Corrective Osteotomy for Radius and Ulna Diaphyseal Malunions

Vimala Ramachandran

Thomas F. Varecka

DEFINITION

Malunion of the radial or ulnar shaft can lead to pain, loss of motion, loss of strength, and instability at the level of the wrist or elbow.

Malrotation, angulation (with narrowing of the interosseous space between the radius and ulna), shortening, and loss of the radial bow have been shown in various studies to lead to decreased functional outcomes.4, 5, 9, 10, 12

Arthritis has been reported at the level of the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) with long-standing malunions, although the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) is most commonly affected by forearm malunions.11

ANATOMY

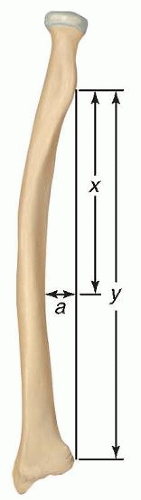

The forearm can be thought of as a ring, connected at the PRUJ, the interosseous membrane, and the DRUJ (FIG 1).

Force transmission occurs through the interosseous membrane from the radius distally to the ulna proximally.

Radius

The radius lies parallel to the ulna in supination. With pronation, it rotates around the ulna while the ulna maintains its position throughout forearm rotation.

The radius shaft is triangular in cross-section, with the apex toward the attachment of the interosseous membrane.

It contains three surfaces: anterior, lateral, and posterior.

The shaft possesses a gentle bow, with the volar surface concave and the dorsal and lateral surfaces convex.1

Ulna1

The ulna is a long bone that has a triangular cross-section in the proximal two-thirds and a circular cross-section distally.

It possesses three surfaces: anterior, posterior, and medial.

The proximal half of the shaft is slightly concave volarly. The distal half is relatively straight.

The PRUJ consists of the radial head, the radial notch, the annular ligament, and the quadrate ligament.

The DRUJ consists of the sigmoid notch, the ulnar head, the dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments, the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) subsheath, and the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC).

PATHOGENESIS

Both-bone forearm fractures occur through a variety of mechanisms, including indirect trauma (such as falls on an outstretched arm or motor vehicle accidents) and direct trauma (such as blows to the forearm).

Acute fractures treated closed or with intramedullary nailing techniques are more likely to heal malunited.7, 8

A torsional deformity of greater than 30 degrees in the radius leads to significant loss of forearm motion.4

Changes in the length-tension curve of the interosseous membrane may also account for loss of rotation.12

NATURAL HISTORY

Fifty degrees of supination and 50 degrees of pronation are needed for activities of daily living.6

Patients with untreated forearm malunions may experience loss of forearm rotation, PRUJ or DRUJ instability, wrist pain, loss of strength, and arthritis at the PRUJ.11 The severity of the symptoms depends on the degree of malunion and the corresponding alteration in degree and location of the bow of the radius.

Malunions of 10 degrees or less lead to less than a 20-degree loss of forearm rotation and hence are clinically insignificant.7

Patients with greater than 15 degrees of malalignment or loss of the radial bow will have clinically significant loss of motion and strength if left untreated.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The preoperative evaluation for patients with forearm malunions includes a detailed assessment of the patient’s functional limitations as well as documentation of elbow and wrist range of motion, the supination-pronation arc of the forearm, and the stability of the PRUJ and DRUJ.

Physical examination

The skin is inspected for scarring or previous incision sites.

Muscle bulk and tone are examined.

The wrist, elbow, and malunion site are palpated for tenderness.

Range of motion

The flexion-extension arc of the elbow is measured with the shoulder at 30 degrees of forward flexion.

Rotation of the forearm is ascertained with the humerus stabilized against the chest wall and the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion.

Wrist flexion and extension are determined with the forearm in neutral rotation.

Joint loss of motion may indicate location of pathology.

A high degree of motion loss will lead to functional deficits.

PRUJ and DRUJ

Stability of the PRUJ is assessed by palpation during passive pronation and supination.

The DRUJ is evaluated by stressing the ulna volarly and dorsally while stabilizing the radius.

Subluxation of the ulnar head or the ECU is evaluated during passive range of motion (ECU subluxation test).

The piano key test can also be used to assess for an unstable DRUJ. Patients with a positive piano key sign will have an ulnar head that shifts volarly with a minimal volarly directed force and then rebounds dorsally once that force is removed, much like a key in a piano.

Pain with compression of the radius and ulna at the level of the DRUJ may also be indicative of DRUJ instability or arthritis (DRUJ compression test).

Neurovascular examination

The examiner should check for anterior interosseous nerve (OK sign), posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) (thumb extension), and ulnar nerve (abduction-adduction of fingers) function.

Inability to perform tasks identifies nerve injury.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of both forearms should be obtained (FIG 3A,B).

Both the bicipital tuberosity and the radial styloid should be visualized for the film to be adequate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree