, James B. Galloway2 and David L. Scott2

(1)

Molecular and Cellular Biology of Inflammation, King’s College London, London, UK

(2)

Rheumatology, King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

A number of clinical and laboratory methods have been developed to measure both the disease activity and severity of inflammatory arthritis patients. The most frequently used clinical measure to assess arthritis activity is joint counts (counting the number of swollen and tender joints, usually in 28 pre-specified joints). These are often combined with other clinical and laboratory measures in a composite score called the disease activity score on a 28-joint count (DAS28). Many measures of assessing inflammatory arthritis severity exist. In clinical practice the commonest methods include X-ray and ultrasound imaging, which capture joint damage and inflammation, and the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), which provides information on function and disability. This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of the methods used to assess the activity and severity of patients with an inflammatory arthritis.

Keywords

Disease OutcomesDisease ActivityJoint CountsRadiographyDisabilityQuality of LifeRole of Assessments

The presence of an inflammatory arthritis is relatively easy to diagnose. The presence of painful, swollen joints is usually self-evident to both patients and clinicians. However, dividing patients into specific diagnostic groups can be challenging. Equally difficult is determining changes in the severity of arthritis over time. Clinical and laboratory assessments are vital to making informed decisions about diagnosis classification and disease severity.

Assessments used in patients with arthritis include joint counts, assessments of global health, patient self-assessments of disability and quality of life, laboratory assessments of disease activity and autoantibody status and imaging assessments of joint inflammation and joint damage [1]. Often a number of these various assessments are linked together to give composite scores of disease activity.

Clinical Assessments

Joint Counts

The characteristic features of inflamed joints comprise swelling and tenderness [2]. Joint swelling is soft tissue swelling detected along joint margins. When there is a synovial effusion, a joint is inevitably swollen. Effusions are not however mandatory features of a swollen joint. The most characteristic feature of a swollen joint is fluctuation, in which fluid can be displaced by pressure in two planes.

Bony swelling and joint deformities often complicate the counting of swollen joints. Neither of these indicates the presence of joint swelling, although they can be present when joints are swollen. In late disease it is often difficult to differentiate swollen from deformed inactive joints.

Joint tenderness is indicated by inducing pain in a joint at rest with pressure. Judging the correct amount of pressure to elicit tenderness depends on both the examiner and the patient. Generally sufficient pressure should be exerted by the examiner’s thumb and index finger to cause ‘whitening’ of the examiner’s nail bed; this equates with a pressure of approximately 4 kg/cm2. In some joints, like the hip, tenderness is best identified through movement.

Many joints can be involved in inflammatory arthritis. Their size and distribution varies substantially, making it difficult to know how best to summate counts. A number of different joint counts have been devised. Initially developed counts assessed all 86 peripheral joints. For many years 66 joints were counted, including the joins in the feet. Currently joint counts usually assess 28 peripheral joints and exclude those in the feet.

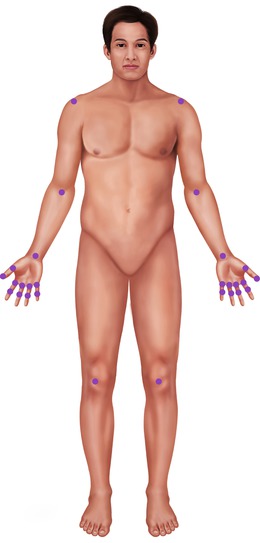

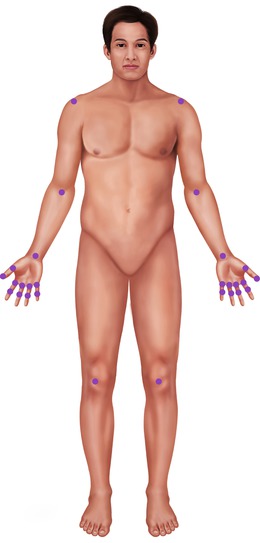

When 28 joints are counted there are different assessments of swollen joints and tender joints. The joints assessed are shown in Fig. 4.1 and comprise:

Figure 4.1

Joints assessed in 28 joint counts

10 proximal interphalangeal joints

10 metacarpophalangeal joints

2 wrist joints

2 shoulder joints

2 elbow joints

2 knee joints.

There are two limitations of using 28-joint counts. Firstly, they imply all joints are identical. However, joints like the knee are substantially larger than some of the interphalangeal joints. Although this can be addressed by correcting the count for the size of the joint involved, such corrections are rarely undertaken. Secondly, they ignore joints in the feet, and these can often be active when the hands are uninvolved. Nonetheless the 28-joint count is as effective as all other approaches.

There is no exact number of swollen or tender joints that mean arthritis is active. However, most experts suggest that 6 swollen and 6 tender joints indicate active disease and none or one swollen and tender joints represent low disease activity or remission.

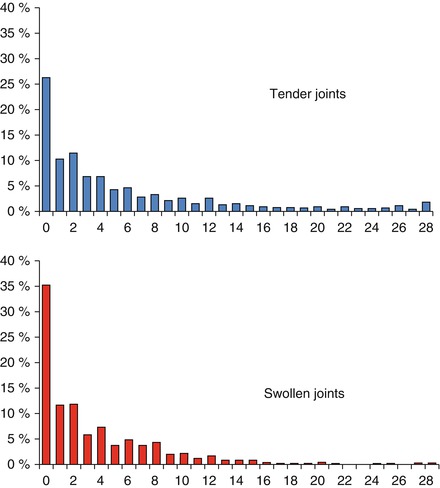

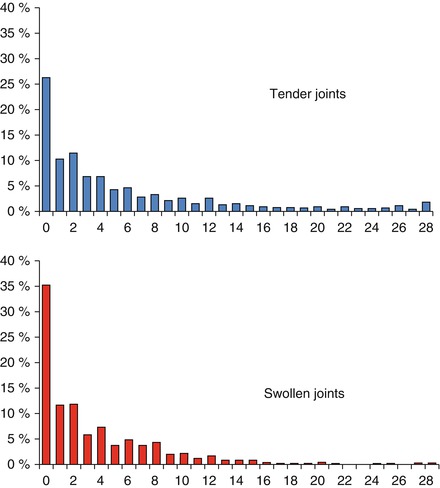

Examples of tender and swollen joint counts in 1,712 patients with RA attending our clinics are shown in Fig. 4.2. Only a few patients have many active joints. Most patients have no active joints or only one or two tender and swollen joints. In addition the number of tender joints is somewhat greater than the number of swollen joints.

Figure 4.2

Joint counts in 1,712 patients with rheumatoid arthritis seen at King’s College Hospital, London

Global Assessments

Global or overall assessments by patients and by clinicians are often used to assess disease activity. They are conventionally recorded using visual analogue scales (VAS). These score responses on 100 mm scales. Descriptive Likert scores have also been used; these group responses into distinct categories. Typically there are five categories which range from strongly agree to strongly disagree. High scores by patients and clinicians represent active arthritis.

One issue is which clinician should assess patients. Specialist rheumatologists, specialist nurses and allied health professionals, and a range of different healthcare professionals can all be involved. Their views are not entirely comparable. There is no correct answer and the range of assessments can be instructive and relevant.

The subjective nature of global assessments limits their overall value in determining disease activity. Some observers are optimistic while others are pessimistic. This makes comparisons between patients and observers less useful than changes over time within one individual’s observations.

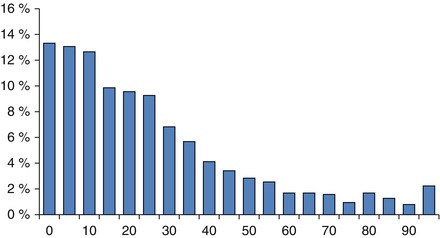

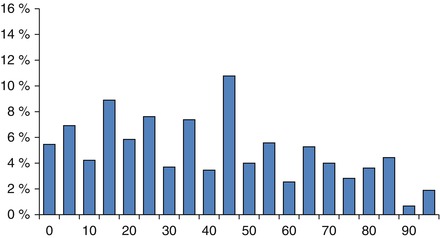

Examples of patient global assessments in 1,712 patients with RA attending our clinics are shown in Fig. 4.3. There is a wide range of different levels of response in patients. Unlike joint counts, which are distributed to the left side, there is a relatively even distribution of patient global responses across the whole range of possible scores. This indicates that patients’ views of their arthritis are somewhat different from the objective assessments made by clinical assessors.

Figure 4.3

Patient global assessments in 1,712 patients with rheumatoid arthritis seen at King’s College Hospital, London

Pain Scores

Pain is usually considered to be a ‘subjective’ measure because its assessment is based on data obtained from the patient, which contrasts with ‘objective’ data from physical examination and laboratory tests [3]. However, quantitative estimations of levels of pain can only be obtained from patients and there is no alternative source.

There are a variety of ways of assessing pain. All of these are based on patient self-reported pain. The simplest approach, which is suitable for both research and routine practice, is to use a VAS. The standard VAS is a 10-cm scale bordered on each side. At the ‘0’ mark, it says ‘No pain at all’, and at the ‘10’ mark, ‘Pain as bad as it could be’. Pain is then recorded as the length in millimetres from the zero mark on the scale.

An alternative is to use categories of pain. These provide five or more categories. For example none, minimal, moderate, severe and very severe. Such simple categorical scales are known as Likert scales. Both VAS and Likert scales provide similar information, but the Likert scales are less often used.

Pain is recorded within composite health status measures like the SF-36. There are also more complex pain scores that can be used in arthritis. An example is the McGill Pain Questionnaire. These are restricted to research studies.

There are several practical problems in using pain VAS scores. Firstly, they are better at measuring short term changes in pain. Patients have difficulties retaining any memory of pain severity over months or years. Secondly, they are influenced by the way patients complete VAS scores. Some patients use the full scale while others are more restricted and use only a small region of the scale. This makes it difficult to compare one patient’s pain scores with another; the scores are better at defining changes in individual patients. Finally, some patients feel pain with a minimal stimulus compared to others. This is the concept of pain thresholds. Pain scores are usually high in patients with low pain thresholds and vice versa.

Functional Assessments

Function can be measured using “objective” measures of observed performance, but this approach has largely been abandoned in favour of assessments based on self-completed questionnaires that record patients’ perception of their function.

The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) is the most widely used self-completed questionnaire to assess disability. It was developed over 30 years ago at Stanford. It focuses on self-reported, patient-oriented outcome measures [4].

HAQ assesses upper and lower limb function related to the degree of difficulty encountered in performing a number of specified daily living tasks. It assesses eight different domains of function. Each of these is scored on a range of zero to three. These indicate tasks can be undertaken without any difficulty (zero) or the patient is unable to do them (three). The highest score in each domain is used to calculate the overall HAQ score. The domains comprise dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and chores or activities

The scores from these eight domains are added to create a 0–24 point score which is then reduced to a 0–3 scale by dividing by eight. A HAQ score of zero 0 represents no disability. A score of 3 represents very severe disability and high dependency. HAQ scores can be measured in a range of different languages.

The reason for creating a 0–3 scale is historical. It allowed HAQ scores to be related to the initial functional score, which used a scale of I-IV grading for function; I was normal and IV completed disabled. A HAQ score of zero was linked to a functional grading of I and a score of 3 to a functional grading of IV. HAQ superseded the four-point functional score because it was better able to detect small changes in function.

HAQ is a very useful assessment but it has some limitations. One problem is that there are floor and ceiling effects. This means that low levels (floor) and high levels (ceiling) of disability are not recorded accurately by HAQ scores. This is a problem in applying HAQ to diverse groups of patients. In patients in the community with low levels of disability HAQ does not fully capture their problems. It also has limitations in assessing highly disabled patients from specialist centres with multiple problems.

Another specific problem in measuring disability is that HAQ scores are not linear. Although HAQ looks like a simple number line, it does not perform as one. A change from zero to one is not the same in terms of its impact on an individual patient as a change from 2 to 3.

A third limitation is that the change in HAQ scores that produce clinically noticeable changes from the perspective of individual patients is relatively high. Most experts believe a change in HAQ scores of 0.22–0.25 is required for patients to notice a difference in function. This means that the score is acting at the margin of detectable change as most drug treatments produce this level of change compared to placebo therapy.

A final problem is patients’ perceptions of disability change as their arthritis progresses. In early arthritis HAQ scores can be high whilst in later disease they can be lower. The initial high HAQ scores in early arthritis improve when patients receive effective treatments. They then increase slowly as there is loss of muscle strength and a general increase in joint damage. But the increases are very slow and along the way patients change their perception of disability. In addition, with advancing age all people show some increase in disability due to the effects of aging.

Many other functional assessments have been used in arthritis. These include the Arthritis Impact Score and the Lee functional index. None of these have achieved the wide usage of HAQ scores.

Generic Health Status Measures

A number of generic health status measures are sometimes used in arthritis [5]. These include the SF-36, the Nottingham Health Profile and the EuroQol. The SF-36 and EuroQol are the dominant measures. Though they are rarely used in clinical practice, they have important research roles. Unlike disease specific assessments, they can be applied in all diseases and health states. They can therefore help compare the impact of arthritis with that of other medical disorders.

SF-36

The SF-36 is the dominant health state measure. It has been developed over 25 years and is available in almost all languages. It assesses health in 8 domains to give an overall health profile. Unlike most other measures zero represents poor health and 100, the upper end of each scale is perfect health. The SF-36 can be divided into two broad subscales assessing physical health and mental health. These are the physical summary scale and the mental summary scale.

The eight subscores assess physical function (2 scales), pain, vitality (broadly equivalent to fatigue), global health, social function and mental health (2 subscales).

Like HAQ there are problems with ceiling and floor affects and the SF-36 is relatively insensitive to measuring change in arthritis [6]. However, it provides a powerful picture of the overall impact of arthritis, which extends far beyond effects on physical function and pain alone. SF-36 scores in arthritis can be compared to scores for normal populations defined by age and sex and also by country.

EuroQol

The EuroQol, which is also known as EQ-5D, is a simpler measure that attempts to assess health status on a single line from zero (equivalent to death) to one (equivalent to complete health). It asks questions across a series of five domains. The questions are rather simple and the scoring is complex so that some health states score below zero, which is effectively worse than dead. The measurement properties of the EuroQol make it relatively unhelpful in arthritis. However, as it is often used in health economic studies and its overall importance in rheumatic diseases should not be underestimated.

Laboratory Assessments

Quantitative laboratory markers like the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are useful for monitoring because they are a consequence of systemic disease. Qualitative markers like RF indicate prognosis and may have pathogenic relevance.

Acute Phase Response

Inflammation in the joints as elsewhere involves a systemic reaction as well as a local reaction. The systemic reaction is often termed the acute phase response. It can be measured in many different ways. However, the main tests are the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and the C-reactive protein (CRP). Serum amyloid A protein tests are more sensitive but are rarely used due to technical limitations in the immunoassay method.

ESR and CRP levels are closely related to most clinical measures of disease activity [7]. In early arthritis they are mainly related to joint swelling. A persistently elevated acute phase response is associated with high rates of progressive joint damage. They provide more objective measures of disease activity than clinical assessments alone. The acute phase response occurs as a response to many different causes of inflammation. High levels of the ESR and CRP are therefore non-specific features in arthritis.

The ESR is the rate at which red blood cells precipitate in a period of 1 h when anti-coagulated blood is placed in an upright tube. The rate at which blood sediments is measured and reported in mm per hour (mm/h). The ESR reflects the balance between pro-sedimentation factors, especially fibrinogen, and factors resisting sedimentation, particularly small charge on the red blood cells. During inflammatory high levels of fibrinogen increases the rate of sedimentation. As the ESR is affected by many different proteins it is a very non-specific test. It is, however, often measured when evaluating the activity of inflammatory arthritis patients. Examples of ESR levels in 1,712 patients with RA attending our clinics are shown in Fig. 4.4. Over half the patients have raised ESR levels; some are very elevated at over 90 mm/h.