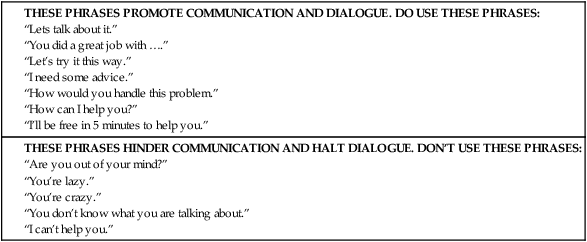

Upon successfully completing this chapter, you will be able to: • Explain the concept of professional etiquette. • Define the term interdisciplinary communication. • Explain your role in participating in a case conference. • Define the terms emergent, urgent, and nonurgent and provide an example of each. • Describe common communication challenges and the strategies to overcome them when communicating with coworkers, physicians, managers, and regulatory agency personnel. • Describe the guidelines for communicating with referral personnel. • Respect each person’s knowledge and skill level. • Accept each person’s contribution to the health care team. No one person or specialty is more important than another. • Workplace communication should be free from inappropriate topics, jokes, or betting. Ethnic/cultural jokes can easily be misinterpreted and therefore must always stay out of the work environment. Maintain patient and staff confidentiality. It is inappropriate to gossip or spread private information with other team members or patients. For example, it is unprofessional to say, “Did you hear that Dr. Raymond is getting a divorce?” or “I heard that he is involved in a big malpractice case.” • Always adhere to your professional organization’s code of ethics. Communicating with various health care workers is termed interdisciplinary communication. Interdisciplinary is the combination of two or more specialties working together to meet a specific goal. The main goal of interdisciplinary communication is to promote optimal patient care. Each specialty (Box 8-1) provides a unique viewpoint and treatment plan for the patient and family. Interdisciplinary communication also • Promotes teamwork, thus improving staff productivity and efficiency. • Improves the patient care environment. • Meets the requirements of various regulatory agencies. • Helps to create or revise policies and procedures that affect more than one department. There are five specific groups of professionals with whom you must be able to communicate: • Age: Your coworkers may be younger or older than you. Differences in age may affect your ability to communicate openly and easily. Here are three examples showing how age can affect communication. • Newer medical terms replace older terms. For example, the term nodal (type of ECG rhythm) has been replaced by the term junctional; rales (type of breath sounds) are now commonly referred to as crackles. • Newer methods of performing standard skills can create challenges unless the health care provider attends continuing education courses. For example, “In CPR, we always gave five compressions to one breath for two-rescuer adult CPR. Who taught you 15 compressions to two breaths?” In this example, the provider took CPR in school years ago, but the ratios have changed. • Age differences can limit our ability to feel like a member of the team. For example, if everyone you work with is younger or older than you, and they often socialize after work, your age difference may prevent participation. This may keep you from feeling like you are part of the team. • Different goals and objectives: Everyone has different goals or objectives for working. Some of your peers may have hopes to become the next manager, whereas others may plan to retire in 6 months. Here is an example of how this can affect communication: • Jackie, who hopes to become the next assistant manager, is always thinking about ways to promote herself. She may start a conversation saying, “I think we need to redesign our documentation flow sheet.” • Tonya has four children, works part time, and has no desire to expand her role. She quickly responds, “What is wrong with the one we have now?” • Jackie: “It’s old and outdated” • Tonya: “Stop inventing projects. You are so difficult to work with.” • While Jackie may have a valid point about the documentation sheet, these four sentences have left two coworkers at odds with each other. • Different work ethics: Some people do 110%, while others opt to squeeze by at 75%. A statement such as, “When you see the gauze sponges are getting low, you should restock the wound dressing cart,” can lead to a poor working relationship. Again, this may be a valid point, but it comes across as a negative statement and does not engage communication to resolve the problem. • Best friends: A coworker can be your best friend outside of work, but in the work environment, you may come to resent covering your friend’s inadequacies. Here is an example: • Sue: “I won’t be able to get out on time and go shopping with you.” • Sue: “Because I haven’t even started charting yet and I have two medications to give.” • Barbara: “How did you get so far behind?” • Sue: “I was trying to get a date with that new resident.” • At this point, Barbara must decide whether to help her friend or go shopping alone. Helping out a best friend on a regular basis can strain any relationship and lead to the inability to work together effectively. This problem can be resolved easily with open communication about feelings and expectations. Present the problem (explain the problem as you see it): “Today, I was trying to teach a patient how to use a home glucometer. We could hear your laughter in the hall.” Explain (explain how the problem makes you feel): “I felt really embarrassed when I was talking to the patient.” Effect (explain the effect the problem has on your ability to do your work): “It bothers me because I have to repeat my message and I feel that I have to apologize for the loud noise.” Resolve (explain that you want to resolve this problem so that you can work together better): “I really enjoy working with you and I want us to be able to work as a team, so I would like to resolve this problem. Can you try to lower your voice when sitting at the desk?” • Remember: there is a time and place for everything. Avoid any type of communication that may alienate a coworker or patient (Fig. 8-1). • Humor can provide stress relief, but be cautious using it in the workplace. Appropriate humor may consist of a funny story or tale but must never include sexual or ethnic content. Practical jokes or setting bets is not appropriate in the workplace. • Accept everyone. Value individual skills and strengths and accept weaknesses, and in turn, others will accept your strengths and weaknesses. • Stay within your boundaries. It is not your job to discipline or reprimand another employee. The supervisor must handle these tasks. • Never criticize or question a peer’s performance or professionalism in front of other colleagues or patients. Instead say, “Before we leave today, I would like to talk with you about something. Can we meet in the lounge at 3 pm?” and bring the discussion into a private area. Table 8-1 offers suggestions for phrases to use—and to avoid—when speaking with coworkers. Contact the physician STAT for situations such as the following: • Life-threatening change in a patient’s condition • Sudden deterioration in a patient’s condition • Laboratory or radiology results that require immediate interventions Contact the physician (non-STAT) for situations such as the following: • Clarification or changes to medications that are not life-threatening. For example, a patient may call the physician’s office and tell you that his morning blood sugar was 210. The patient wants to know if he should increase his evening insulin dosage. This situation is not an emergency, but it must be handled in a timely fashion. If the patient had called the office reporting a very high or low blood sugar or was experiencing symptoms, then the physician would need to be contacted STAT. • Patient care concerns that require urgent care. For example, a nurse from a skilled nursing facility has called a physicians office and told you that a patient has developed a new skin ulcer. This patient deterioration does not warrant an emergent page but needs to handled in a timely manner (Box 8-2). Leave a message (e-mail, voice mail, or secretary) in situations such as the following: • Normal laboratory or radiology results • Positive patient care updates • Patient or family/caregiver requests to speak with the physician about a nonurgent matter • Intimidation—As a newcomer to the medical field, you may feel intimidated speaking with a physician. This is understandable and very common among new graduates. These feelings will subside as your experience level increases, your comfort level grows, and you become more acquainted with the physician. • Different personalities—Each physician is an individual with a unique personality. Some physicians are very outgoing and happy to answer your questions, whereas other physicians may appear to be short tempered. Do not allow personality issues and reputation to interfere with the need to contact a physician. If you find yourself avoiding a physician, speak to your manager and create a resolution plan. You must work to overcome any communication obstacle.

COMMUNICATING IN THE WORKPLACE: IT’S MORE THAN JUST PATIENTS

WORKPLACE COMMUNICATION: THE BASICS

Professional Etiquette

Interdisciplinary Communication

COMMUNICATING WITH MEMBERS OF THE HEALTH CARE TEAM

Coworker/Peer

Communication Challenges

Practical Tips

Physicians

Guidelines for Contacting a Physician

Communication Challenges

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

COMMUNICATING IN THE WORKPLACE: IT’S MORE THAN JUST PATIENTS

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue