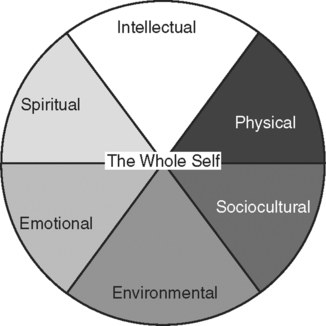

Upon successfully completing this chapter, you will be able to: • State the factors that help determine our health status. • Assist in planning and explaining a diet appropriate for a variety of medical needs. • Explain how to adjust dietary needs for ethnic and age diversity. • Differentiate between food-related medical disorders. • List various exercise options and explain the benefits of each. • Differentiate between positive and negative stress and give the physiologic effects of each. • Describe ways to incorporate relaxation and stress relief techniques into patient education. • Compare methods of coping with stress and determine which are appropriate in various medically related situations. • State ways to recognize suicidal potential and list means of helping patients avoid this option. • Identify substances that commonly lead to abuse and addiction, and describe their effects on the body. • List information to include in educating patients about medication therapy. • Describe ways to ensure the physical safety of various age groups. • Give examples of incorporating alternative and/or complementary medicine into traditional medical therapy. One of our goals as health care professionals is to educate patients in the holistic approach to health. All factors of our “self” must come together for the self-actualization level that includes wellness (refer to Chapter 4, “Educating Patients,” for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs). Holistic medicine works for harmony and balance, or homeostasis, in all areas that make us who we are (Fig. 5-1). This includes our physical being, our mental or emotional self, and our social life and spirituality. Patients are ultimately responsible for maintaining this balance, we cannot do it for them, but we must help them learn to maintain wellness using natural means and prudent choices before they need medical intervention. Many factors work together for holistic health. They include the following: • Genetic endowment: Along with general appearance and other characteristics, we inherit our anatomy and physiology, metabolism, and immune system from our extended family. For example, how well our body resists communicable diseases depends on a strong and intact immune system. Some people never seem to catch a cold or flu, and others seem to attract every passing microorganism. Preventive measures (immunizations, Standard Precautions, and so forth) are a big factor, but so is the strength of our inherited immune system. Likewise, how we metabolize dietary fats, for example, has a strong relationship to whether or not we develop heart disease. How strong and well made our body is (anatomy) and how well it works (physiology) helps determine our general level of health and resistance to disease. • Availability of health care (socioeconomic status): The world’s best medical technology will not help our patients if it is not available to them. Whether a patient can afford prevention measures or to seek help to relieve a medical problem depends largely on financial resources. When the decision is between food or shelter and health care, and the question is “Of all I must pay, which is most important?”, health care, particularly preventive care, may be a low priority. Wealthy patients with better education and better access to health care usually know the symptoms of illness, have regular physical examinations, and schedule diagnostic screenings to manage illness while it is still more likely curable. Financially stable patients usually maintain immunizations for childhood diseases, flu, pneumonia, tetanus, and hepatitis B. Many poorer patients with no access to health care do not have these options. • Family dynamics: A calm, loving home protects us from many stresses and meets our love/belonging and safety/security hierarchical needs. A stormy, upsetting home life gives us no shelter from the stress of the outside world. Family exposure also teaches us how to respond to illness, forms our exercise and diet habits, and shows us how to react to stress. • Culture: The food we eat, our reproductive philosophies, and how we care for our illnesses are all largely cultural and have an enormous impact on health. We have covered cultural factors in the health care setting, and as we work through this text we will see how diet and cultural approaches to health care affect long-term health. • Environmental: Exposure to polluted air, water, soil, or foods stresses even the strongest immune system. Environmental exposure to strong, drug-resistant microorganisms challenges our resistance and may overpower otherwise good health. • Emotional or physical stress: Extremely stressful situations or exposure to moderate stress over a long period measurably decreases the immune response and makes us susceptible to opportunistic disease. This is covered later in this chapter in “The Stress Factor.” • Poor social habits: Smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, a sedentary lifestyle, and overexposure to sun versus good nutrition, exercise, and prudent living all strongly influence long-term health. Imprudent choices lead to STDs, traumatic injuries, early degenerative disease, and generally poor health, regardless of a strong inherited immune system. Help-seeking mechanisms vary also and significantly affect health. Whether we seek help is very cultural and also varies with age, social class, and sex. Patients must recognize that something is wrong, realize that help is needed, and decide on a course of action. Many patients deny they have a problem if they have more pressing hierarchical needs (review Chapter 4, “Educating Patients,” for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs). • Middle-aged and older adults ask for help more frequently than teenagers and young adults. • Educated patients with better financial resources are more likely to recognize when they need care than members of lower socioeconomic groups with less education. • Women ask for help more frequently than men, and mothers of young children are most likely of all to seek help. • The patient’s perception of the illness is also a factor. He may wonder, “Is this a heart attack or indigestion?” Many do not recognize a problem unless the symptoms are identifiable or unusually uncomfortable or painful. Many wait with vague symptoms before asking for help. • If the suspected disorder or symptom is not socially acceptable, patients may decide not to seek help. Patients may wonder, “Do I want anyone to know about this?” Many patients would rather not report symptoms that are potentially embarrassing. For example, consider the following for social acceptance: a vaginal discharge that may be a STD versus a breast lump; skin cancer versus possible Kaposi’s sarcoma; heart disease versus morbid obesity. Pride is associated with some disorders, such as those related to sports; for example, shin splints and tennis elbow. Patients are rarely reluctant to report these disorders. • The age at which the symptoms appear may determine whether the patient or caregiver sees the symptom or sign as significant. For example, for whom would unexplained joint pain be a greater concern, an otherwise healthy 10-year-old or an 85-year-old with multiple health problems? • For working adults, seeking help may depend on balancing available sick leave against the severity of the symptoms. Patients may weigh the options of treating themselves or going for help if they have no more sick days available. • The day of week and the time of day also have an impact on reporting illnesses. Patients are more likely to seek help early in the week or early in the day and are least likely to report illness on Friday or the weekend or late in the evening (Fig. 5-2). Think of what this might mean for someone with unexplained chest pain. When all of the information listed above regarding the patient’s nutritional status is documented and evaluated, education and an appropriate diet can be arranged around the patient’s specific needs. Not everyone responds equally to the same procedures or medication, and the same is true of diets. Two people consuming the same diet respond according to their individual metabolism. One may lose significant weight; the other may simply maintain, neither gaining nor losing. If the health concern involves a nutritional imbalance, such as poor absorption of nutrients or the need for great weight loss, a dietitian or nutritionist should work with the patient. These situations will not respond to the latest best selling one-size-fits-all diet. In cases of morbid obesity, patients may be referred to a bariatrics specialist, a new field that concentrates on obesity and its related disorders. However, in cases that involve nothing more than poor or imprudent food choices, following the current accepted nutritional guidelines almost always leads to better health and more realistic weight regulation. Since the nutritional and dietary sciences constantly update recommendations to reflect new information regarding proper food choices, it is in everyone’s best interest to stay current of the latest dietary theories. Guidelines have been designed to ensure healthy food choices for most age groups, many cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and various diseases and disorders. All can be easily adapted for individual preferences and special needs (Box 5-1). More recently, in recognition of cultural diversity, food pyramids were designed for ethnic groups such as African American, Asian, and Native American. Pyramids also offer healthy food choices for older adults, children, and vegetarians. The World Health Organization (WHO) developed pyramids for other countries that offer the best nutrition based on foods locally preferred and regionally available. Within each group, and within each culture’s traditions, a healthy diet is possible by following the appropriate guidelines (Table 5-1). Table 5-1 CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS DIETARY PRACTICES • Teach patients to eat sensibly using foods from all food groups. Diets that eliminate any food group in the food guide pyramid may not promote long-term health. Following the recommended guidelines should lead to weight loss without compromising health. • Whole grains, raw vegetables, and dark, rough grain breads are good diet choices. These foods are filled with vitamins, minerals, and roughage, rather than empty calories. • Low-fat products are better choices than full-fat products, but help patients learn to read labels. Sugar may have replaced a portion of the fat, making the calorie count even higher than it would have been with the small amount of replaced fat. • Caution patients to limit prepackaged sauce and seasoning mixes, canned soups, packaged deli meats, and frozen meals. The fat and calorie content of these items is usually very high. Teach patients to read labels; the entire RDA of fat and sodium may be found in just one serving of some foods. • When estimating serving sizes not listed on labels as one slice, two chips, and so on, show patients how to use the following guide: 1 ounce is thumb-sized, 3 ounces are about palm-sized, a cupped hand holds about 2 liquid ounces, and a fist is about 1 cup. In order of restriction, modified diets ordered by physicians include the following: • Nothing by mouth (NPO) is not a diet; it is a method of ensuring that the GI tract is empty for procedures such as surgery or GI diagnostic studies. It is also used to rest the tract after a serious illness with vomiting and diarrhea. Unless nutrients are supplied by intravenous methods, patients should not remain NPO for long periods of time. • Clear liquid diets include foods without residue that are liquid at room or body temperature, such as broth, clear juices (no pulp), gelatin, plain coffee or tea, and certain carbonated beverages. This is usually the first diet ordered as patients progress through the postoperative period or after a severe GI upset. Since this diet contains very few nutrients, patients should progress to the next level as soon as possible. • Full liquid diets contain foods based on milk products, soft grains, egg products, fruit juices, and any item included in the clear liquid diet. This is a natural progression from a clear liquid diet when patients are well enough to tolerate heavier food. This diet contains more nutrients than the more restrictive levels but should not be used for long-term management. • Pureed diets may be a regular diet that is processed in a blender or food processor to eliminate fiber to make it easy to swallow without chewing. It is important to make this type of diet as appealing as possible since much of our appetite and pleasure from food comes from eye appeal and texture. This diet can be equally nutritious as a regular diet if the patient must stay on it for long-term management. • Soft diets contain foods from a full liquid diet and from a regular diet. Foods must be easy to chew and digest and must be low in fiber, fat, and seasonings. Soft diets are ordered for patients who can progress from a full liquid or pureed diet but are not ready to chew or swallow a regular diet. • BRAT (bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast) is prescribed for pediatric patients with diarrhea and vomiting. It is nutritious, but the child should progress to a full, age-appropriate diet as soon as possible. • Anorexia nervosa: Patients with this disorder have such a distorted body image that they see themselves as obese no matter how thin they are. Bulimia (described below) may or may not be present. The disorder usually begins in the mid-teens and is found almost exclusively in cultures with plenty of available food but which value thinness as a sign of beauty and high achievement. The majority of the patients are women. Signs of anorexia nervosa include a weight loss of 25% or more for no apparent reason, with a perceived need to lose even more weight. Starvation may progress to death in up to 15% of the patients. Treatment may require psychiatric hospitalization if the patient’s condition cannot be controlled in the outpatient setting. (Note: The term anorexia means “lack of appetite.” Anorexia is usually the result of illness. Anorexia nervosa refers to a psychological abnormality in body image perception.) • Bulimia nervosa (also known as binge and purge): Patients usually are aware that this is not normal behavior but are powerless to change it. Bulimics are usually women and girls from families that expect a high degree of success. Unlike the anorexia nervosa patient, bulimics may maintain a normal weight even though they consume large amounts of food. After eating, they usually induce vomiting and/or purge with laxatives. Obsession with weight and body image are clues, as are foul breath and tooth decay from regurgitated stomach acids. Treatment focuses on breaking the cycle and helping patients come to terms with the stress caused by the need for perfection. • Compulsive overeating: Patients with the direct opposite of the above eating disorders are those whose eating habits result in obesity with weight 20% or more above the ideal for their frame. Obesity increases the risk of both forms of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and complications from surgery or pregnancy. Depression is high among overweight patients because of our society’s emphasis on thinness. Some patients have organic reasons for their overweight, such as genetic predisposition and certain endocrine disorders. However, many others use food as an escape from stress or simply do not understand the need to balance the intake of calories with an output of energy. Treatment requires life-long behavior modification, usually under the care of a professional therapist if the overeating has a psychological basis. Patients with no contributing health problems who blame any factor other than their own behavior rarely change their destructive eating habits. Unfortunately, fewer than 30% of patients with personality-related obesity achieve and maintain an appropriate weight for very long. • Semi-vegetarians may eat poultry, fish, and dairy products but usually will not eat pork, beef, or other red meat. • Macrobiotic vegetarians eat whole grains, vegetables, and seafood (usually fish products) but will not eat processed food. • Lacto-ovo vegetarians eat vegetables, dairy products, and eggs. • Lacto-vegetarians may use milk-based products but will not eat eggs. If your patient decides to limit or eliminate meat, suggest these guidelines: • Rather than expecting the body to adjust to an immediate withdrawal of its usual protein source, the patient should phase meat out gradually. Initially, meat should be limited to one meal with meat per day, then one meat meal every 2 days, and so forth, until the body adjusts. • Meat can be replaced or eliminated in many recipes; for example, vegetarian chili, marinara spaghetti sauce, stewed vegetables without meat. • Grains, peas and beans, and other sources of fiber should be increased gradually. All are good sources of essential vitamins and minerals. However, if the quantity is increased too quickly, the increase in fiber may cause gastrointestinal distress. • In the absence of meat, the diet should include a variety of foods. French fries and macaroni and cheese are vegetarian, but a steady diet of heavy fats is less healthy than one that includes red meat. • Vegetarians should choose fortified products. Many vegetarian diets are low in certain vital nutrients, such as vitamin B12. • Consider age and sex when structuring a diet. Women and children must supplement calcium intake to ensure bone health. Women of child-bearing age must increase iron intake. Older adults usually have at least one of the following problems that interfere with good nutrition: • Slowing gastrointestinal function that delays elimination and increases indigestion • Poor dental care or poorly fitting dentures that make chewing difficult or painful • Decrease in the sense of smell and taste leading to poor appetite • An increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease that brings food and acids from the stomach back to the esophagus, leading to pain and erosion (eating away) of the lining of the esophagus • Depression and loneliness, making mealtime less enjoyable • Low income, making good food choices difficult • Multidrug interaction with foods, increasing indigestion and decreasing appetite • Encourage patients to maintain good dental health. Food is easier to eat and feels better in the mouth with real teeth rather than dentures. Overall health will improve with better dental health and hygiene. • Teach patients how to keep a food diary for at least a week; a month is even better. Tell them to be honest about the serving sizes. Help them calculate their calories and fat grams against the recommended intake. • Encourage patients to slow down and concentrate on the meal, rather than reading or watching TV while eating. Meals should not be eaten on the run or while doing other things. • Teach patients to fill a small plate with small to moderate amounts of good-quality, healthy food; empty space on a large plate looks as if it should be filled. Urge dieters not to go back for seconds. • Caution dieters not to eat out of boredom, depression, or anger. Encourage them to take a walk or ride a bike instead. • Tell patients they should expect to lose weight slowly. Losing weight too quickly is not safe for good health and usually leads to regaining it just as quickly. • Dieters should resist buying junk food; if it is not close at hand, impulse snacking is less likely. • Caution dieters that caffeine intake should be kept to less than 200 to 300 mg per day. One cup of coffee has about 100 mg of caffeine and most soft drinks have comparable amounts. • Encourage dieters to bake, broil, grill, or saute lean meats, poultry, and fish rather than frying. • Using herbs and spices rather than salt, fat, or sauces highlights the taste of food without adding calories or fat. • Six to eight glasses of water a day keeps tissues hydrated and helps elimination. A large glass of water before a meal may help the dieter eat less. • Skipping meals is not a good idea. The dieter usually will eat more at the next meal or fill up on junk food.

COMMUNICATING WELLNESS: WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BE HEALTHY?

WHAT MAKES US SICK

THE NUTRITION GOAL: WE ARE WHAT WE EAT

Food Guide Pyramids

Group

Prohibitions

Preferences/Requirements

Catholics

Fast or abstain on certain holy days

Hindus

Range widely from prohibiting all meats and animal products to more lenient practices

Yogurt, beans/peas, prefer to balance hot with cold and sweet with sour

Islamic/Muslims

Pork, alcohol and its products (includes alcohol-based medications), shortening made from animal products, gelatin made from animal products

Jews

Pork, shellfish, and scavenger seafood (shrimp, crab, catfish), milk and meat dishes together, blood or bloody products, such as rare meat or blood sausage

Fish with fins and scales, Kosher products

Mainline Protestants

May forbid alcohol or tobacco, may fast for certain occasions

Mormons

Alcohol, tobacco, and stimulant beverages (colas, coffee, tea)

Seventh Day Adventists

Pork, shellfish, and certain other seafood, fermented beverages

Just What the Doctor Ordered

Eating Disorders

Adjusting for a Vegetarian Lifestyle

Healthy Nutrition for Everyone

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

COMMUNICATING WELLNESS: WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BE HEALTHY?

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue