Chapter 14 Compensation and Health Outcomes

Introduction

Insurance provides cover, in the form of financial compensation, against a range of losses, including those arising from personal injury. Insurance is regulated by legislation and the principles of case law, and in many jurisdictions it is mandatory for some parties, such as road users and employers (and others), to purchase insurance.1 Common examples include compulsory third-party (personal injury—auto) insurance, and workers’ compensation insurance, both of which provide compensation to eligible injured parties. While the rationale for specific legislative and regulatory arrangements governing personal injury compensation for injuries varies between jurisdictions, there is common concern for the health and wellbeing of individuals following an injury. Consequently, the question of whether or not compensation and/or the associated processes could affect health outcomes is of interest to academics, clinicians and legislators, and has been examined in some depth primarily in clinical journals (hereinafter, ‘the literature’).

Other things being equal, relieving some or all of the costs of treatment—as most compensation schemes do—should improve the wellbeing of injured people. Compensation schemes usually embody such an insurance function: by alleviating the financial burden of medical expenses that are associated with the treatment of an injury, injured individuals are protected from expenses that, otherwise, would represent ‘random deductions’2 from their incomes/wealth. In circumstances where there is no ‘scheme’ or insurance, but the law establishes a right to compensation for harm, similar principles apply when reparation is made. Similarly, compensation for the lost income, pain, suffering and other adverse effects of an injury should also, other things being equal, leave injured parties better off than they would have been if no compensation were available. However, there are also reasons that the availability of compensation could lead to actual or perceived reductions in health, relative to the situation in which compensation were not provided. Indeed, a negative correlation between compensation and health outcomes has been observed in the empirical literature and has led researchers to pose a hypothesis that may be expressed as follows:

How can this hypothesis above be tested? The counterfactual cannot be observed: the outcome that would have prevailed if individuals had not been compensated cannot actually be known. Similarly, the effect of compensation on those who did not receive it is unknown. Thus, in order to test H0, the influence of compensation on health has to be inferred by comparing the health outcomes of, say, uncompensated and compensated groups. Comparisons of non-randomly allocated groups are problematic for a variety of reasons that have been acknowledged in the literature on compensation and health. To date, though, writers in this literature have, in our view, paid insufficient attention to the implementation of econometric or statistical strategies that may minimise the chance that such comparisons are biased.3

The purpose of the chapter is to explore the reasons that an inverse association between compensation and health outcomes could be observed in practice. It considers the circumstances under which compensation processes and/or outcomes could genuinely lower health outcomes by comparison with the counterfactual. The primary emphasis, though, is on the reasons that the evidence may appear to support the hypothesis that compensation is bad for health, even if compensation and related processes have a zero, or positive, effect on health. The rationale for this focus is that little attention has been paid to these possibilities in the existing literature, which too often proceeds from the observation of a negative empirical correlation between compensation and health outcomes to the causal interpretation that there is a perverse relationship between compensation and health. This is a serious issue, because the results from this literature have already been used to recommend changes to the apparatus of compensation schemes,4 including limits to some types of compensation. The prevailing sentiments are exemplified in the following quote:

‘There is now convincing evidence that when an injured patient receives compensation, their long-term outcomes are worse.’5

Compensation and related concepts

Note that the term ‘compensation scheme’, as defined, is general enough to encompass common law provisions, even where no insurance mandate exists. Finally, note that litigation itself is rare, as most legal actions are settled out of court.1 Indeed, in many jurisdictions, the proportion of matters that proceed to court is extremely small.

Conceptual representation of a compensation scheme and related concepts

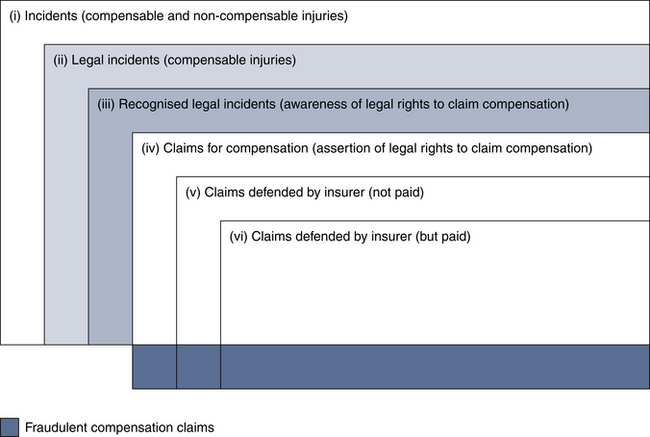

Figure 14.1 is a conceptual representation of compensation processes and outcomes. It is a stylised representation of a compensation scheme and it builds upon the distinctions that Wright and Melville7 have made in relation to litigation per se. The purpose of Figure 14.1 is to provide a way of thinking about the distinction between concepts that are poorly described in the literature. The distinction between these concepts is directly germane to attempts to test the hypothesis that compensation is bad for health.

Figure 14.1 should be read from left to right, and top to bottom. The largest rectangle in Figure 14.1 is labelled ‘(i) Incidents (compensable and non-compensable injuries)’. Rectangle (i) represents all injuries that occur in a particular jurisdiction, irrespective of how or where they occur, who causes them and whether or not they are compensable. The second-largest rectangle, which is marked ‘(ii) Legal incidents (compensable injuries)’, represents the subset of incidents to which legal rights to compensation are attached. The size of this subset, relative to the incident rate of injuries per se, depends upon the laws and institutions that are in place in a given jurisdiction. For example, in Figure 14.1, it is assumed that not all incidents (injuries, in this case) are legal incidents (i.e. compensable injuries). Thus, (ii) provides one way of considering the scope of a compensation scheme.

The rectangle that is marked (iv) represents the proportion of recognised rights that are asserted (i.e. the number of claims for compensation). The part of (iv) that lies outside (i) and is shaded blue indicates claims for injury compensation where no injury exists (i.e. fraudulent claims). Note that individuals could also mistake genuine injuries as compensable (‘Legal incidents’) when they are not and make claims for them; however, for simplicity, these phenomena are not depicted in Figure 14.1. Within the assertions of legal rights (iv), (v) represents the claims for damages that are defended (e.g. by the insurer) and, among these, (vi) represents claims that are defended but nevertheless do result in compensation. Claims that are defended and where no compensation is paid are depicted by the area of (v) that is shaded blue. Finally, note that Figure 14.1 implicitly assumes that some fraudulent cases are successfully defended, but that others are paid.

Definitional considerations (compensation, litigation and lawyer involvement)

One point to be taken from Figure 14.1 is that litigation, compensation, lawyer involvement and other related legal processes and terms are all quite distinct—despite the prevailing tendency to aggregate them, as described in detail by Grant and Studdert.3 Studies in the health literature often use these terms as if they are interchangeable.

Treating ‘compensation/litigation’, for example, as a single, homogeneous category is problematic. Litigation and compensation are not synonymous and, indeed, litigation is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the payment of compensation. Similarly, in the empirical literature the involvement of lawyers sometimes appears to be erroneously equated with litigation or, indeed, compensation itself. Although lawyer involvement obviously is common in litigated cases, in some jurisdictions self-representation may constitute a significant proportion of claims for compensation, especially for smaller claims.

Thus, it is not sensible to treat compensation, litigation, lawyer involvement and other terms associated with personal injury compensation as homogeneous concepts. For example, returning to Figure 14.1, if compensation, litigation and lawyer involvement were treated as synonymous, into which group would the latter two categories fit? Unfortunately, the answer is ‘probably both’, because some individuals who are uncompensated will have pursued a compensation claim, retained a lawyer and engaged in (unsuccessful) litigation of their case. Similarly, a number of compensated individuals may have pursued a successful claim without lawyer involvement. Irrespective of whether a lawyer is involved or not, litigation in this context is uncommon. For example, in Queensland, Australia, only about 3–4% of motor accident compensation cases are litigated,8 with the vast majority of cases being settled out of court.1

Compensation: empirical considerations

Selection bias and confounding have been acknowledged as common problems in research on compensation and whiplash recovery.9, 10 Additionally, as the research is comprised of non-randomised studies, it is not possible to determine whether there is a causal relationship between compensation and health.11, 12

Figure 14.1 shows how compensation payments are preceded by a claims process that is governed by the law, institutional arrangements and, crucially, the choices that parties to a harm make. That process usually commences only if injured parties recognise their legal right to seek compensation and then assert that right by making a claim. Whether and how much compensation is actually paid, if this occurs, then depends upon the legal and institutional framework and processes that are in place and the decisions of the individuals who are subject to them. Not only are compensation payments not randomly nor (usually) automatically allocated, but the entitlement to compensation also varies across jurisdictions and schemes. The non-random nature of the allocation of compensation payments and the systematic differences in the ways that different compensation schemes operate have important ramifications for comparisons between the groups in Figure 14.1, both across and within compensation schemes. The specific issues that are implied for empirical studies that seek to test the hypothesis (H0) that compensation is bad for health primarily involve problems related to selection bias and confounding, which will now be outlined.

Sample selection bias and confounding

It is generally not feasible to randomise the allocation of compensation for experimental purposes. Thus, differences that are observed between compensated and uncompensated individuals, for example, may be due to the treatment, that is, compensation, and due to selection effects. The latter term refers to differences that are not due to the treatment itself, but to factors that vary systematically between those people who seek and those who do not seek compensation. Selection bias may be thought of as an error in the way that individuals are ‘assigned’ to the intervention and control groups.12 Selection bias can lead to confounding as it creates differences between these groups, and the validity of between-group comparisons hinges on whether the groups are composed in a manner that allows for appropriate comparison.13 While it is possible to apply statistical techniques to control for the effects of observed factors, such as age and gender, which may differ between the groups, observational (non-randomised) studies in the clinical literature often do not address the potential for unobserved differences to confound the results.

Sampling problems are not limited to primary studies. Systematic reviews that have investigated the prognostic impact of compensation on whiplash recovery have not searched specifically for compensation-related studies, and thus it is unclear whether the samples of primary studies included in the reviews are truly representative of the existing research.14–16 Moreover, systematic reviews are also subject to the methodological limitations inherent in the primary research on this topic. Attempts to consider the effects of compensation on health are complicated further by authors pooling the results of studies that concern different types of compensation schemes and/or legal processes. The heterogeneity problem is outlined below. Examples of the ways in which the problems of selection bias and confounding may affect the results of studies examining the association between compensation and health status are provided in the following sections.

Cross-jurisdictional scheme comparisons (‘apples and oranges’ problem)

One of the distinctions in Figure 14.1, between areas (i) and (ii), is particularly relevant to attempts to compare individuals’ health outcomes across different compensation schemes. Whether this is the primary purpose of the study (e.g. to compare health outcomes in one jurisdiction versus another), or is simply an incidental aspect of the sample design (e.g. to test H0, the health outcomes of claimants and non-claimants are measured using studies performed in various jurisdictions), there are important empirical implications. Essentially, differences between schemes may create an ‘apples and oranges’ problem that makes inter-jurisdictional comparisons and the policy conclusions that may be based on them problematic.

A review of the law of negligence highlighted the variation in personal injury compensation laws and schemes in Australia.17 This review described how, for example, the amount of compensation for similar injuries differs depending upon which injury compensation law is applicable, as these laws vary according to where and how an injury occurs. Liability rules, the recovery of legal costs, discount rates, award payment structures such as lump sum or periodic payments, and other aspects of scheme design also vary. Such variations are also evident in the laws and processes governing compensation for road traffic injuries, and these differ between and even within some countries, notably, Australia,17 the United States18 and Canada.19 Thus, regional comparisons and broad conclusions about the effects of compensation and the related legal processes on health status are limited in their validity because laws and legal processes differ across jurisdictions.20 In addition, it is unclear which, if any, of the features of compensation scheme design may have an impact on health status as there has been little attempt by researchers to describe these characteristics, let alone attempt to relate their hypothesis to them in a lucid manner. While it is outside the scope of this chapter to present a survey of different compensation schemes, their heterogeneity is demonstrable17 and noteworthy.

This problem can, of course, be mitigated in a number of ways. For example, by restricting the analysis to workers injured in the workplace in both jurisdictions A and B, the extent of bias may be reduced; but what if the compensation schemes in jurisdictions A and B also differ substantially? If, for example, the compensation available to workers in jurisdiction A were less generous, less immediate, of lower quality and provided via a more adversarial claims system, the result could persist even when the sample is limited in this way. Unfortunately, few empirical studies consider such issues, let alone control for them. Typically, compensation is treated as a binary variable where subjects are classified as either ‘compensated’ or ‘not compensated’; details of the size of the ‘dose’ among compensated individuals (i.e. the quantum of compensation) and the ‘route’ by which it is administered (e.g. the legal process and other features of the particular scheme) are infrequently available or described.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree