Coarctation of the Aorta

Mary J. H. Morriss

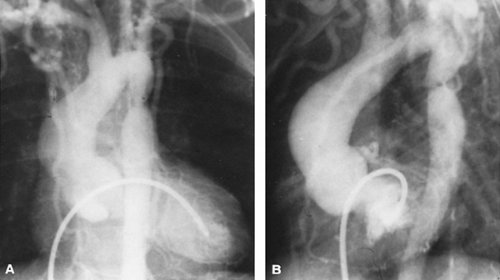

Coarctation of the aorta is a congenital malformation characterized by a constriction of a segment of the aorta. Usually, an abrupt narrowing of the lumen of the vessel occurs in the thoracic descending aorta, producing obstruction to blood flow (Fig. 276.1) A localized shelflike thickening of the media protrudes into the lumen just beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery, leaving an eccentric orifice displaced toward the usual site of insertion of the vestigial ligamentum arteriosus. To be clinically significant, the narrowing must be marked and must reduce effectively the diameter of the aorta by at least 50%. To maintain flow and adequate perfusion pressure to the kidneys and lower body, blood pressure proximal to the obstruction becomes elevated.

OCCURRENCE

Coarctation of the aorta is a common congenital defect occurring in frequency just after ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus in most series. It has a striking male-to-female preponderance in excess of 2:1. Patients with the full XO Turner syndrome with ovarian agenesis and short stature have a high incidence of coarctation in 20% of cases. A more extreme anomaly with complete interruption of the aortic arch in a slightly different location, proximal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, has a high association with DiGeorge syndrome, with deletion in the critical region of chromosome 22q11, and is functionally analogous to severe coarctation with a reverse ductus arteriosus.

CLASSIFICATION

A clear anatomic distinction can be made between an isolated, discrete coarctation (referred to by some investigators as adult or postductal coarctation) and a more diffuse, long-segment narrowing. The latter usually is part of a coarctation syndrome with other more complicated heart defects, resulting in a systemic right ventricle and right-to-left shunting through a persistently patent ductus arteriosus (preductal or infantile coarctation). Rarely, multiple sites of coarctation or an atypical location, such as abdominal coarctation, thought by many to be an acquired disease in association with nonspecific arteritis, may occur.

EMBRYOLOGY

The Skodaic theory of causation is based on an observation that smooth muscle from the ductus arteriosus extends into the aorta, and, when ductal constriction occurs after birth, traction on the aorta can narrow the lumen and cause coarctation of the aorta. The general agreement is that ductal closure can unmask a coarctation lesion, but the theory does not explain the location of the shelflike protrusion of the aorta arising from the wall opposite the ductal insertion. Conceptually, an explanation easier to accept is that alterations in intrauterine flow patterns promote diffuse narrowing in the isthmic region between the origin of the left subclavian artery and the ductus arteriosus, which postnatally is recognized as coarctation. Coexistence of a large ventricular septal defect, or even bicuspid aortic valve with mild obstruction, may divert flow from the aorta into the pulmonary artery, with resultant reduction in the amount of flow crossing the isthmus, the point at which natural separation occurs between flow to the upper body and flow to the lower body in utero.

PHYSIOLOGY

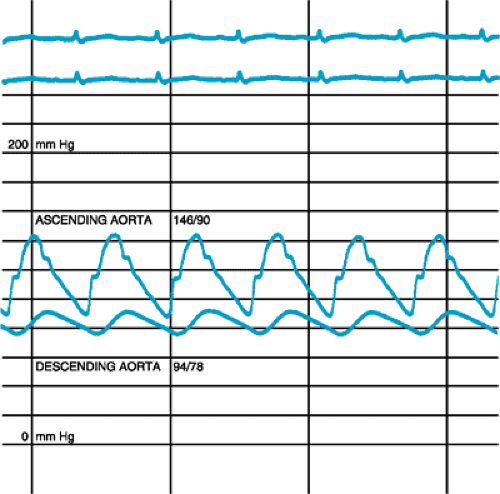

The major physiologic burden imposed by coarctation of the aorta is an increase in afterload of the left ventricle. By the time the aortic lumen is moderately constricted, an increase in systolic pressure occurs above the obstruction, and a lesser degree of elevation is noted in diastolic pressure, with widening of the pulse pressure. Below the coarctation is a narrowed pulse pressure, with decreased systolic and diastolic pressure (Fig. 276.2). These alterations in wave form are reflected by a tactile sensation of delay between radial and femoral pulses. Hypertension is not related directly to the severity of obstruction and may not be extreme. Left ventricular hypertrophy develops, and stimulation for development of collateral vessels to bypass the obstruction occurs.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Coarctation Beyond Infancy

Coarctation of the aorta beyond infancy is recognized clinically when blood pressure recordings are obtained from all four extremities; its hallmark is hypertension in the upper extremities and decreased blood pressure in the lower extremities. The discrepancy in blood pressure, rather than an absolute level of proximal blood pressure elevation, is the most striking finding; however, evaluation of any patient with hypertension should exclude coarctation as a cause. Most individuals with isolated coarctation have no cardiac symptoms, although minor complaints of cold feet, leg cramps, and nose bleeds often are volunteered. Unilateral headaches, particularly of unusual severity, rarely point to an associated cerebral aneurysm, but they may be worrisome enough to prompt performing a full neurologic evaluation. Physical examination shows striking inequality between the strength of pulses from vessels arising proximal to the obstruction and those distal to the obstruction. Simultaneous palpation of brachial and femoral pulses is recommended; in the presence of well-developed collateral vessels, femoral pulses can be felt easily despite the presence of a coarctation, and the discrepancy in timing and pulse volume should be sought. Auscultation should be performed systematically in an attempt to explain the auscultatory findings, rather than with a prejudice that a particular murmur always is found with coarctation. A systolic murmur generated from the coarctation site may be heard best in the left infraclavicular area, in the axilla, or over the left posterior chest. The murmur may seem to originate after the first heart sound, accentuate in later systole, and extend into diastole. The murmur reflects an apparent lag between cardiac systole and flow through the coarctation site, as well as the persistence of a coarctation gradient in early diastole.

True continuous murmurs may be generated by collateral vessels. The presence of an aortic ejection click and an ejection murmur in the aortic area may raise suspicion of an additional bicuspid aortic valve, which is found with high frequency in as many as 85% of patients with aortic coarctation. A thrill at the right upper sternal border or suprasternal notch may accompany significant aortic stenosis, but it also can be found with coarctation alone because of rapid ejection into the dilated proximal aorta.

Despite the presence of a significant aortic coarctation, the results of the electrocardiogram may be normal in older children. When changes occur, they are manifested chiefly by voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy. The rare patient with severe coarctation and left ventricular dysfunction additionally may have ST-T wave changes indicative of ischemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree