Compensatory and social justice: societal sources of claims for health care

Objectives

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

compensatory justice

stigma

workman’s compensation

collective responsibility

communitarian approach

interdependence

altruism

reciprocity ethic

social need

labeling

“the dilemma of difference”

vulnerability

social marginalization

solidarity

personal responsibility for health

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Nonmaleficence | 4 |

| Distributive justice | 15 |

| Social justice | 15 |

| Equity | 15 |

Introduction

Justice issues often are difficult to grasp because they require professionals to move beyond their usual one-on-one interaction to consider the well-being of whole groups of people. As you learned in the previous chapter, distributive justice focuses on medical conditions as the basic approach to justly allocating resources. This chapter introduces two other related dimensions of justice that are pertinent in some of the situations you will face as a health professional. Compensatory justice and social justice (introduced in Chapter 15) both arise from the observation that not everyone has the same chance as others to benefit from basic societal services and goods. The similarity between the two types of justice is that each takes into account additional factors to medical conditions, those factors being related to the person’s or group’s relatively disadvantaged position in society. Compensatory justice has built into it an assumption that the person or group at least has a role (e.g., worker) that is valued by mainstream society. In contrast, social justice is a “no fault” position that says regardless of social role it is simply the societal disadvantage that matters. The assumption is that a well-working society has to respect everyone where they are and try to make adjustments regarding who needs what. At the core of the issue for our study here is the concern that some groups of people have health problems related to their disadvantaged position in the larger society. We devote most of the study in this chapter to compensatory justice but also demonstrate how it is one aspect of the broader concept of social justice, the latter of which focuses on serious disparities in health and health care allocations.

The story of the Maki brothers is an example designed to help you focus on how social contexts factor into compensatory justice considerations and how you, the health professional, are involved.

The story of John and Eino Maki raises numerous ethical questions. For instance, some people reading this story have questions about confidentiality. Why is Kai Nielson sharing all of this potent information with John when Eino, a competent adult, is the patient? What about Eino’s informed consent? Is it appropriate for the physician to put the burden of sharing the bad news with Eino on John’s shoulders? What should the role of the physician assistant and social worker be? These are certainly important ethical questions. However, we beam our lens in this chapter on the justice issues that patients in similar situations to Eino’s raise. Their basic similarity is that they are among the members of society who are dismissed or even disdained by members of mainstream society even though they contribute in ways that society needs for its overall well-being.1

The goal: a caring response

Eino Maki, a seemingly healthy, hard-working man, becomes a victim of circumstances that leave his health compromised. A caring response by health professionals requires that they do whatever is “best” or, in the language of ethics, is beneficent for this patient. In the story, the physician assistant and Kai Nielson have been doing exactly that in their attempt to get at the clinical root of Eino’s symptoms, and they each make strong recommendations about what he needs to do. At the same time, they know that matters are fast slipping out of their hands. There is an environmental source of his cancer, a death-dealing cancer we presume, triggered by his employment in a company where he likely has been exposed to toxic levels of asbestos over a prolonged period of time. Mr. Maki’s decision about what to do for his cancer treatment will depend in part on the availability of funds from his employing company or a government source to help pay for them. If the professionals think this through to its logical conclusion, they will realize that a caring response requires that they try to help build and strengthen institutions and societal arrangements that support individuals in such predicaments. Involvement at this level is aimed at policies that reflect justice for groups of people who are societally disadvantaged. The “Eino Makis” do not have the same opportunity to choose among desirable job options to the extent that persons who are better situated financially and socially do. Such policies are not designed only for one person (e.g., Mr. Maki) the way a treatment plan is created for a specific patient but outline a program that covers him and others like him. There is a subgroup of institutional and social arrangements that address legal mechanisms to compensate persons for harms incurred in the larger environment whether workplace, home, or publicly shared spaces. Compensatory justice deals with this reality from an ethical and legal standpoint, and it is the ethical considerations we consider here.

The six-step process in compensatory justice decisions

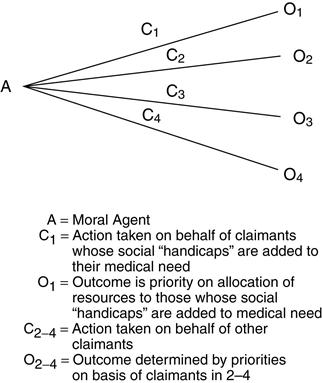

In Chapter 15, you studied about allocation dilemmas when whole groups of individuals become eligible for goods or services because of their medical need.

Now the lens of justice turns to include an additional question. What ethical difference does it make when a patient’s medical need is caused by injury or illness but this person’s condition is also caused by his societal position and the lifestyle people in that position have? Eino Maki is one excellent example. He is carrying out a type of work that is dangerous to his health but remains in a job available to him and others who have similar low social and economic status in society. You might respond that others who are at more financially secure levels of society have an opportunity for this kind of work too. True, but this reasoning is akin to the French political philosopher during the French Revolution who observed that “both the rich and the poor have an equal right to sleep under the bridges of Paris at night.” Eino’s autonomy to select a safer or more pleasant work environment is greatly diminished or absent.

Thoughtful individuals have pondered the role that such societally determined differences among patients should play. To help elucidate some of their thinking, let us first consider the relevant information in the story of the Maki brothers.

Step 1: gather relevant information

We are making an assumption that Eino’s situation is caused by his work environment. We can do that for the purpose of encouraging you to think about compensatory justice situations, but of course, in an actual clinical evaluation, your gathering of relevant information first requires clarifying further his stage of lung cancer and whether tests substantiate the source being the asbestos to which he has been exposed as a mining company employee.

Another relevant piece of information that is a question we would have to explore is how much responsibility the company took to help prevent undue exposure. The way risks were presented and action taken to minimize them could make a difference in how we view this situation.

We do know that Eino, and people like him, carry out labor tasks and other societal functions that are needed for the society to function well but often are not valued in other ways and may carry high risks to the workers. Of course, some “high-risk” situations are respected, and individuals who carry out the tasks are given extra financial benefits, and a high status. Examples are firefighters, members of a police force, or U.S. Navy Seals. Others, like Eino, are relegated to greater risk and “less desirable” jobs because of their overall lower social status, often accompanied by poverty or other characteristics that carry a stigma with them. Stigma in this social sense is a term first used by Goffman,2 a sociologist, to depict persons held in low regard because of qualities they have. Status comes into being when mainstream society members, those in control and authority, make arbitrary judgments about the value of different kinds of lives and assign low priority to some whom they devalue. The most explicit negative effect on stigmatized groups comes through their disproportionately small allotment of the society’s goods and services. It can be argued that even if Eino did have the full cognitive capacity to comprehend the danger he was in, he would have been able to do little to change his situation.

Step 2: identify the type of ethical problem

The idea of “compensation” at the root of compensatory justice issues arises out of society’s consciousness that it is the morally right thing to be fair. But not everyone has the same chance at basic lifesaving or life-enhancing benefits from the get-go. Some people are born into situations that, through no fault of their own, force them into a disadvantageous societal position. You are probably familiar with the idea of a “handicap” among competitors in the sports arena. In that environment, good sportsmanship dictates that the handicapped player be given additional “points” to try to make up for the disadvantage. There is an intuitive correctness about this attempt to “even the playing field.” But this compensation activity is not always the case in the larger society, so it is not surprising that the problem it raises is characterized as a dilemma of justice.

Compensatory justice acknowledges due regard for groups of individuals by offering them compensations for harms occasioned by their basic societal disadvantage. The compensation is not necessarily to make up for a consciously perpetrated wrong by another person or society, though one application is criminal justice situations where the perpetrator is required to pay for his or her injury to another. But more generally conceived, it is enough to make it a morally relevant issue that a person or group is vulnerable from the standpoint of having limited access to that society’s available valued goods and services. As for Eino, we have reason to believe that his work in the mines led to a life-threatening, industry-related condition. If the company knowingly placed workers in harm’s way to benefit the company’s bottom line, moral responsibility to redress this wrong squarely can be placed on management. If they, too, are surprised by this bad news, society’s understanding of the wisdom of compensating individuals in such a situation has led to certain mechanisms for spreading the cost of the compensation across the larger society with taxes and other common resources. (In the United States, “workman’s compensation” grew out of this idea originally, but since has come to be considered a protection for anyone injured on a job, no matter their social status, economic security, or other variables.) Sometimes the wisdom of providing compensation has come from pressure by interest groups such as unions or other organizations (e.g., nonprofits run by various religious groups) who try to provide a voice for those who are not in a position to speak effectively against such wrongs themselves. Recently, concern has been expressed in the press and literature that labor unions’ effective voice may be suffering from divided loyalties within the unions themselves.3

However voiced, the idea that a moral claim for compensation should influence how resources are allocated makes this problem a justice dilemma.

Similar reasoning has been applied to priority setting for shelter, food, or other basic goods of society, the underlying assumption being that not everyone comes equally supported by society to adequately take part in life’s basic benefits.

Step 3: use ethics theories or approaches to analyze the problem

In Chapter 15, you were introduced to several ethical theories and principles for analyzing the morally appropriate allocation of resources according to distributive justice reasoning. We present two key ones that clearly also apply to the analysis of compensatory justice reasoning: equity and the principle of nonmaleficence.

Equity

To review, equity means that every effort must be made to treat each person in a similarly situated circumstance alike, allowing for departures from that baseline of equality on the condition that differences are derived from ethically acceptable criteria.

For example, Mr. Maki works in a dangerous environment that is not highly regarded as a career line for mainstream members of society. Other miners are “similarly situated.” They are in a class all their own, equal with each other but not with mainstream society. A compensatory justice approach takes into account that mainstream society has more opportunities and resources to deal with crises such as Eino faces. So “similarly situated” means that all like him fall within the same general category of claimants on health care resources. The compensation in the idea of compensatory justice is that there is a moral pull on a just society to respond to the disadvantages that Eino faces as one who is lower on the rung of the social and economic ladder of society through no fault of his own. It may take priority standing or more societal resources to be sure he receives quality care equal to his mainstream counterparts with similar clinical need. The fact that he is contributing an important service that others usually do not choose adds to the argument that those with more resources have a moral responsibility to help the larger society stay intact through compensations to those like Eino who are less well off.

Where does health care as a right fit into the compensatory justice framework? It certainly helps support the idea of compensatory justice if health care is viewed as a right that everyone should have access to in contrast to the opposite idea that health care is a commodity like all other products to be bought by those who can afford to do so. In some cases, the right may require that those who are better off as members of mainstream society are required to do whatever is needed to support access for all.

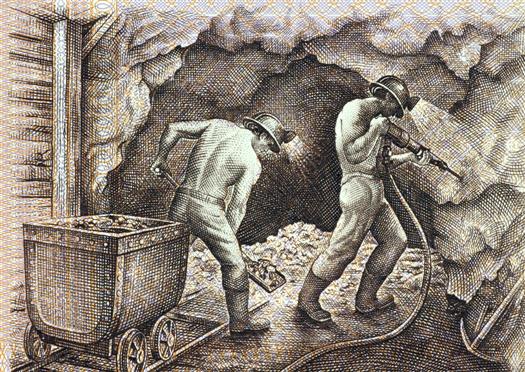

The principle of nonmaleficence

In Mr. Maki’s case, a compelling argument in favor of supporting his medical treatments financially is not only that he has a terrible medical condition (which, indeed, he has) but that he has the condition because he is in a job that carries with it the albatross of a carcinogenic agent that is well established scientifically and can be tested for before damage to a person’s health. Many people examining Eino Maki’s plight have an intuitively sympathetic response in favor of compensating him for his job-related cancer. It seems wrong, from a moral point of view, that he should have to suffer the ravages of a debilitating, painful, and incurable disease because he has been working in a setting that economically disadvantaged individuals are more apt to accept because it is one of the only options open to them and that carries a life-threatening hazard with it (Figure 16-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree