Chapter 2 Clinical presentation of whiplash associated disorders

Symptoms following whiplash injury can be diverse in nature. The predominant symptom is neck pain and it is present in almost all patients,1 with some patients also reporting neck stiffness.2 In addition, headache has been reported in 50–90% of patients, shoulder and arm pain in 40–70% of patients and back pain (thoracic and/or lumbar regions) in 35% of injured people.1, 3, 4 Paraesthesia and/or anaesthesia, usually in the upper limbs, presents in up to 20% of patients.2 Apart from pain, other common symptoms include dizziness, visual and auditory disturbances, temporomandibular joint pain, photophobia and fatigue.1, 2, 5 Symptoms of dizziness have been shown to be related to postural control disturbances, including proprioceptive deficits, disturbed eye movement control and balance loss,5–7 and these are discussed in depth in Chapter 7. Cognitive difficulties, such as the loss of concentration and memory, are also common, although the cause of these difficulties remains elusive and there is no evidence to date that they are related to a diffuse brain injury.8 Possible other causes include pain intensity, psychological factors, such as anxiety, or medication usage.8

Patterns of recovery

The onset of symptoms may occur immediately or, in many patients, may be delayed for up to 12–15 hours.2, 9 Recent systematic review data indicate that up to 50% of injured people will not have fully recovered one year post injury.10 Prospective studies that have followed whiplash-injured people from soon after injury to either recovery or the development of chronic symptoms indicate that rapid improvement occurs in the first three months with little, if any, change after this period.11 However, these conclusions were based on the pooling of mean data from just nine cohorts using various measurement tools and assumed a linear pattern of change.

More sophisticated statistical techniques are available to measure longitudinal data. The recent development of more advanced statistical modelling tools that take advantage of data sources with repeated measures allows for empirical estimation of the development of certain processes over time.12 Group-based trajectory models are designed to identify clusters of individuals following similar progressions of some behaviour or outcome over time.13 Most statistical approaches assume linear relationships of variables over time but this may not necessarily be the case. Trajectory models also allow exploration of non-linear changes in symptoms that might, for example, be more rapid initially or less rapid at later stages.

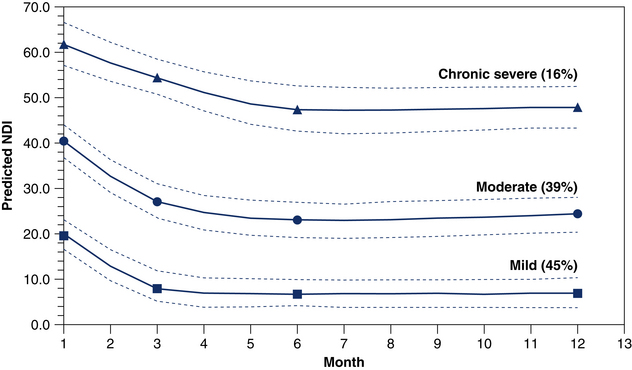

Using these types of analyses, a recent study demonstrated a general pattern of decline in pain/disability levels (measured with the Neck Disability Index14) over 12 months following whiplash injury. However, three distinct patterns of predicted recovery (trajectories) were identified (Fig 2.1):

Figure 2.1 Predicted Neck Disability Index (NDI) trajectories with 95% confidence limits and predicted probability of membership (%). Suggested cut-offs for the NDI are: 0–8% (no pain and disability); 10–28% (mild pain and disability); 30–48% (moderate pain and disability); 50–68% (severe pain and disability); and >70% complete disability.16 With permission.

In this study, the majority of injured people were predicted to have some degree of persistent symptoms (55%) at 12 months.15 These findings are consistent with recent systematic reviews that indicate a general decrease in symptoms following injury but that a significant proportion (approximately 50%) of people will have ongoing symptoms at one year post motor vehicle crash (MVC).10

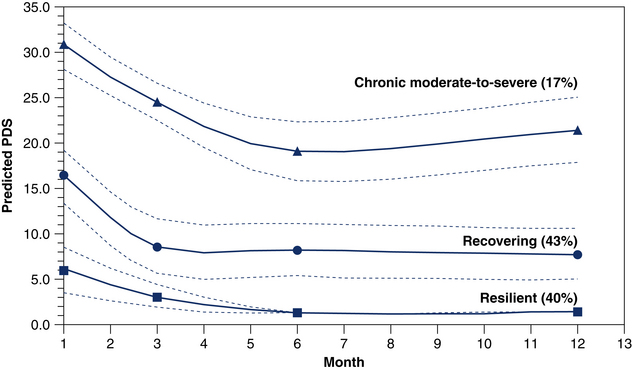

Psychological distress in various forms, such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, depressive symptoms and pain-related distress,17–19 are also commonly reported by those with acute and chronic whiplash; these are discussed in depth in Chapter 8. However, few studies have documented the psychological recovery pathways following injury. In the study described above, trajectory based modelling was also used to identify recovery pathways for symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using the symptom severity score of the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS).20 It was demonstrated that 40% of whiplash-injured individuals were estimated to show psychological resilience to the injury, while 43% were estimated to have initial moderate PTSD symptoms declining to subclinical levels by three months and 17% showed persistent moderate-to-severe symptoms for at least 12 months (Fig 2.2). The symptom severity score of the PDS was used in the analyses, but this tool also yields a PTSD diagnosis if specific criteria are met following a minimum period of one month post injury.20 In this study, at three months post MVC, 22.3% of participants met the criteria for a probable PTSD diagnosis, with this percentage decreasing to 17.1% by 12 months. These data are interesting in that they are similar to that documented for people with more severe traumatic injury that required hospitalisation or admission to intensive care21 and are somewhat unexpected for whiplash, which is considered a more ‘minor’ injury.

Figure 2.2 Predicted PDS trajectories with 95% confidence limits and predicted probability of membership (%). Suggested cut-offs for the PDS total symptom severity score are: 0 no rating, 1–10 mild; 11–20 moderate; 21–35 moderate-to-severe; and ≥36 severe.22 With permission.

Inspection of these trajectories (Figs 2.1 and 2.2) also reveals that most recovery, if it occurs, takes place in the first two to three months following the initial injury, with the condition plateauing after this time. These data are in agreement with those of a recent systematic review11 and indicate the importance of management in the acute/subacute stage in order to prevent the development of a chronic pain condition. The exception to this is the chronic moderate-to-severe PTSD trajectory where there appeared to be a worsening of symptoms at around six months. It is likely that individuals who may follow this trajectory will require specific psychological intervention to prevent this course. Such management approaches are often not provided to people with whiplash.23, 24

Physical and psychological characteristics

Most whiplash-injured people who present for treatment will display some physical and psychological signs associated with their neck pain condition. These are commonly in the form of decreased range of neck movement, local hyperalgesia over the cervical spine and possibly some psychological distress.25 Approximately 20–30% of those injured will display a more complex presentation comprising: sensory disturbances such as allodynia and widespread hyperalgesia in the neck region but also at remote sites such as the lower limbs; spinal cord hyperexcitability via heightened flexor withdrawal responses; more marked loss of neck movement; motor control deficits, including altered patterns of muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder girdles; and greater levels of psychological distress.23 Readers are referred to Chapters 5–8 for a detailed discussion of these characteristics and their assessment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree