “prognostic factors” section of the electronic case report form completed by the physician at initial assessment. In some cases, when the side of the knee OA was not reported by the examining physician, the diagnosis was considered to be unilateral knee OA. Additionally, the localisation of the joint or the level of spine affected by OA had to have been reported.

1.2.3

Randomisation

For all the knee OA patients the randomisation technique of Zelen was used . The Zelen randomisation method implies that patients are not informed of the existence of two different treatment groups. If the patient refused to participate as randomised, he was proposed the other treatment, but remained in their assigned group for intention-to-treat analysis.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to spa therapy or to the control group using a centralised computer programme. Randomisation was stratified by centre and in blocks of 8 with random order. For this post-hoc analysis the patients were kept in their original randomly assigned group. The three examining physicians were trained in the randomisation technique and in how to complete the electronic case report forms (Clininfo, Lyon) under their normal consultation conditions by a clinical research assistant from the coordinating centre, the clinical research centre, Grenoble, France.

Physicians reported the identification of the patients, the inclusion and exclusion criteria before randomisation into the treatment or control groups. Retraining of the examining physicians in the randomisation method was planned if over 15% of patients had changed groups, and the randomisation technique would have been altered if over 30% changed.

1.2.4

Blinding

In order to conceal the existence of the other group and realise a partial blinding of patient , randomisation was performed before written informed consent was obtained. Patients were told only about the group to which they were assigned and given one of the two possible patient information documents with the consent form. In addition, delocalisation of the consultation away from the spa setting was done with the intention of keeping patients ignorant of the other group. Researcher concealment from allocation was assumed by a protected computer file on a website developed for this purpose and used for the randomisation process.

Spa employees were concealed to allocation and partially blinded to the treatment group. Study patients were mixed in with the general population of patients treated in the centre, and the centre personnel were not informed which patients were taking part in the clinical trial.

1.2.5

Interventions

At enrolment, the examining physician orally explained the standardised home exercise programme (HEP) as proposed by O’Reilly and evaluated by Ravaud ( see supplementary material ), to all patients. The importance of performing six repetitions of each of the four exercises, three times daily, was emphasised. All patients from both groups were given a booklet about knee OA including details of the HEP and continued their usual treatments (analgesics, NSAIDS, SYSADOAs, and/or physiotherapy).

Those participants randomised into the spa therapy group received 18 days of therapy over three weeks. The treatments were detailed in a prescription issued by an independent physicians (GP, rheumatologist or physiatrist) attached to the centre (spa physician). Spa mineral water and treatments are approved and controlled by the French authorities. The spa intervention consisted of the following treatments:

- •

general shower of 3 minutes at 38°;

- •

mineral hydro-jet sessions at 37 °C for 15 minutes;

- •

manual massages of the knee and thigh under mineral water at 38 °C by a physiotherapist for ten minutes;

- •

applications of mineral-matured mud at 45 °C for fifteen minutes;

- •

supervised general mobilisation in a collective mineral water pool at 32 °C in groups of six patients for 25 minutes.

The supervised general mobilisation was delivered by a physiotherapist who had been trained in the protocol. This supervised mobilisation programme is not specific to knee OA and also mobilised the spine, shoulders, wrists, hips and ankles. The duration of each treatment was timed by stopwatch and water temperature controlled automatically. The chemical composition of the spa treatment products in each centre was constant. Attendance, tolerance and proper performance of the various treatments was checked during the three visits with the spa physician, at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the 3-week therapy period. In all centres the physiotherapists and hydrotherapists involved in the study were experienced and state registered. Study patients were treated in exactly the same way as non-study patients. The attendance of the patient to all the treatment session was verified by the executives of each spa centre.

Patients in the control group were offered a three-day wellness package at the spa resort following the six-month follow-up visit.

1.2.6

Outcomes

Impact of knee OA on functioning was measured using the Western Ontario and McMasters Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) . A five point Likert scale version of the WOMAC was used for each item, with higher scores indicating greater disability. Pain was measured using the visual analogue scale (VAS) . Quality of life was measured using the validated French version of MOS SF36 (SF36) . The final scores were divided in to two summary measures, the physical component summary score (PCS) and the mental component summary score (MCS). The self-assessments forms were completed by the patients without assistance in the waiting room. Knee flexion, effusion and swelling; associated treatments; patients’ and examining physicians’ overall opinions of outcome (worse, neither worse nor better, better) and adverse events were collected by the same external physicians in each centre who conducted the assessments at baseline and during follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months. At 9 months follow-up the self-assessment forms were completed at home.

The primary outcome for this study was the number of patients achieving Minimal Clinically Important Improvement (MCII) at the sixth month follow-up and no knee surgery. MCII is defined as ≥ −19.9 mm on the VAS pain scale and/or ≥ −9.1 points in a WOMAC function subscale . Secondary outcomes were: MCII at 3 and 9 months, “patient acceptable symptom state” (PASS) defined as VAS pain ≤ 32.3 mm and/or WOMAC function subscale ≤ 31 points and significant improvement in WOMAC and quality of life (SF36) .

1.2.7

Sample size

Using an open preliminary study on 13 usual consecutive patients with knee OA we calculated that 50% could be improved in the spa group and an estimated 25% could improve in the control group. Thus, if the agreed alpha risk is 5% and the beta risk 20%, 58 patients per group or 67 allowing for 15% loss to follow-up was required for this analysis.

1.2.8

Statistical methods

The analysis for the subgroup patients involved an unplanned post-hoc analysis of data from our previous randomised controlled trial . The analysis was based on intention-to-treat principles. We used numbers and frequencies for qualitative variables and averages and standard deviations for continuous variables.

All relevant clinical and demographic variables were tested according to the two a posteriori defined groups. Given that randomisation, considered non-stratified for GOA, cannot guarantee the balance of prognostic factors between the two groups a Chi 2 test was applied once the validity conditions were verified. Otherwise a Fisher’s exact test was applied for qualitative variables, and Student’s t -test was used for continuous variables. Statistical tests were performed with the type I error rate set at α = 0.05.

The primary criterion was tested using a Chi 2 test without continuity correction. We also reported the crude odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Additionally, a multivariate step-down logistic regression to estimate the adjusted OR and the corresponding 95% CI associated with the group to explain the result at six months was performed. A random-effects model was used to account for between-centre differences. The explanatory variables entered into the model were the VAS pain score, the WOMAC pain score, and the WOMAC baseline function score.

Secondary qualitative criteria was also tested by the Chi 2 test without continuity correction: the mean six-month differences in the VAS pain score and the WOMAC function score between the two groups are compared using Student’s t -test. We also calculated the “effect size”. An ANOVA (analysis of variance) for repeated measures was performed to study the physical and psychological dimensions of the SF36 datasheets at baseline and at six months.

The analyses were performed using the STATA software package (version 10.0; Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). The coordination of the study, the monitoring of visits to each centre, data management, data entry, and data analysis were conducted by the Grenoble clinical investigation centre (university of Grenoble, France), which is independent from the evaluated spa centres.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Patients

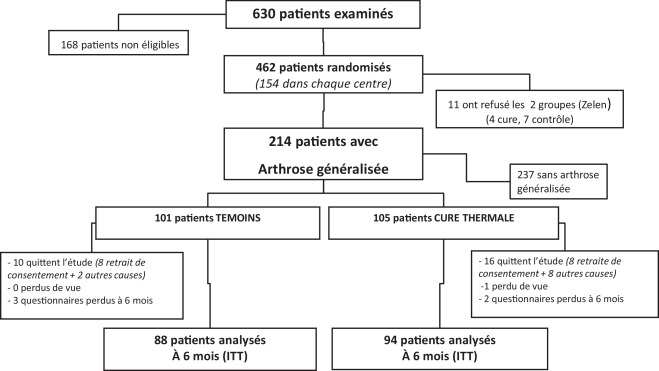

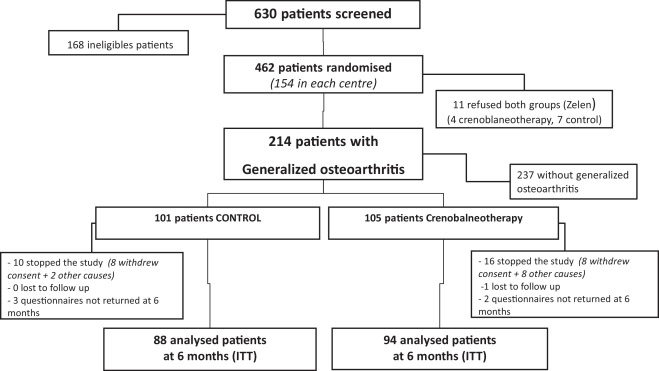

A flow chart of the patient analysis procedure is presented in Fig. 1 . Four hundred and sixty-two patients were recruited into the original study but 11 refused both groups after Zelen randomisation leaving 451 enrolled into the original study. From these 301 directly reported the side of the knee affected by OA on the questionnaire and an additional 98 had swelling and/or crepitation and/or effusion in one or two knees, and so 399 patients were analysed for GOA. The remaining 52 patients were considered to have unilateral knee OA and not included for further analysis. Of the 399 patients assessed for inclusion in this GOA trial, 70 (15.52%) had Heberden’s nodes, 185 (41.02%) had fulfilled the ACR criteria, and 185 (41.02%) displayed the Dougados criteria. In total, 214 (47.45%) patients fulfilling at least one of the three definitions of GOA and were included in the post-hoc analysis. This sample consisted of 101 patients from the original control group and 113 from the spa therapy group. At baseline the groups were similar for all variables except for body mass index (BMI), WOMAC pain score, WOMAC function score, VAS pain, and SF36 PCS ( P < 0.05). Table 1 shows criterion values at baseline.

| Control n = 101 | Crenobalneotherapy n = 113 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male , n (%) | 42 (41.6) | 47 (41.6) |

| Age, mean ± SD ( n ) | 64.8 ± 9.8 | 64.1 ± 9.4 |

| History of treatment for the knee | ||

| Medication, n (%) | 87 (86.1) | 103 (91.2) |

| Massage, n (%) | 35 (34.7) | 38 (33.6) |

| Joint injection, n (%) | 27 (26.7) | 32 (28.3) |

| Hyaluronic acid treatment, n (%) | 44 (43.6) | 48 (42.5) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 35 (34.7) | 41 (36.3) |

| Previous spa therapy, n (%) | 41 (40.6) | 37 (32.7) |

| Other physical treatment, n (%) | 6 (5.9) | 7 (6.2) |

| Prognostic factors | ||

| Length of present episode (months), median (IQR) ( n ) | 36 (12–120) | 48 (12–120) |

| Number of acute episodes, median (IQR) ( n ) | 10 (2–15) | 10 (2–12) |

| Family history of osteoarthritis, n (%) | 58 (57.4) | 66/113 (58.4) |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD ( n ) | 28.9 ± 4.4 a | 31.1 ± 5.9 a |

| Knee examination | ||

| Knee joint swelling, n (%) | 56 (55.4) | 61 (54.0) |

| Knee joint effusion, n (%) | 27 (26.7) | 31 (27.4) |

| Knee joint crepitation on active motion, n (%) | 49 (48.5) | 48 (42.5) |

| Radiological severity Kellgren and Lawrence n (%) | ||

| Grade 1 | 38 (37.6%) | 38 (33.6%) |

| Grade 2 | 24 (23.8%) | 31 (27.4%) |

| Grade 3 | 31 (30.7%) | 37 (32.7%) |

| Grade 4 | 8 (7.9%) | 7 (6.2%) |

| WOMAC pain score (0–100) mean ± SD ( n ) | 43.2 ± 18.1 a | 48.3 ± 17.8 (112) a |

| WOMAC function score (0–100), mean ± SD ( n ) | 42.2 ± 16.2 (99) a | 47.4 ± 20.3 (108) a |

| VAS pain (0–100 mm), mean ± SD ( n ) | 47.1 ± 16.8 a | 54.2 ± 19.4 (112) a |

| Patient acceptable symptom state , n (%) | 7 (6.9) | 6/112 (5.4) |

| SF36 scores | ||

| PCS, mean ± SD ( n ) | 37.7 ± 6.9 (97) a | 35.5 ± 7.2 (108) a |

| MCS, mean ± SD ( n ) | 45.2 ± 10.8 (97) | 45.9 ± 11.6 (108) |

| Medication (at the time of inclusion) | ||

| At least one medication, n (%) | 54 (53.5) | 64 (56.6) |

| NSAID, n (%) | 15 (14.9) | 18 (15.9) |

| SYSADOA n (%) | 24 (23.8) | 24 (21.2) |

| Analgesic, n (%) | 33 (32.7) | 43 (38.1) |

| Hyaluronic acid, n (%) | – | 1 (0.9) |

1.3.2

Outcomes

Minimally clinically important improvement was observed more often ( P = 0.010) in the spa group (52/94; 55.3%) than in the control group (32/88; 36.4%). No surgery was performed in these patients. The adjusted odds ratio was 1.99 ([1.06–3.77]; P = 0.033) after the adjustment of the three outcomes with significant differences at baseline (WOMAC pain, WOMAC function, and pain) and the step-down model; the NNT is 5.3. The results for the main outcomes and MCII are presented in Table 2 . Secondary outcomes are reported in Table 3 .

| Outcome | Control | Spa treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimally clinical important improvement | |||

| 6 months | 36% (32/88) | 55% (52/94) | 0.010 |

| OR unadjusted [CI 95%] | 2.17 [1.20–3.93] | 0.011 | |

| OR adjusted a [CI 95%] | 1.99 [1.06–3.77] | 0.033 | |

| Minimally clinical important improvement b | |||

| 3rd month | 37% (31/84) | 62% (53/86) | 0.001 |

| 6th month pain | 18% (16/88) | 36% (33/92) | 0.008 |

| 6th month WOMAC function | 31% (25/81) | 45% (39/87) | 0.063 |

| 9th month | 35% (27/77) | 57% (47/82) | 0.005 |

a Adjusted for WOMAC pain, WOMAC function, and VAS at baseline.

b MCII is defined as ≥ 19.9 mm on the VAS pain scale and/or ≥ 9.1 points on the WOMAC function subscale normalised to a 0–100 score.

| Outcome | Control | Spa treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s acceptable symptom state | |||

| 3rd month | 21% (18/84) | 26% (22/86) | 0.523 |

| 6th month | 22% (19/88) | 28% (26/94) | 0.343 |

| 9th month | 30% (23/77) | 32% (26/82) | 0.802 |

| Evaluation of pain at 6th month | −3.5 ± 23 ( n = 88) | −11.7 ± 26 ( n = 92) | 0.029 |

| Standardised response mean for pain | 0.21 [−0.08–0.51] | 0.59 [0.30–0.88] | |

| Evaluation of WOMAC at 6th month | −4.1 ± 16 ( n = 81) | −8.7 ± 16 ( n = 87) | 0.062 |

| Standardised response mean for WOMAC | 0.24 [−0.07–0.55] | 0.43 [0.13–0.73] | |

| Opinion of patient at 6th month | n = 83 | n = 87 | 0.009 |

| Worsen | 13% (11) | 7% (6) | |

| Unchanged | 57% (47) | 40% (35) | |

| Improved | 30% (25) | 53% (46) | |

| Opinion of practitioner at 6th month | n = 83 | n = 87 | 0.035 |

| Worsen | 7% (6) | 5% (4) | |

| Unchanged | 63% (52) | 46% (40) | |

| Improved | 30% (25) | 49% (43) | |

| Treatments at 6th month | n = 83 | n = 87 | |

| NSAID | 7.2% (6) | 16.1% (14) | 0.073 |

| SYSADOA | 20.5% (17) | 17.2% (15) | 0.589 |

| Painkiller | 7.2% (6) | 21.8% (19) | 0.007 |

| Hyaluronic acid injection | 7.2% (6) | 2.3% (2) | 0.161 |

| SF36 physical at 6th month | 39.7 ± 7.7 ( n = 83) | 39.0 ± 9.4 ( n = 87) | 0.453 |

| SF36 psychic at 6th month | 47.9 ± 9.5 ( n = 83) | 46.2 ± 11.5 ( n = 87) | 0.137 |

For each criterion, we tested the interaction between the group and GOA. No significant results were obtained. For the primary criterion, the rate of patients with MCII at six months was 36.4% in the control group vs. 55.3% in the treated group for patients with GOA. For patients without GOA, the rate was 36.4% in the control group vs. 46.5% in the treated group (no significant interaction; P = 0.400).

1.3.3

Harms

Several side effects were reported from the spa therapy group, venous insufficiency (1), acute low back pain (2), erysipelas (1), asthenia (1), and joint effusion (1). No side effects were recorded in the control group.

1.4

Discussion

Our data seems in favour of spa therapy for patients with GOA. This post-hoc subgroup analysis of a randomised study indicate that spa therapy in combination with a home exercise programme may provide better clinically relevant improvement in pain and knee function in comparison with a home exercise programme alone in patients suffering from GOA. However, the improvements in patient acceptable symptom state or quality of life were not sufficient to reach a significant improvement.

We acknowledge that this subgroups analysis does not fulfil all the criteria for subgroup analysis as described by Sun et al. . However, these were developed to prevent the development of false-positive results by chance when the original study results are negative whereas our original study reported a positive effect. In addition, we discovered that most of the patient had no knee OA but GOA after the conclusion of the study, so it was not possible to plan this analysis in the protocol. Further, we believe that the publication of this subgroup analysis is justified by the fact that the localized knee osteoarthritis and generalized osteoarthritis are two different pathologies.

To our knowledge this is the first published clinical study evaluating the effects of spa therapy on symptoms related to GOA. In addition to the proven benefits of crenobalneotherapy in the management of knee OA, several trials shows evidence of moderate beneficial effects for low back pain and hand osteoarthritis , which are considered as the other main localisations of GOA . Although several components of crenobalneotherapy, such as massage application, were focused only on the knee joint, all of the other painful localisations were affected by the remaining components of the spa therapy (mud pack, bath, shower, and supervised water exercises in the therapy pool), indicating the potential benefit of spa therapy on multiple localisations of OA which has been shown in the results of this study.

The main limitation is the consequence of the between group difference at baseline which may have overestimated the number of improved patients in the crenobalneotherapy group because the more severe clinical conditions can lead to a more regression to the mean. However, we must point out that this difference does not explain the fact that the clinical condition of patients is better in this group after treatment and at follow-up.

This study has several other strengths and limitations. As there is no consensus on the definition of GOA , we decided to combine three complementary classification criteria for GOA and this could have caused an over estimation on the number of patients classified with GOA. However, we felt this was a reasonable method for classification based on the findings of our previous study . As an unplanned post-hoc subgroup analysis, the positive results may have been purely a result of chance. To reduce this possibility, we carried out the identical analysis as planned in our original registered clinical trial for all patients with or without GOA. The lack of blinding of patient is known to promote the “placebo” effect. In this study, this effect is minimised by utilisation of the same follow-up method for both groups and the MCII as a qualitative endpoint. Qualitative endpoints have been found to give non-significant results in a meta-analysis comparing placebo with no treatment . More recently, the same author showed that the lack of blinding of assessment in binary outcomes provides a low rate of misclassification (3% [1–7%]) compared with the blinded assessment . The utilisation of the Zelen randomisation method and the proposition of a home exercise programme may reduce the deception bias in the control group that overestimate the between group difference. The WOMAC index has been validated for knee OA and is applicable to hip OA and can be partly relevant in spinal OA. It is not suitable for the measurement of the clinical consequences of hand OA and therefore using the WOMAC result for GOA may not have been sensitive enough.

With methodological limitations, this study indicates that spa therapy with home exercises may be superior to home exercise alone in the management of patients with GOA associated with knee OA. A consensus remains lacking on the definition of GOA preventing specific evaluation, with clinical trials, of treatment efficacy therefore, an agreed definition of GOA is required. Further, high quality randomised trials are necessary to confirm the results of this preliminary study.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Contribution

R. Forestier wrote the protocol, contributed to collect data and wrote the article.

C. Genty performed the statistical analysis and contributed to write the article.

B. Waller contributed to translate and to write the article.

A. Françon contributed to write the protocol, to collect data and to write the article.

H. Desfours contributed to collect data and to write the article.

C. Rolland contributed to write the protocol, supervised the data management and contributed to write the article.

C.F. Roques contributed to write the article.

J.L. Bosson contributed to write the protocol and contributed to write the article.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandrine Massicot for data monitoring. We also thank the examining physicians: Drs Y. Attal, J.-C. Perronnard and L. Mendiharrat; the spa physicians and the secretaries in each centre, and the Osteoarthritis group of the French Society for Rheumatology for their support and contribution to the protocol (in particular Pr Eric Vignon, Dr Michel Lequesne, Prs Serge Poiraudeau, Prs Jean-François Maillefert and and Xavier Chevalier).

Participating physicians working with the spas

Aix-les-Bains: Drs Bernard, Forestier, Françon, Gerrud, Guillemot, Joly, Palmer, Souchon.

Balaruc-les-Bains: Drs Ballini-Cammal, Calas-Vedel, Cammas, Cassanas, Cros, Desfours, Rivalland-Lentz, Rousseau, Tuffery, Vidil-Roux.

Dax: Drs Doppia, Karrasch, J Lavielle, V Lavielle, Fretille, Grillon, Lacoste, Pale, Boniol-Maurel, Labaste, Guchan, Le Poncin, Delest, Soullard, Legros, Reau-Legros, Maligne, Petit, Chicoye, Prothery.

Funding

This study was funded by:

- •

the French Society for Spa research (Association française pour la recherche thermale [AFRETH]) a non-profit organisation;

- •

the Rhone-Alpes regional council;

- •

the County Council of Savoie.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

On estime que les coûts directs de l’arthrose pour la sécurité sociale ont été de l’ordre de 1,6 milliards d’euros en 2002, dont environ la moitié était consacrée à financer les hospitalisations . La majorité des recommandations existantes se focalisent sur une articulation comme la main, le genou ou la hanche, sous-entendant qu’il s’agit d’une pathologie locale. Le terme d’arthrose généralisée a été introduit par Kellgren et Moore en 1952, après la description d’une série de 120 patients dont 85 % présentaient des nodosités d’Heberden . Depuis cette publication, ces nodosités sont considérées comme un marqueur de l’arthrose généralisée. Par la suite, d’autres auteurs ont proposé des définitions alternatives pour l’arthrose généralisée, incluant ou non la présence de nodosités d’Heberden ou d’arthrose de la main. Dans une publication récente nous avons montré que 50 % des patients inclus dans un essai randomisé sur la gonarthrose présentaient une arthrose généralisée selon les critères de Dougados, de l’American College of Rheumatology (ACR) ou de Kellgren . Günter et al. ont observé une fréquence similaire dans une population hospitalisée pour prothèse de hanche ou de genou . Il est probable que l’arthrose localisée et l’arthrose généralisée sont deux pathologies différentes.

Les bains dans l’eau thermale sont utilisés dans le traitement de nombreuses pathologies et principalement l’arthrose . Il y a un bon niveau de preuve pour montrer que la crénobalnéothérapie (également appelée cure thermale, ou balneotherapy pour les Anglo-Saxons) peut améliorer les douleurs et améliorer les capacités fonctionnelles des patients souffrant de gonarthrose . La plupart des 390 000 patients faisant une cure rhumatologique en France présentent probablement une arthrose généralisée comme le montre une étude transversale qui observait une prévalence élevée de la gonarthrose, de la coxarthrose et de l’arthrose de la main (40 %, 33 % et 28 % respectivement) . De surcroît, 70 % des patients cette population déclarait souffrir également de lombalgies et 56 % de cervicalgies . Pourtant, aucune étude n’a encore été publiée sur les bénéfices potentiels de la cure thermale dans l’arthrose généralisée.

L’objectif de ce travail est d’observer l’évolution clinique des patients après une cure thermale dans un sous-groupe de patients ayant une gonarthrose et une arthrose généralisée. Nous formuons l’hypothèse qu’une combinaison de soins thermaux et d’exercices à domicile est supérieure aux exercices seuls.

2.2

Méthode

2.2.1

Design de l’essai

Il s’agit d’une étude en sous-groupe constitué a posteriori d’un essai randomisé 1:1 multicentrique, réalisé sur des patients présentant une gonarthrose ( www.clinicaltrial.gov : NCT00348777 ) . Il a été réalisé en accord avec la déclaration d’Helsinki en 2000. L’étude princeps a été réalisée dans les 3 plus grands centres thermaux français : Aix-les-Bains, Balaruc-les-Bains et Dax qui ont accueilli respectivement 29 000, 36 000 et 50 000 patients, en 2007.

2.2.2

Participants

Les patients ont été recrutés entre juin 2006 et avril 2007 dans un rayon de 30 km autour des 3 stations pour permettre aux patients de se rendre quotidiennement au centre thermal par leurs propres moyens.

Le recrutement s’est fait par annonce dans la presse locale et régionale, des affiches dans les pharmacies et les salles d’attente des praticiens de la région proche . Les affiches faisaient référence à un traitement de l’arthrose du genou mais n’évoquaient pas la cure thermale ni aucune autre modalité thérapeutique. Les patients étaient examinés pour éligibilité et recrutés dans l’étude par 3 praticiens de ville expérimentés indépendants des centres thermaux et qui n’avaient aucun intérêt dans le fonctionnement de ces centres thermaux. Les participants étaient inclus dans l’étude, s’ils avaient une arthrose du genou confirmée par l’examen clinique et par la présence d’ostéophytes à la radiographie standard . Les critères d’exclusion étaient :

- •

la présence d’une arthrose limitée au compartiment fémoro-patellaire ;

- •

une dépression sévère ou une psychose ;

- •

une contre-indication à la cure (déficit immunitaire, pathologie cardiovasculaire évolutive, cancer évolutif, infection) ou intolérance à un aspect du traitement thermal ;

- •

intérêts personnels ou professionnels dans le thermalisme ;

- •

cure thermale dans les 6 mois précédents ;

- •

injection de corticoïdes dans le genou moins de 3 mois avant ;

- •

massages, physiothérapie ou acupuncture dans le mois précédent, prise d’anti-inflammatoires modifiée depuis moins de 5 jours ou traitement antalgique modifié dans les 12 dernières heures ou changement dans un traitement antiarthrosique d’action lente dans les 3 derniers mois.

Pour cette étude en sous-groupe a posteriori les participants ont été rétrospectivement classifiés en 2 groupes (arthrose généralisée ou absence de preuve d’arthrose généralisée) selon qu’ils présentaient ou non les critères d’inclusion suivants : douleur > à 30 mm sur l’échelle visuelle analogique de la douleur (EVA) avec une arthrose 2 genoux selon les critères de l’ACR et diagnostique d’arthrose généralisée selon les critères de Kellgren (arthrose des mains), de Dougados (arthrose des mains ou association d’arthrose du rachis et des 2 genoux) ou de l’ACR (arthrose du rachis et au moins 2 autre localisations d’arthrose). Pour l’arthrose de la main et du pied un diagnostic clinique était accepté. Pour le diagnostic des autres localisations d’arthrose (rachis, hanche, chevilles et poignet) la présence d’ostéophytes à la radiographie standard était requise. Pour cette partie de l’étude, les critères diagnostiques étaient recueillis dans la partie facteur pronostique de la grille de saisie informatique par le médecin examinateur, lors de l’examen initial. Dans certains cas, lorsque le côté de l’arthrose du genou n’était pas précisé par le médecin examinateur, le diagnostic était considéré comme une arthrose unilatérale.

2.2.3

Randomisation

Pour les patients de l’étude une randomisation selon la méthode de Zelen a été utilisée . La méthode de Zelen implique que le patient ne soit pas informé de l’existence de 2 groupes de randomisation. Si un patient refuse de participer dans le groupe où il a été randomisé, on lui propose l’autre traitement, mais il est analysé dans le groupe initial lors de l’analyse en intention de traiter.

Les patients éligibles ont été randomisés dans le groupe cure thermale ou le groupe témoin par un programme de randomisations centralisée. La randomisation été stratifiée par centre et par blocs de 8 dans un ordre aléatoire. Pour cette analyse en sous-groupe, les patients ont été conservés dans leur groupe de randomisations initiales. Les 3 médecins examinateur ont été entraînés à la technique de randomisations et à la méthode de remplissage du formulaire de saisie informatisé (Clininfo, Lyon) dans leurs conditions de consultation habituelles par un assistant de recherche clinique du centre de coordination, le centre d’investigation clinique du CHU de Grenoble, France.

Les praticiens devaient inscrire l’identité du patient, les critères d’inclusion et d’exclusion avant de pouvoir recevoir le résultat de la randomisation entre le groupe cure thermal et le groupe exercices à domicile. Un réentraînement des praticiens à la méthode de randomisation était planifiée si plus de 15 % des patients changeaient de groupe et il avait été considéré que la randomisation de Zelen serait remise en cause si plus de 30 % des patients changeaient de groupe.

2.2.4

Insu

Dans le but de dissimuler l’existence de l’autre groupe et de réaliser un insu partiel des patients , la randomisation a été réalisée avant le consentement éclairé. Les patients recevaient une information qui ne concernait que le groupe dans lequel ils avaient été randomisés. L’examen des patients était réalisé dans le cabinet du médecin examinateur, à distance du centre thermal de façon que ceux qui ne recevaient pas le traitement thermal ne soit pas informés de l’existence de celui-ci. Le médecin examinateur ne pouvait prévoir le groupe dans lequel le patient serait randomisé grâce au programme informatique développé sur le site Internet de l’étude et qui le tenait à l’écart du processus de randomisation.

Les employés des centres thermaux n’étaient pas informés de quels patients participaient à l’étude. Les patients étaient mélangés aux patients habituels de la station et ils étaient chargés de ne pas révéler leur participation à l’étude.

2.2.5

Traitements

À l’inclusion, le médecin examinateur expliquait oralement le programme d’exercices à domicile tel qu’il a été proposé par O’Reilly et évalué par Ravaud ( voir matériel supplémentaire ), à tous les patients. L’importance de répéter à 6 reprises chacun des 4 exercices 3 fois par semaine était rappelée à chaque visite. Chacun des patients des 2 groupes recevait également un livret d’information sur l’arthrose reprenant en détails les exercices à domicile. Ils étaient autorisés à continuer leur traitement habituel (antalgiques, anti-inflammatoires, antiarthrosiques d’action lente et ou physiothérapie).

Les participants randomisés dans le groupe crénobalnéothérapie recevaient en plus 18 jours de traitement thermal en 3 semaines. Ces traitement étaient prescrits et surveillés par un médecin thermal indépendant du centre thermal (médecin généraliste, rhumatologue ou médecin de rééducation fonctionnelle). L’eau thermale et les procédures thérapeutiques sont approuvées et contrôlées par les autorités sanitaires françaises. Le traitement thermal comportait les techniques suivantes :

- •

douches générales de 3 minutes à 38° ;

- •

hydrothérapie à 37° pendant 15 minutes ;

- •

massages manuels du genou et des structures adjacentes sous affusions d’eau minérale à 38° pendant 10 minutes par un physiothérapeute ou un kinésithérapeute diplômé et expérimenté ;

- •

applications de boue minérale naturelle dans l’eau thermale à 45° pendant 15 minutes ;

- •

mobilisation supervisée en piscine thermale à 32° par groupe de 6–8 patients pendant 25 minutes.

Les mouvements étaient supervisés par un physiothérapeute ou un kinésithérapeute entraîné au protocole et expérimenté. Ce programme de mobilisation n’est pas spécifique de l’arthrose du genou et mobilise également le rachis, les épaules, les poignets, les hanches et les chevilles. La durée des différentes techniques thermales était contrôlée par une minuterie et la température de l’eau contrôlée automatiquement. La composition chimique de l’eau thermale est par définition stable au cours du temps (il s’agit d’une des conditions incontournables de reconnaissance d’une eau minérale thermale par l’académie de médecine). La bonne tolérance aux soins et leur bon déroulement était vérifié à 3 reprises pendant la cure par un médecin thermal. Dans tous les centres, les kinésithérapeutes sont diplômés et expérimentés. Les patients de l’étude étaient traités exactement comme les autres curistes de la station. La présence des patients dans les services de soin était vérifiée chaque jour par les cadres de l’établissement comme on le fait pour les curistes habituels.

Les patients du groupe témoin ont reçu 3 jours de 3 soins dans le secteur remise en forme de l’établissement à la fin de l’étude.

2.2.6

Critères de jugement

L’impact de la gonarthrose sur les capacités fonctionnelles des patients a été mesuré par l’indice Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) dont les scores les plus élevé indiquent un retentissement fonctionnel plus important. Nous avons utilisé la version avec l’échelle de Lickert en 5 points. La douleur a été mesurée par l’échelle visuelle analogique (EVA) de la douleur de Huskinsson . La qualité de vie a été mesurée par une version française du MOS SF36 (SF36) . Le score final de ce questionnaire est agrégé en deux sous dimensions physique et psychique. Les auto-questionnaires sont complétés par les patients en dehors de la présence du médecin. La flexion du genou, la présence d’un épanchement et d’un gonflement articulaires et l’opinion du médecin examinateur sont remplis par le même médecin examinateur à l’inclusion et au moment des visites de suivi. Les questionnaires à 9 mois sont complétés à domicile.

Le critère de jugement principal de cette étude est le nombre de patient présentant une amélioration cliniquement pertinente et l’absence de chirurgie du genou à 6 mois. L’amélioration cliniquement pertinente est un critère validé, défini comme une amélioration d’au moins 19,9 mm sur l’EVA de la douleur et/ou de 9 points sur l’échelle WOMAC fonction . Les critères secondaires sont le sentiment par le patient d’atteindre un état cliniquement acceptable, critère validé défini comme une EVA de la douleur inférieure ou égale à 32,2 mm et/ou une échelle WOMAC fonction ≤ 31 points .

2.2.7

Taille de l’étude

Sur la base d’une étude préliminaire ouverte avec 13 patients consécutifs, nous avons observé que 50 % des patients avaient une amélioration cliniquement pertinente et nous estimions que 25 % des patients du groupe témoin pourraient être améliorés. Avec un risque alpha de 5 % et un risque bêta de 20 % il faudrait 58 patients par groupe (67 patients par groupe si on prend en compte la possibilité de 15 % de perdus de vue).

2.2.8

Méthodes statistiques

Cette analyse en sous-groupe n’était pas prévue dans le protocole de notre essai randomisé initial . Elle a été menée en intention de traiter.

L’analyse descriptive porte sur les principales variables recueillies. Nous utilisons les nombres et fréquences pour les variables qualitatives, et les moyennes et écart-types pour les variables continues.

Un tableau montrant la description initiale des deux groupes est présenté avec l’ensemble des variables démographiques ou cliniques pertinentes, ainsi que les tests statistiques correspondants, puisque les deux groupes ne sont pas randomisés dans cette sous population de patients avec polyarthrose (test du Chi 2 si les conditions de validité sont vérifiées, ou sinon test exact de Fisher pour les variables qualitatives et test de Student pour les variables continues). En cas de non-respect de la loi normale pour les variables continues, nous avons plutôt choisi de présenter les médianes et IQR ( inter-quartile range : 25 e et 75 e percentiles) avec comme test de comparaison le test de Mann-Whitney.

Les tests statistiques ont été effectués avec le risque d’erreur de première espèce usuel p = 0,05.

Le critère principal est testé à l’aide d’un test du Chi 2 sans correction de continuité. Nous donnons également l’ odds ratio (OR) brut et l’intervalle de confiance (IC) à 95 % correspondant. Nous avons également effectué une régression logistique multivariée pour estimer l’OR ajusté et l’IC à 95 % correspondant, associé au groupe pour expliquer le succès à 6 mois. Un modèle à effet aléatoire a été utilisé pour prendre en compte l’effet centre. Les variables explicatives entrées dans le modèle sont l’EVA douleur, le WOMAC douleur et le WOMAC fonction à l’inclusion.

Les critères secondaires qualitatifs sont également testés par le test du Chi 2 sans correction de continuité ; la comparaison de la différence moyenne 6 mois – inclusion de l’EVA douleur et du WOMAC fonction entre les 2 groupes est effectuée par le test de Student. Nous présentons également l’ effect size .

Les analyses ont utilisé le logiciel STATA (version 10.0 ; Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). La coordination de l’étude, le monitoring des visites dans chaque centre, le data management, la saisie des données et l’analyse des données a été réalisée par le centre d’investigation clinique de Grenoble (université de Grenoble, France) qui est un centre universitaire indépendant des centres thermaux.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Patients

Un diagramme de flux de l’analyse des patients est présenté sur la Fig. 1 . Quatre cent soixante-deux patients ont été recrutés dans l’étude originale et 11 d’entre eux ont refusé les deux groupes après la randomisation, laissant 451 patients dans l’étude. Trois cent un d’entre eux précisaient le côté de l’atteinte du genou et 98 autres présentaient un gonflement du genou, un crépitement ou un épanchement. De ce fait, l’application des critères d’arthrose généralisée a été réalisée sur 399 patients. Les 52 patients restants ont été considérés comme une gonarthrose unilatérale et exclus de l’analyse. Sur ces 399 patients, 70 (15,52 %) avaient des nodosités d’Heberden, 185 (41,02 %) répondaient aux critères de l’ACR et 185 (41,02 %) aux critères de Dougados. Au total, 214 (47,45 %) patients répondaient à au moins une des définitions d’arthrose généralisée et ont fait l’objet de cet article. Cent un étaient dans le groupe témoin et 113 dans le groupe thermal. À l’inclusion, les deux groupes étaient similaires pour toutes les variables pronostiques sauf pour l’indice de masse corporelle, les sous-échelles douleur et fonction du WOMAC, l’EVA de la douleur et la dimension physique du SF36 ( p < 0,05). Le Tableau 1 montre ces valeurs à l’inclusion.