14 Client groups

Massage for people with neurological disorders

Slow stroking over the posterior primary rami region, based on the Rood approach, has been advocated by O’Sullivan (1988). Her suggested mechanism for the resulting reduction in muscle tone is activation of the inhibitory reticular system, which temporarily replaces the lost descending inhibition. In a study by Brouwer and Sousa de Andrade (1995), 10 patients with multiple sclerosis had measures taken of H-reflex amplitude, H-reflex amplitude during vibration and Achilles tendon jerk, in the triceps surae muscle. The measurements were taken before, immediately after and 30 minutes after stroking. The technique consisted of 3 minutes of continuous stroking from the occiput to the coccyx (with the patients lying prone), by the therapist’s index and middle fingers on either side of the spinous processes. A significant reduction in H-reflex amplitude was found in the group with multiple sclerosis, particularly 30 minutes after the stroking ended. The study was well controlled except for use of baclofen (an antispastic drug), although analysis showed that subjects taking the drug demonstrated the same trend in results, albeit to a lesser degree. In addition, the subjects reported subjective feelings of relaxation. Farber (1982) suggests that 3–5 minutes should be the maximum length of time this type of massage is given to neurological patients, to avoid rebound effects of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) or skin irritation.

Sirotkina (1964) used massage on flaccid muscles in the hemiparetic arms of stroke patients, in an attempt to increase muscle tone. Electrical activity was shown to increase following massage. Massage has been shown to have a positive psychological effect on multiple sclerosis sufferers. Hernandez-Reif et al (1998) compared ‘medical treatment’ with massage and found that the massage group improved anxiety and depression scores after ten 45-minute massages over 5 weeks.

Massage in respiratory disorders

Massage is not in widespread use with this client group. Asthma and other conditions which cause breathlessness, however, can lead to feelings of panic and anxiety so it may be that massage has a use in assisting patients to manage these conditions. Connective tissue manipulation has been used to reduce bronchospasm. Beeken et al (1998) studied the effects of neuromuscular release massage therapy in five individuals. Four of the subjects had an increase in thoracic gas volume, peak flow and forced vital capacity. The authors report significant improvements in heart rate, oxygen saturation and systolic blood pressure following 24 weekly treatments. These findings are of interest and may be worth repeating with a larger sample to explore whether the findings can be generalised to other individuals, and whether massage was the only causative factor in the improved physiological measures. Massage was found to be superior to relaxation therapy in children with asthma (Field et al 1998a). The children were more relaxed after massage and over time experienced improvement in lung function. It is unclear whether the effects were psychological or physical, as again this research group did not control with another touch therapy. It also had poor reporting characteristics (Hondras et al 2001).

Pain

A study conducted on volunteer healthy subjects found that massage produced hypoalgesic effects on experimental pain (Kessler et al 2006). Weinrich and Weinrich (1990) studied 28 patients with cancer, assigning them to two groups of 14 in matched pairs. The treatment group received 10 minutes of massage (performed by senior nursing students who had received less than 1 hour of massage training), while the control group was visited for 10 minutes. The back massage significantly reduced pain in men but not in women. This was short-term relief, as no significant differences remained after 1 hour. The levels of pain before the massage were, in fact, quite low, so significant falls would have been difficult to demonstrate in a sample of this size.

In a larger study, Marin et al (1991) studied the effect of massage on 116 patients who had had a thoracotomy. A visual analogue scale was used, as in the Weinrich study, and it was found that massage and physiotherapy reduced pain significantly. This is a French paper and unfortunately the English abstract does not give further details. Massage therapy was found to have superior effects to transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), a common treatment for chronic pain, and placebo TENS in fibromyalgia patients. The massage therapy group enjoyed improved sleep patterns and decreased pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression and cortisol levels following ten 30-minute massages over 5 weeks. The TENS group also improved across several parameters by the last treatment. The massage therapy was compared to modalities which were less intensive in terms of touch and direct individual contact, so the psychological effects of massage cannot be differentiated from any physiological effects in this study (Sunshine et al 1996). In a more recent study of the same client group, massage was found to have a positive effect on pain intensity, number of tender points in the neck and upper back region and functional status in fibromyalgia patients. Massage was added to a treatment regimen of heat and exercise and compared with heat, exercise and mobilisations. Neither approach was found to be superior but the sample sizes were small (n = 7) in this study which contained multiple variables (Aslan et al 2001). A randomised controlled trial undertaken by Hulme et al (1999) explored the effects of foot massage on patients’ perceptions of daycare following laparoscopic sterilisation. The mean pain scores following surgery differed between the two groups (foot massage and analgesia compared with analgesia only), with the foot massage group reporting less pain over time, although this was not statistically significant. Field et al (2000) studied the effects of burn scar massage and found that twice-weekly massage reduced the incidence of itching, pain and anxiety and improved mood. Unfortunately, the mechanical effects on the scar itself were not measured. Massage appears to be a promising intervention for pain relief but studies differentiating between the psychological and physiological effects would inform work with this client group.

Plastic surgery

Patients with cancer may be offered reconstructive (‘plastic’) surgery following disfiguring surgery. Massage following mastectomy is advocated by Field and Miller (1992) for reducing the thickening of the scar, facilitating revascularisation and promoting mobility and elasticity of the skin. These authors also describe massage of silicone breast implants to prevent capsular contracture, a common cause of disfigurement. These massage ‘exercises’ are recommended from 24 to 48 hours after operation and should then become a permanent routine for the patient. The implant under the skin is displaced superior and medially to counteract the effects of gravity. Laterally and inferiorally directed movements can be included, but are optional.

Bodian (1969) reported the efficacy of massage following ophthalmic plastic surgery to reduce thickening of scars and keloid formation and to prevent deformity caused by scar contracture. A technique whereby the skin of the eyelid is stretched to full excursion in a direction opposite to the tightening was described. This method, using approximately 20 excursions three times a day, was taught to the patient or parent 2 weeks or more after surgery. Reported results were softening and thinning of the eyelid, smoothing of the scar as underlying adhesions were released and reduction of keloid formation.

Massage with older people

Within the client group termed the young old (65–74 years) and the old (over 75 years) (Rosenberg & Moore 1995), widely varying degrees of physical and mental health can be found. This is not a homogeneous group and, as far as health is concerned, there is no reason to assume they all have health or functional problems. It is noteworthy that about 80% of older people in the UK perceive their health and activity levels to be satisfactory (Partridge et al 1991). Since then, Western society has seen a move towards increased activity, employment and active leisure pursuits in this age group. However, some of the changes associated with ageing can cause physical discomfort, loss of function and psychological change. Collectively these may lead to a loss of coping skills, which means that these elderly people will require varying levels of support to remain independent in their own home, or will require admission to long-term residential care. In both cases, the prime goals of care are to improve or maintain functional abilities for as long as possible and to enhance the quality of life (QoL). These aims are unlikely to prove successful in the long term if adequate attention is not given also to intellectual and emotional function. Thus, it is especially important to view a programme of care holistically and it may then be found that improvement in one function will often be followed quickly by improvement in others.

Although depression is commonplace in the elderly (Gurland & Toner 1982), the therapist should guard against mistaking the symptoms of depression for dementia, which is an organic brain syndrome. A depressed person may appear confused and lack motivation but the condition may be helped by appropriate interventions. Highly developed interpersonal skills are required of the therapist to maximise the possibility of successful treatment. Empathy and an unconditional positive regard are prerequisites to developing a therapeutic relationship which may partially compensate for the social isolation and anxiety caused by a change in the client’s environment.

Personal autonomy—the freedom to make one’s own choices—is largely denied to elderly people in residential care. This frequently engenders a loss of self-esteem and sense of self, which is damaging to QoL and can also affect motivation. It is important, therefore, that clients should be empowered in such a way that they feel that they have some choices. This is pertinent to the therapist when considering massage with this group of clients. It should not be assumed that every elderly person will welcome touch or that it is necessarily appropriate. However, there is a body of opinion which supports the view that some institutionalised elderly and chronically sick people may be tactually deprived (Barnett 1972, Fakouri & Jones 1987). It has been reported that a group of elderly clients with anxiety and depression responded well to hand massage, experiencing feelings of relaxation and an improved sense of well being (Cole 1992). Back massage with conversation has been shown to reduce anxiety in the elderly. Fraser and Kerr (1993) compared back massage with conversation to a conversation-only and a no-intervention group, in a population of institutionalised elderly clients. The results showed a significant difference in the mean anxiety score between the back massage and the no-intervention group; the results approached statistical significance between the back massage and the conversation-only group. Although the sample size was small (n = 21), which makes the validity of the statistics questionable, this study does lend some support to the use of massage as an intervention with anxious elderly clients in residential care.

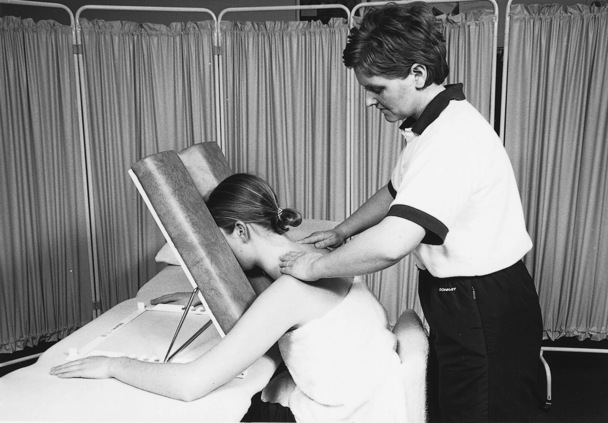

The therapist should ensure that privacy is maintained throughout the massage and require the client to remove only the items of clothing essential for facilitating the treatment. Many elderly people are embarrassed to remove clothing in the presence of another and the therapist will be rewarded if she first takes time to establish a good rapport and remains sensitive to this issue. Care and attention need to be paid to the type of massage administered, particularly in relation to the soft tissues, which are not so resilient as those found in a younger age group. Extra lubricant should be used on dry skin to avoid stretching and uncomfortable friction; light techniques should be used in the presence of fragile blood vessels. The client may not be able to lie in the usual positions for massage: climbing on to a non-adjustable treatment couch may be impossible or unsafe, and for some elderly people the prone position will be uncomfortable. If a treatment couch is used the supine and side-lying positions may be more comfortable, but many clients will require the therapist to use ingenuity in achieving a position that both is effective for the massage and remains comfortable and ergonomically sound for client and therapist (Fig. 14.1). Massage to the upper and lower limbs can be administered with the client seated in a comfortable chair; back massage is facilitated when the client is seated on a stool of suitable height and supported anteriorly by pillows placed on the couch or a table. If positioning is problematic, or if the client does not wish to remove clothing, then a hand massage may be acceptable. This is a useful alternative when privacy cannot be assured and can also be utilised as a component of a group programme for promoting social interaction and shared enjoyment.

Dementia

The therapist must be prepared to take much time in building a relationship of trust with the client and in acquiring the skills needed to communicate in the presence of intellectual and sensory deficits. Several studies support the view that the use of two sensory stimuli during communication are more effective than one, so that the addition of caring touch to a verbal approach may facilitate verbal or non-verbal responses (Kleinke 1977, Langland & Panicucci 1982). The utilisation of touch may not have a universal application: in some patients with high agitation and severe cognitive impairment touch was found to be linked with an increase in aggressive behaviour (Cohen-Mansfield et al 1989). This work supports that of De Wever (1977), who found that nursing home clients often perceived discomfort when an arm was placed around their shoulder by a nurse. Thus, great care should be taken by the therapist to ensure that physical contact is not misinterpreted by the client: ensure that the client is able to observe your approach; attempt to maintain eye contact during communication; always explain what you require from the client; avoid making sudden movements which may startle the client; and, where possible, ensure that the client is in a familiar environment with minimal extraneous sensory distractions. Ballard et al (2002) demonstrated a clinically significant reduction in agitation in patients with severe dementia but these positive effects are attributed to the essential oil melissa. This is regarded as a good study (Thorgrimsen et al 2003).

Massage of the hands may help to accustom the client to being touched, assist in building trust and promote relaxation. Poon (1991) found a 40% increase in self-reported relaxation scores after elderly clients with dementia were treated with hand massage. When the massage was combined with music, the scores increased to 60%. Hand massage may be taught to the family, carers and significant others of dementia sufferers; these are people who often feel helpless in the face of the unremitting nature of the disease and the difficulties in communicating with their loved one. Giving a massage may enable them to enjoy a form of caring touch once again.

Key points

Massage in occupational health

• Stress: work pressure, financial;

• Anxiety: job insecurity, workload;

• Relationships: inside and outside work;

• Environment: abnormal or fluctuating temperature, noise, dust, poor light, cluttered floor can all act as dangers or stressors;

• Unergonomic design of the workplace or task;

• Static loading on the musculoskeletal system;

• Moving and handling of excess or awkward loads; and

The most common musculoskeletal problems for which a physiotherapist is consulted are spinal pain and work-related upper limb disorders (WRULDs), otherwise known as cumulative trauma disorders. The latter includes the controversial repetitive strain injury (RSI). The mechanisms that produce the symptoms of RSI are poorly understood (Pheasant 1992) and therefore its recognition by the medical profession remains inconsistent. It is of interest that the symptomology can exist when repetitive strain is not a feature of the job.

Symptoms occur primarily in the soft tissues and may be diagnosed as carpal tunnel syndrome, tenosynovitis or tennis elbow, which are thought to be due to overuse (as in tennis elbow), repetitive friction between the tendon and its sheath (tenosynovitis) and fluid pressure build-up with resultant nerve pressure in a confined space (as in carpal tunnel syndrome). The latter is more likely in pregnancy when fluid retention can be a causative factor. However, in many work-related problems, while the symptoms may be local, the problem is often more complex. Symptoms and signs are often more diffuse, with discomfort felt at several sites. Thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system often reveals signs proximal to the site of discomfort. It is thought that this is often due to adverse neural tension (ANT) induced by postural factors, muscular tension or previous trauma, either instantaneous or cumulative. Therefore screening for ANT is essential in the treatment of WRULDs (Pheasant 1994). Massage can be used to reduce and prevent some of the contributing factors, and to reduce soft tissue symptoms.

Useful strokes for reducing effects of static muscle work

Massage can also be used to reduce some of the physiological effects of stress and, by promoting a feeling of well being, may help to reduce stress itself. Relaxation massage can contribute to the promotion of good health, a point being addressed in some larger companies to assist workers in maintaining fitness and the flexibility necessary to carry out their work safely and efficiently, thus reducing sick leave costs. Aromatherapy may be the treatment of choice here due to the multisensory effects of massage with essential oils. The therapeutic properties of oils such as geranium and lavender can be utilised to promote relaxation. Field et al (1997a) found that a variety of relaxation therapies, including massage, were equally effective in decreasing anxiety, depression, fatigue and confusion scores in 100 hospital employees. The same research group found massage therapy reduced anxiety, but also enhanced electroencephelogram patterns of alertness and speed and accuracy of mathematical computations (Field et al 1996a). This is interesting as it suggests that relaxation need not induce a drowsy state, but may instead produce alertness. Further work is needed to assess whether different types of massage or different body areas may influence the state of alertness. This study also demonstrates that improved psychological parameters improve work performance, as well as lead to improved well being; therefore initiatives to improve the health of workers are likely to be cost-effective.

Strokes for treatment of work-related problems

Any interruption of typical muscle work patterns is beneficial and health promotion or rehabilitation initiatives are most likely to succeed if they have a good cost–benefit ratio for the client, whether an individual employee or company. This has led to the development of on-site services, pioneered in the USA, where workers are given massage through their clothing without leaving their workstation. Where possible, however, workers are best encouraged physically to leave their workstation as the change of position and the walk, however brief, will be therapeutic and biomechanically beneficial. Levoska and Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi (1993) found that muscle training was more effective than heat, massage and stretching in reducing symptoms of cervicobrachial disorders in 47 female office employees, although the incidence of headache was significantly less at 12 months’ follow-up in the group receiving passive physiotherapy. This illustrates the need for a combined approach. However, seated massage through clothing can be helpful where privacy is not available (see Fig. 14.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree