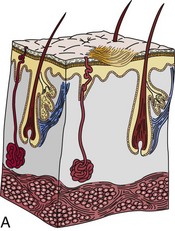

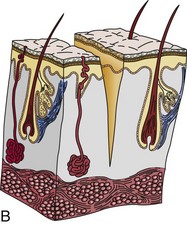

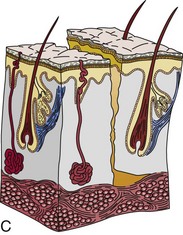

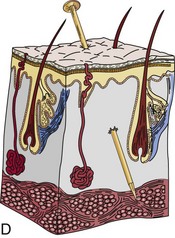

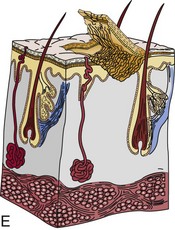

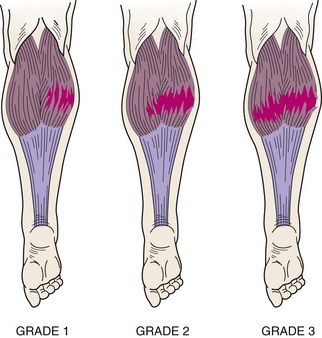

Chapter 17 After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following: 1 Describe and apply appropriate massage for the following common syndromes and injury categories: b Muscle soreness and stiffness c Muscle cramp, spasm, and guarding This chapter categorizes similar injuries into general treatment protocols for massage application. What changes are the targeted locations. For example, a sprained knee or wrist is similar in basic pathology, and only the anatomy is different. A wound on the leg or the foot is still a wound. Specific treatment strategies are provided for these general categories, which then are applied to specific injuries by region in Chapter 20. The student will need an orthopedic injury text for further information. Common warning signs of overtraining include the following: • Mild leg soreness, general aching • Washed-out feeling, tired, drained, lack of energy • Sudden drop in ability to run typical distance or times • Insatiable thirst, dehydration • Lowered resistance to common illnesses such as colds and sore throat 1. Describe the application of appropriate massage for the following common syndromes and injury categories: Muscle soreness can be produced by many types of muscular activities. A common deterrent for ongoing interference with physical activity is post-exercise soreness from movements that produce tension as the involved muscles are forced to lengthen. The muscle actions needed for these movements are known as eccentric or negative actions. These types of movement activities include movements that resist gravity or forward momentum, such as downhill running, lowering of heavy barbells, and the downward phase of push-ups or sit-ups; movements that resist forces exerted by stronger opponents, such as performing a pin or a hold in wrestling and a block in football, are also eccentric. Current explanations for muscle soreness include lactic acid accumulation, muscle spasms, and muscle damage. Lactic acid and muscle spasms have been largely discredited as reasons, but as described in Chapter 3, the muscle damage explanation has a sound scientific basis. • Warm up thoroughly before activity and cool down completely afterward • Use easy stretching after exercise • Start an exercise program with easy to moderate activity and build up intensity over time • Avoid making sudden major changes in the type of exercise • Avoid making sudden major changes in the amount of time spent exercising Make sure the client has no skin sensitivity to an ointment that will cause an allergic reaction. The three types of contusions are intramuscular, intermuscular, and bone bruise. Symptoms of contusions include the following: If after 2 to 3 days the swelling has not gone, an intramuscular injury is likely. If bleeding has spread and has caused bruising away from the site of injury, the injury is likely to be intermuscular. Contusions are classified as grade 1, 2, or 3, depending on severity (Box 17-1). Wounds can be classified as follows (Figure 17-1): • Abrasion. In this wound, the outer surface of skin has been scraped away. Usually some minor oozing of blood and serum occurs. • Incision. A wound of this kind is made with a sharp, knife-like object that leaves a cut with smooth edges. Incisions are often part of surgical care procedures. • Laceration. This wound type is similar to an incision but with jagged edges caused by a tear. Because incisions and lacerations go beyond the outer layer of skin and into the deeper layers that contain blood vessels, a lot of bleeding occurs. If the wound is deep enough to cut an artery, blood will squirt out with each heartbeat because of high pressure in these vessels. Care involves applying pressure dressing and getting the victim to medical care, during which sutures usually are needed to close the wound fully or partially. • Puncture. As its name implies, a puncture occurs when a foreign object is pushed into the skin. The wound can be superficial or deep. Minimal bleeding is evident externally, but internal bleeding can occur. A deep puncture wound requires medical care, and a tetanus injection may be required. Some arthroscopic surgical procedures produce wounds that are more like punctures than incisions. • Avulsion. With this type of injury, the skin is pulled or torn off. Severed tissue should be saved and taken to the hospital. A pressure dressing is applied over the wound until medical care is received. Once a dressing is applied, leave it alone and do not take it off to check the wound. Follow these guidelines when performing therapeutic massage for wounds (Figure 17-2). FIGURE 17-2 Therapeutic massage application for wounds and contusions. Wound, subacute early (3 to 5 days). Sanitation and infection prevention are essential. Proceed with caution. Avoid the area during massage to protect the wound from contamination. Old scars that are adhered to underlying tissue can be softened and stretched. All mechanical forces are used in multiple directions on the scar at each session until the scar tissue and tissues at least 1 inch away from the scar become warm and slightly red. The intensity should be enough that the client experiences a burning stretching sensation (Figure 17-3). A small degree of inflammation is desired, and the area may be a bit tender to the touch after the massage but not painful to movement. Ideally, treatment should occur every other day, allowing the tissue to recover on alternate days. These methods can be taught to the client or family member. Note: A specific massage treatment protocol for strain and sprains is provided on p. 299. A strain is a stretch, tear, or rip in the muscle or in adjacent tissue such as fascia or muscle tendons (Figure 17-4). Strains also are called pulls and tears. The cause of muscle strain is often not clear. Often a strain is produced by an abnormal muscular contraction during reciprocal coordination of agonist and antagonist muscles. This type of injury often occurs when muscles suddenly and powerfully contract. Possible explanations for the muscle imbalance may be related to a mineral imbalance caused by profuse sweating, fatigue, metabolites collected in the muscle itself, or a strength imbalance between agonist and antagonist muscles. A muscle may become strained or pulled—or may even tear—when it stretches unusually far or abruptly. A muscle strain may occur while slipping on the ice, running, jumping, throwing, lifting a heavy object, or lifting in an awkward position.

Common Categories of Injury

Overtraining Syndrome

Muscle Soreness and Stiffness

Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness

Contusions

Wounds

Therapeutic Massage Application for Wounds

Massage Applied Days 1 to 3

Old Scars

Strains

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree