As Sam’s case manager or rehabilitation worker, how can you help him?

Step 1: start with some psychoeducation

Episodes of mental illness can lead to significant changes in social and occupational roles. These very real losses can erode self-esteem and diminish expectations of a positive future. In addition, stigma and shame may further demoralise the person and undermine active efforts to change. Psychoeducation that normalises the person’s lived experience but also instils hope is a critical first step in promoting engagement in active rehabilitation.

There are four important messages for Sam.

- Problems with concentration and memory are very common among people affected by mental illness – you are not on your own with this and these problems do not mean that a person is weak or lazy.

- Pessimistic thoughts and feeling demoralised about the prospect of recovery can undermine attempts to change and this might lead to giving up. Getting structured help and support from another person is sometimes a necessary first step to help take back control of one’s life.

- The problems may not be anything to do with the medication – you started the medication around the time it became clear you were developing a mental illness so the problems are just as likely to be caused by the illness itself as the medication.

- Regardless of whether the problems are caused by the illness, the medications or both, you can work on your memory and concentration, develop your capacity with both and greatly improve your chances of success with work and study.

Step 2: get an accurate baseline assessment

You and Sam both need to know the nature and extent of his concentration and memory problems. It is also sensible to identify his other cognitive strengths and weaknesses as well as his level of insight into his cognitive difficulties. Determining the level of insight becomes very important when the person underestimates or overestimates their level of impairment. Underestimation may feed demoralisation because of a tendency to set unreasonably ambitious goals and overestimation of deficits can decrease motivation and promote apathy. Many useful assessment tools are now available in the public domain and can be used by any appropriately qualified mental health worker. The use of others may be restricted to specially qualified practitioners.

Neuropsychological assessment

One way of determining Sam’s relative cognitive strengths and weaknesses is to get a full neuropsychological assessment. This is a very thorough assessment, using sophisticated standardised measures, that provides a detailed profile of cognitive functioning. It is the best means of evaluating cognitive deficits but it is not always feasible as it depends on the availability of appropriate specialists and may be costly.

If you do not have access to someone who can conduct a neuropsychological assessment, we recommend the use of some of the measures discussed in Chapter 2 of this book (e.g. the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BACS). There are two excellent resources by Lezak et al. (2004) and Strauss et al. (2006) that contain comprehensive descriptions of a large variety of cognitive tests, organised according to the cognitive domain under evaluation. Some widely used tests such as the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test and the Trail Making Test are in the public domain and the materials, instructions and norms can be obtained directly from the books. Others such as the Symbol Digit Modalities Test are quite inexpensive. These tests do not require extensive training for effective use but we recommend completing a number of practice trials with friends and colleagues to ensure scores are not affected by clumsiness in administration of the test. When possible, use tests that have parallel or multiple equivalent forms. This reduces the chance that any improvements seen with repeat assessments over time are attributable to practice effects.

A complementary approach that is a less resource-intensive alternative to formal neuropsychological testing is to use an interview-based measure of cognitive functioning. Measures such as the Clinical Global Impression of Cognition in Schizophrenia (CGI-CogS; Ventura et al., 2008) and the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS, available from the author on request – richard.keefe@duke.edu) (Keefe et al., 2006) have been developed specifically to assess the types of subjective cognitive complaints that affect daily functioning in people with schizophrenia. An important feature of these measures is that they require the practitioner to obtain input from someone who knows the person with schizophrenia well enough to comment on their levels of cognitive difficulty. This can reveal discrepancies between the person’s subjective abilities and their actual level of functioning. Even if a formal interview measure is not used, it is good practice to gain collateral information from a third party. This should be done at the initial assessment and repeated at regular intervals during the remediation programme.

If it is difficult to access either a neuropsychologist or a standardised test you can administer yourself, we recommend you encourage Sam to use a website such as http://cognitivefun.net/. This site contains a neat set of online tests and allows the user to maintain a record of performance. (Most of these sites require the user to create an account and log on each time in order for progress data to accumulate. If you are going to use this method of monitoring improvements over time, it is important that you ensure that the patient understands that they need to log in each time they complete a training session.) There are also some similar tests on http://cognitivelabs.com, although this is a more commercial site and does not allow the same easy monitoring of performance. Other websites that offer online recording of performance are provided at the end of this chapter.

Assessment of awareness of cognitive deficits

It is well known that people with schizophrenia can display different levels of insight into their symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. However, they can also show varying awareness of their cognitive abilities (Medalia & Lim, 2004) and difficulties with day-to-day functioning (Bowie et al., 2007). Substantial discrepancies between subjective ratings of difficulties, those provided by mental health workers and the results of structured tests are common. These discrepancies may impinge on the person’s motivation to engage in a remediation programme and so it is advisable to assess their level of awareness before commencing treatment.

A number of scales have been developed to assess the subjective awareness of cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia. For example, the Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia (SSTICS; Stip et al., 2003) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that addresses impairments of memory, attention, executive function, language and motor abilities. The items address cognitive problems that will impair everyday functioning (e.g. ‘Do you forget to take your medication?’ and ‘Do you have difficulty memorising things such as a grocery list or a list of names?’) rated on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘never’ to ‘very often’), with higher scores indicating more frequent problems. This type of measure will be particularly useful with people like Sam who can recognise that they have some cognitive problems.

However, when there is less agreement about the presence, nature and extent of any cognitive difficulties, it will be appropriate to use a measure that incorporates the practitioner’s judgement about the person’s level of awareness of their difficulties. The Measure of Insight into Cognition – Clinician Rated (MIC-CR; the MIC-CR record form and manual are available on request from Dr Alice Medalia – am2938@columbia.edu) (Medalia & Thysen, 2008) is a 12-item semi-structured interview specifically designed to index insight into cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia. The structure and response format are similar to those used in the Scale for the Assessment of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD; Amador et al., 1993) and the items assess both the recognition of a problem (e.g. awareness of trouble listening or paying attention) and the beliefs about the cause of the problem (e.g. it is due to mental illness, it is possibly related to mental illness, or it is unrelated to mental illness). In Sam’s case, his assertion that the problems with concentration and memory started when he was first prescribed medication indicates some ambivalence about attributing his cognitive symptoms to the effects of schizophrenia.

Assessment of the functional impact of cognitive deficits

One of the main challenges with cognitive remediation programmes is getting the effects to generalise beyond the exercises and drills to ‘real-world’ outcomes such as the capacity for effective work or studying (Wykes & Huddy, 2009). There is some evidence that generalised benefits will be enhanced when cognitive remediation is provided in conjunction with interventions that target the achievement of meaningful life goals such as vocational rehabilitation (Bell et al., 2008). Hence, an important part of the assessment process will be identifying behavioural outcomes that will be meaningful in the everyday life of the person with schizophrenia. This may be done informally by discussing the goals that the person wants to achieve when they have completed the remediation program or via the use of structured assessments that identify areas of functional strength and weakness.

One simple strategy for determining the general impact of cognitive deficits on daily functioning is to scrutinise the responses to items on the CGI-CogS and SCoRS described above. Other options that are freely available in the published literature include the five-item Patient Perception of Functioning Scale (Ehmann et al., 2007) and the 14-item Life Functioning Questionnaire (Altshuler et al., 2002). However, a number of scales have now been subject to expert review to determine their suitability for measuring ‘real-world’ functioning in people with schizophrenia (Leifker et al., 2011). Leifker et al.’s study refined an initial pool of 59 measures down to four scales that are currently the most strongly endorsed by expert clinical practitioners and researchers. Two are hybrid measures that assess both everyday living skills and social functioning: the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (Heinrichs et al., 1984) and the Specific Levels of Functioning Scale (SLOF; Schneider & Struening, 1983). The other two measures that received strong expert endorsement are primarily measures of social functioning: the Social Functioning Scale (Birchwood et al., 1990) and the Social Behaviour Schedule (Wykes & Sturt, 1986). All of these measures can be administered by trained mental health professionals and provide comprehensive everyday functioning data that complement information about cognitive deficits obtained from formal neuropsychological testing.

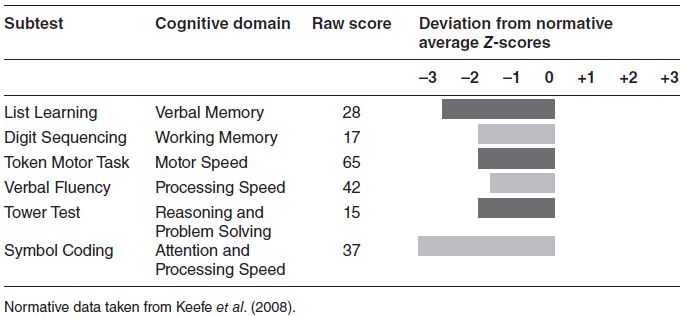

Table 9.1 Sam’s raw scores and standardised Z-scores on BACS subtests.