1 Clinical History and Examination

Cases relevant to this chapter

6,11,13,16–22,24–25,28–31,33–34,37,49,51,55–56,66,68–71,73–76,78–79,82–85, 87–88,91,93,96–97,100

Essential facts

1. A diagnosis of a musculoskeletal condition can usually be made from a good history and a systematic examination of joints, spine and limbs.

2. The proximal and adjacent joints to the joint under consideration need to be included in the examination, because pain in one joint may be referred from pathology in other joints.

3. Red flag symptoms include: pain preventing sleep; loss of appetite; loss of weight; temporal headache and blurred vision; loss of bladder/bowel control; and rapidly progressive symptoms.

4. Red flag signs include: ‘drawn’ facial appearance; saddle anaesthesia; bilateral limb neurology; upper motor neurone signs; painful swelling; fever >38°C; inability to weight-bear; or a red, hot joint.

5. Malignant tumours of bone and soft tissues are typically rapidly growing, over 5 cm in size, painful, and deep to the deep fascia.

General considerations

History

1. Do you have any pain or stiffness in your muscles, joints or back?

2. Can you dress yourself without difficulty?

If all three replies are negative, the patient is unlikely to have a significant musculoskeletal problem.

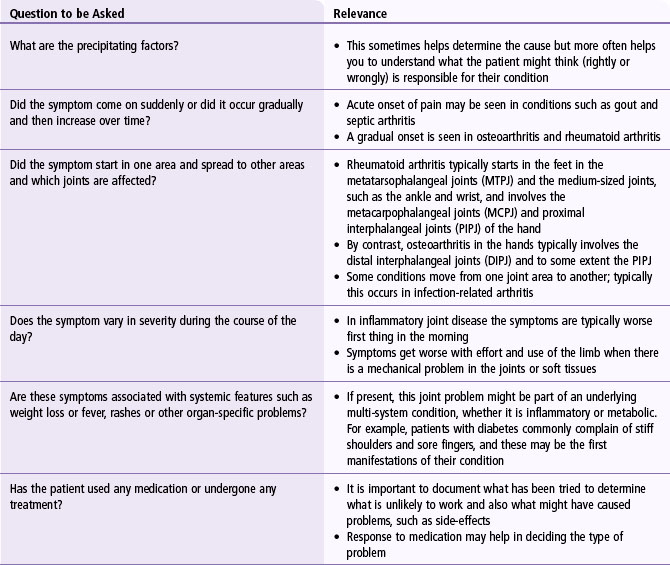

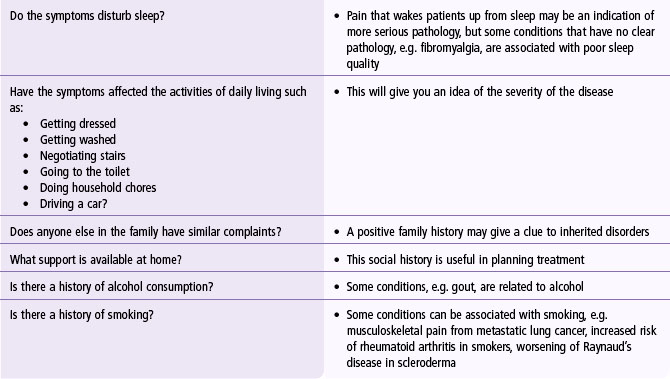

The common symptoms that patients may present with include pain in the limb, deformity, limitation of joint motion or joint stiffness, and weakness of the limb. It is important to ask questions pertaining to these symptoms to establish a working diagnosis of the underlying condition. The common questions that need to be asked and the relevance of these questions are shown in Table 1.1.

‘Red flags’ in non-traumatic disorders

On the beach, never swim where a red flag is flying; a danger to life exists. In medicine, never ignore a ‘red flag’ symptom or sign: a danger to life or limb exists. These clinical features are shown in Table 1.2. Emergency diagnoses in the locomotor system and the danger to which attention is drawn are listed in Table 1.3. Clinicians frequently misdiagnose rare but dangerous conditions. In the early stages of such disorders, the clinical features may be similar to more common self-limiting conditions. Later, there is no excuse for missing an obvious swelling.

Table 1.2 Clinical ‘red flag’ features suggesting serious pathology

| Symptom | Corresponding Sign |

|---|---|

| Pain preventing sleep | ’Drawn’ facial appearance |

| Loss of appetite | Loss of weight |

| Temporal headache and blurred vision | Visual loss |

| Loss of bowel and bladder control | Saddle anaesthesia, bilateral lower limb neurology |

| Other signs | |

| Rapidly progressive symptoms | Bilateral upper motor neurone signs |

| Painful swelling | Fever >38°C |

| Red, hot swollen joint | Inability to bear weight through a joint |

Table 1.3 Emergency diagnoses and dangers in musculoskeletal patients

| Diagnosis | Danger |

|---|---|

| Tumour | Loss of life or limb |

| Infection | Bone or joint destruction |

| Central cord compression | Limb/bladder/bowel dysfunction |

| Cauda equina syndrome | Bladder/bowel dysfunction |

| Giant cell arteritis | Blindness |

| Slipped upper femoral epiphysis | Early hip arthritis |

Malignancy

These lesions should be viewed as a potential malignant tumour until proven otherwise. Even one or two of these features should provoke early investigation. A delay of weeks will compromise treatment options and survival.

Infection

As in potentially malignant tumours, even one or two of these features should provoke early investigation. A delay of hours or days will lead to established infection, with bone or joint destruction and more extensive surgical reconstruction required later.

Spinal disorders

• presentation under age 20 or over age 55 years

• past history of carcinoma, steroids, human immunodeficiency virus

• widespread neurological symptoms

Signs of an ‘upper motor neurone’ lesion indicating central cord compression include hypertonic weakness and rigidity, brisk reflexes and sustained clonus. Causes include spinal infection (pyogenic or tuberculosis), tumour, cervical vertebral subluxation secondary to trauma or rheumatoid arthritis, or a cervical or thoracic central disc prolapse. Symptoms of sphincter and gait disturbance with saddle anaesthesia are highly suggestive of cauda equina syndrome, requiring an urgent magnetic resonance imaging scan for confirmation of central disc prolapse and appropriate urgent spinal decompression.

Examination of limbs

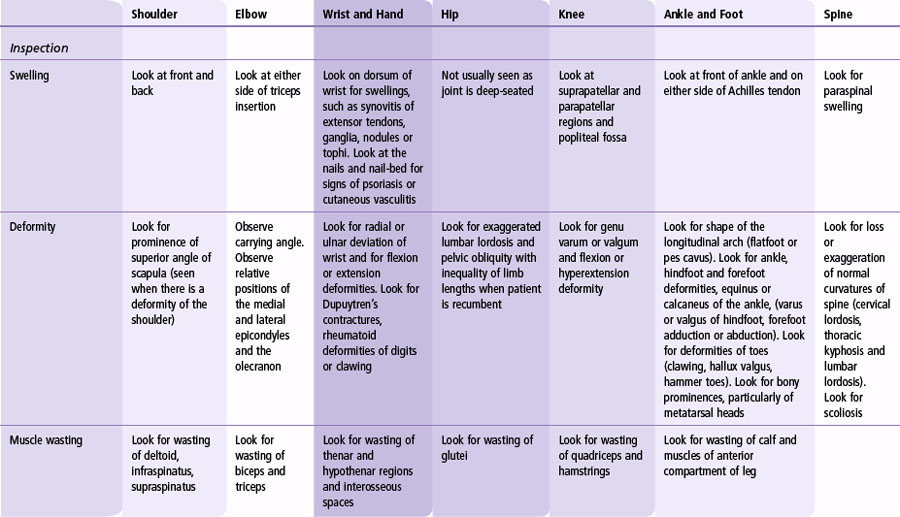

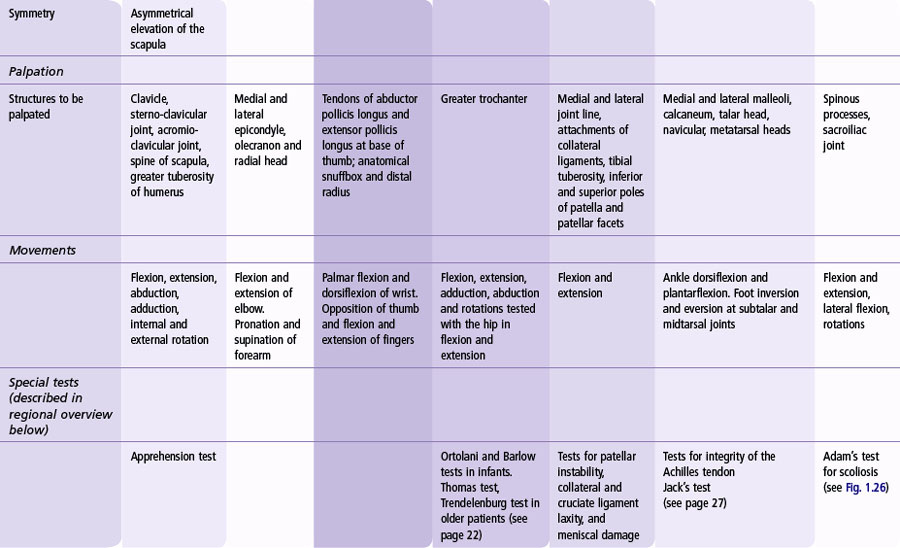

A good general format of examination of the musculoskeletal system is the GALS (gait, arms, legs and spine) method to ensure that the entire musculoskeletal system is included in the examination. For each individual joint examination it is best to adopt a systematic approach using ‘Look, Feel, Move and Special Tests’ as outlined below (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4 Important points to observe in joints during clinical examination

| Look | Scars, sinuses, swelling, deformity and erythema |

| Feel | Skin, soft tissues and joint |

| Move | Active and passive; normal range, reduced or increased range of movement; and stress tests |

| Special imaging (see Chapter 4 on Imaging) | Plain X-rays are the mainstay |

| MRI gives good definition of non-osseous structures | |

| Ultrasonography is useful for joint effusions and rotator cuff tears of the shoulder | |

| Arthrography is used to confirm reduction of a hip in a child |

Look

• Nodules (e.g. rheumatoid nodules)

• Skin rashes or lesions (e.g. psoriasis)

• Scars of previous surgery, trauma or infection

• Asymmetrical or symmetrical abnormalities (symmetrical involvement seen in rheumatoid arthritis).

Feel

• A difference in temperature in and around the joint. Use the back of your hand to assess temperature; feel proximal and distal to the potentially abnormal area. There is usually a temperature gradient away from the heart so that the thigh is normally warmer than the knee, which is warmer than the shin. The back of your hand is very sensitive to these graded temperature changes and you should apply this evaluation routinely when examining large joints such as the knees.

• Tenderness – you should look at the patient’s face while palpating:

• Swelling, which you will have detected on inspection. Feeling for swelling at this stage would confirm what you have seen, but also determines the nature of the swelling. You want to know whether it is fluid, soft tissue or bone. Massaging a joint may be a good way of detecting fluid within a joint, but remember that very swollen joints will fail this test because there is nowhere for the fluid to go.

Move

You then need to test the movements of the joint.

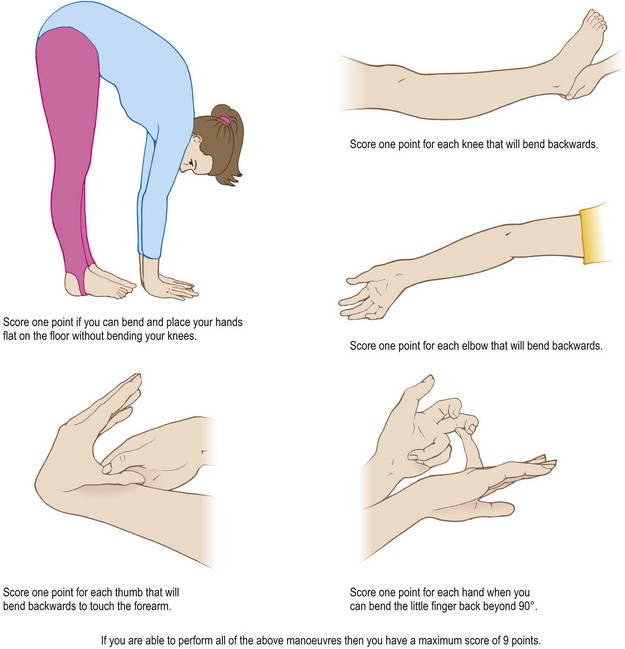

Active movement, i.e. that performed by the patient, should be observed first followed by passive movement performed by the examiner. If the patient has an excessive range of movement, this could suggest that they are hypermobile (Fig. 1.1) or that the capsule and ligaments have stretched and become ineffective in maintaining stability of the joint. If the active range of movement is restricted this may be due to pain, weakness, loss of neurological function, tissue stiffness, contracture or bony changes, such as ankylosis (fusion of a joint).

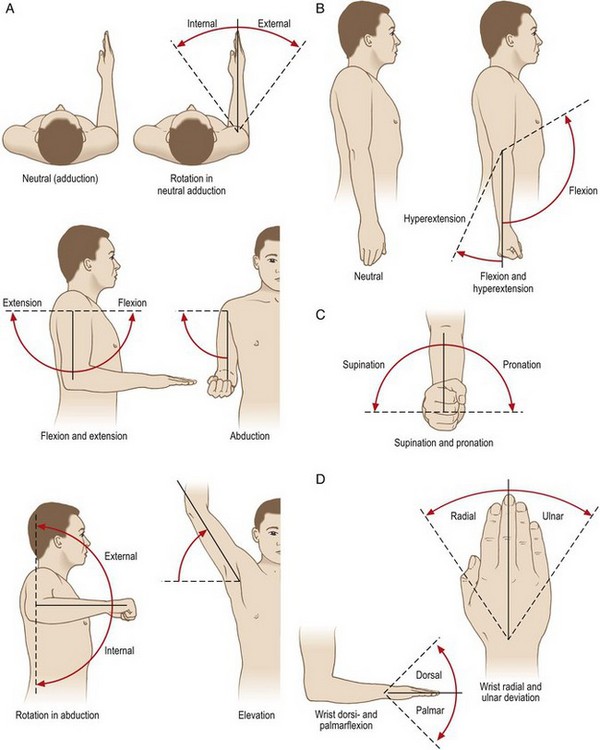

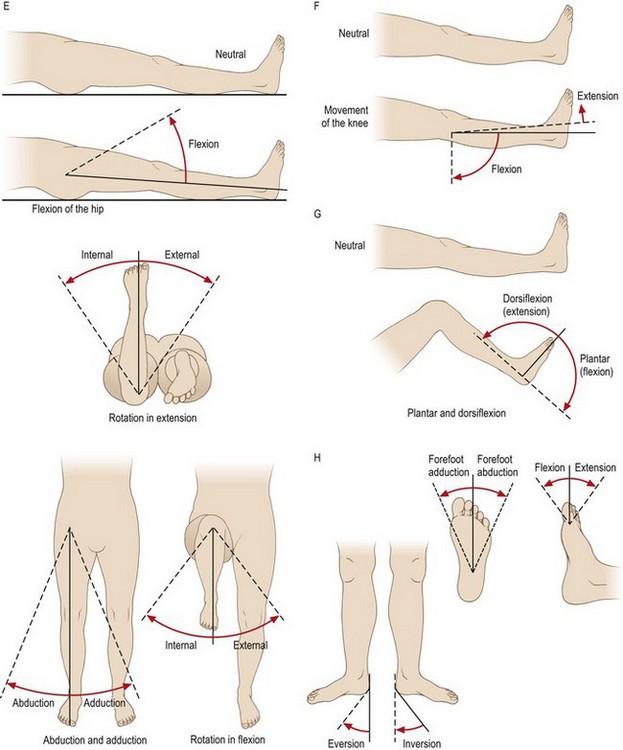

The main benefit of checking passive movement is that, if weakness or stiffness is a limiting factor, you can assess the full range of joint movement with assistance. Measure the range of passive movement and express it in degrees using the Debreunner notification. The range of motion may be normal, reduced or excessive. The normal range of movements is shown in Figures 1.2 and 1.3. For example, elbow motion:

• In a normal person is expressed as: 0 – 130° (0° extension and 130° flexion)

• In a person with 10° of hyperextension is expressed as: 10 – 0 – 130°

• In a person with 10° of fixed flexion deformity is expressed as: 10 – 130°

Make a note of the quality of movement (i.e. is it associated with pain or crepitus?)

• If there is pain on movement, determine at what point of movement pain is experienced

• Place the palm of your hand over the joint that is being moved to feel for crepitus.

Shoulder

Overview of anatomy and examination

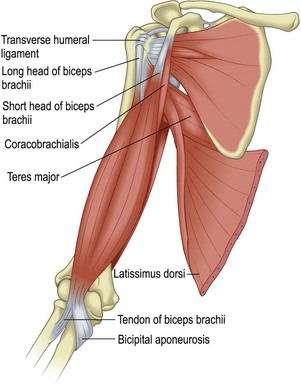

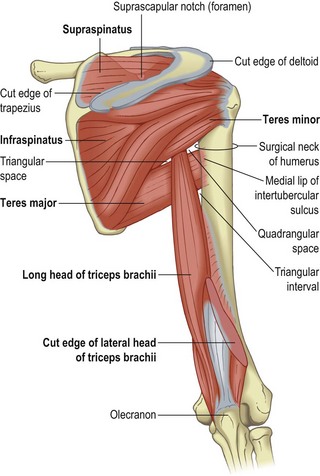

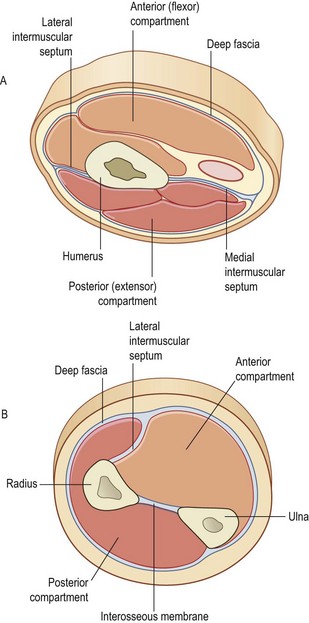

The muscles of the arm comprise biceps, coracobrachialis and brachialis anteriorly, and triceps posteriorly. Coracobrachialis flexes the arm at the shoulder joint; biceps flexes the elbow and supinates the forearm, and also contributes to flexion of the arm at the shoulder joint. Brachialis is a powerful flexor of the forearm at the elbow. Figures 1.4 and 1.5 show the details of muscle attachments of the arm and Figure 1.6 shows these areas in cross section.

FIGURE 1.4 Anterior muscles of the shoulder and arm

(Drake R, Vogl W, Mitchell A. Gray’s anatomy for students. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; 2004)

FIGURE 1.5 Posterior muscles of the shoulder and arm

(Drake R, Vogl W, Mitchell A. Gray’s anatomy for students. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; 2004)

FIGURE 1.6 Cross-sections of the upper arm (A) and forearm (B)

(Drake R, Vogl W, Mitchell A. Gray’s anatomy for students. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; 2004)

A painful arc exists if the patient experiences pain when abducting the shoulder between 90° and 120°. Loss of active gleno-humeral abduction may indicate a tear of the rotator cuff. The muscles of the rotator cuff can be tested individually. For subscapularis, ask the patient to put their hand behind their back and internally to rotate the shoulder against resistance. This may not be possible if the shoulder is stiff and, alternatively, the muscle can be tested by internal rotation of the forearm against resistance, keeping the elbow flexed at 90° and the shoulder in a neutral position. For supraspinatus, test abduction of the shoulder against resistance beginning with the arm by the patient’s side to remove the abductor action of deltoid. Infraspinatus and teres minor, both of which act as external rotators, can be tested by asking the patient to hold their arm at 30° of flexion and then externally rotate the shoulder against resistance. This position removes the contribution of deltoid as an external rotator. Pain rather than weakness during these manoeuvres would suggest that the patient may have a rotator cuff tendonitis rather than a tear. A painful arc of movement of the gleno-humeral joint may help to distinguish between inflammation and a tear (see Chapter 21).

Elbow

Overview of anatomy and examination

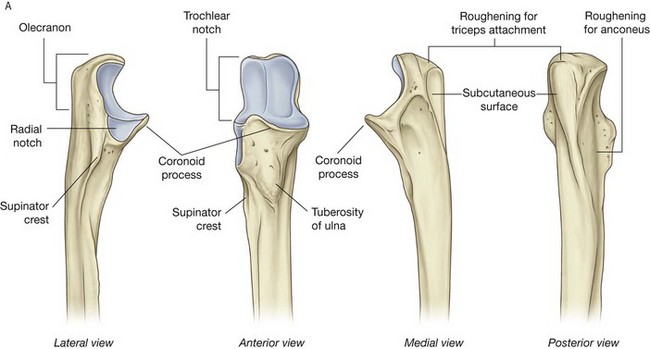

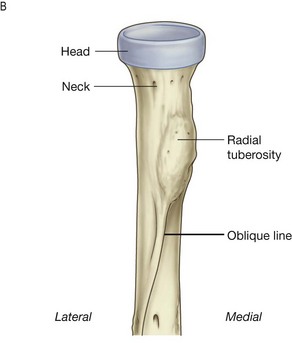

Although there are three joints (humero-ulnar, humero-radial and radio-ulnar) in the elbow sharing a common synovial cavity, the elbow should be considered as a hinge joint producing extension and flexion. Figure 1.7 shows the anatomy of the elbow.

FIGURE 1.7 Anatomy of the elbow

(Drake R, Vogl W, Mitchell A. Gray’s anatomy for students. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; 2004)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree