Abstract

Introduction

The pharmacological treatment of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) pain remains challenging despite new available drugs. Such treatment should always be viewed in the context of global pain management in these patients. To date few clinical trials have been specifically devoted to this topic, and the implementation of treatments is generally based on results obtained in peripheral neuropathic pain. The aim of this review is to present evidence for efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in SCI pain and propose therapeutic recommendations.

Material and methods

The methodology follows the guidelines of the French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SOFMER). It includes a systematic review of the litterature which is performed by two independent experts. The selected studies are analysed and classified into four levels of evidence (1 to 4) and three grades of recommendations are proposed (A, B, C). The review is further validated by a reading committee.

Results

The efficacy of pregabalin has been confirmed in neuropathic pain associated with SCI (grade A). Gabapentin has a lower level of evidence in SCI pain (grade B) but a grade A level of evidence for efficacy in peripheral neuropathic pain. Both drugs can be proposed as first line therapy and are safe to use. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can also be proposed first line (grade B for SCI pain associated with depression, grade A for other neuropathic pain conditions), especially in patients with comorbid depressive symptoms. Tramadol can be proposed alone or in combination with antiepileptic drugs if the pain has a predominant non-neuropathic component. If these treatments fail, strong opioids can be proposed as second/third line (grade B in SCI, grade A in other types of neuropathic pain). Lamotrigine may also be proposed at this stage, particularly in patients with incomplete SCI associated with allodynia (grade B). In refractory central pain, cannabinoids may be proposed on the basis of positive results in other central pain conditions (e.g. multiple sclerosis). Intravenous ketamine and lidocaine can only be proposed in specialized centers. Drug combinations may be envisaged in case of partial response to first or second line therapy.

Conclusions

Very few pharmacological studies have dealt specifically with neuropathic pain related to SCI. Large scale studies and trials comparing several active drugs are warranted in SCI pain.

Résumé

Introduction

Le traitement pharmacologique des douleurs neuropathiques des blessés médullaires reste très difficile malgré l’arrivée de nouvelles molécules sur le marché. Il ne représente qu’une partie des moyens nécessaires à leur prise en charge. À ce jour, peu d’essais cliniques ont été spécifiquement consacrés à ce sujet et la mise en œuvre des traitements se fonde souvent sur des résultats obtenus dans le champ des douleurs neuropathiques périphériques. L’objectif de ce chapitre est de présenter les preuves d’efficacité et de tolérance des traitements pharmacologiques disponibles et de proposer des recommandations thérapeutiques.

Matériel et méthodes

Le travail suit la méthodologie préconisée par la Sofmer. Celle-ci comporte une revue systématique de la littérature sur le sujet effectuée de manière indépendante par deux experts. Les études retenues sont analysées et classées en quatre niveaux de preuve (1 à 4). Les recommandations sont élaborées selon trois niveau (A, B, C). Le texte final est relu et validé par un comité de lecture.

Résultats

À ce jour, seule la prégabaline a fait la preuve de son efficacité dans les douleurs neuropathiques du blessé médullaire (niveau A). La gabapentine a un niveau de preuve plus faible (grade B) mais une preuve d’efficacité de niveau A dans les douleurs neuropathiques périphériques. Ces deux produits peuvent être proposés en première intention, ce d’autant qu’ils bénéficient d’une bonne sécurité d’utilisation. Les antidépresseurs tricycliques peuvent aussi être proposés en premières intention (niveau B dans les douleurs d’origine médullaire associées à des symptômes dépressifs, mais niveau A dans d’autres douleurs neuropathiques), surtout s’il existe des symptômes anxiodépressifs associés. En cas de composante non neuropathique prédominante, le tramadol peut être proposé, seul ou en association avec un antiépileptique. En cas d’échec de ces traitements, les opioïdes forts peuvent constituer des traitements de recours (niveau B, niveau A dans d’autres douleurs neuropathiques). La lamotrigine trouve également sa place à ce niveau, notamment en cas de lésion médullaire incomplète associée à une allodynie (niveau B). En cas de douleurs réfractaires à ces traitements, les cannabinoïdes peuvent être envisagés sur la base d’études positives dans d’autres douleurs centrales. L’utilisation de la kétamine et de la lidocaïne par voie intraveineuse relève de centres spécialisés. Il n’y a pas lieu de prescrire d’emblée une association de plusieurs médicaments, mais deux classes thérapeutiques peuvent être associées secondairement, cas de réponse partielle à un traitement de première ou seconde intention.

Conclusion

Il existe peu d’études concernant les douleurs neuropathiques chez le blessé médullaire, il est donc nécessaire d’encourager des études comportant des effectifs de patients suffisants et comparant l’efficacité de molécules actives dans cette indication.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain, due to spinal cord injury, remains challenging in spite of new available drugs. Finding the proper treatment is particularly difficult because neuropathic pain in SCI patients is generally associated with various other types of pain, contributing to a poor functioning and a reduced tolerability of pharmacological treatments. The latter are rarely used alone but generally as part of the global management of SCI patients including rehabilitation and psychological support. To date, in spite of an increasing number of clinical trials in neuropathic pain, very few randomized placebo-controlled trials have been specifically devoted to SCI-related neuropathic pain and the implementation of a pharmacological treatment for SCI pain is usually based on results obtained for peripheral neuropathic pain . The aim of this work is to report the evidence for efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in SCI-related neuropathic pain and propose therapeutic recommendations for use in this indication.

1.2

Material and methods

1.2.1

Research strategy

The bibliographical search was systematically conducted on the following databases Medline (1966–2007), Embase (1995–2007) or Cochrane (1995–2007). The keywords were: “spinal cord injury(ies) pain” or “central pain” associated to: “pharmacological treatment” or “randomized controlled trial” or to specific pharmacological treatments/classes (analgesics, NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, amitriptyline, antiepileptic, gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, clonazepam, lamotrigine, valproate, phenytoin, topiramate, opioids, morphine, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol, cannabinoids, tetrahydrocannabinol, baclofen, clonidine). The relevant articles were identified from excerpts in referenced journals (mainly meta-analyses or systematic studies) or book chapters .

1.2.2

Selection criteria

The following selection criteria were used:

- •

any therapeutic study with a level of evidence from 1 to 4 acccording to the French Health Authority (HAS) classification or meta-analysis;

- •

studies aiming at describing the efficacy of treatments on SCI central neuropathic pain (at or below the level of injury). The studies including several neuropathic pain conditions were included provided that they reported specific data on SCI pain or included a large proportion of patients with such pain;

- •

articles in French or in English:

- ∘

publications in journals with a scientific reading committee,

- ∘

treatments with a general mode of administration (oral, transdermal, intravenous…).

Non-inclusions criteria were:

- •

local or loco-regional treatments;

- •

publications not reporting the efficacy of treatments on pain (for example; epidemiological data);

- •

non-neuropathic pain (e.g. pain due to spasticity, visceral pain, musculoskeletal pain) or peripheral neuropathic pain (e.g. radicular pain at level, neuropathic pain above level);

- •

book chapters and abstracts;

- •

clinical studies including less than seven patients or controlled single case studies.

1.2.3

Data analysis and report

For each study the reviewed data included methodology, inclusions and exclusion criteria, number of included patients, dosages used and mode of administration, randomization and blinding method, description of patients dropouts, results on primary and secondary outcome measures and safety profile. Efficacy data included neuropathic pain (at or below level) but also when available neuropathic symptoms (continuous pain, paroxysmal pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia), impact on quality of life, comorbidities (anxiety and depression). The number needed to treat (NNT) (number of patients needed to treat to obtain one responder to the active drug) was calculated for the studies which provided with this outcome. For this calculation, the response to treatment was defined as pain reduced by at least 50% or – in the lack of such information – by the number of patients reporting at least a moderate improvement. Studies were classified into four levels of evidence according to their methodological quality and three grades of recommendations were proposed based on criteria from the French Health Authority (Haute Autorité de santé).

1.2.4

General characteristics of the studies

Forty-four publications were identified: 11 articles were case reports or based on small numbers of patients (< 7) and were excluded from the selection. A total of 33 studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were selected. Most of them concerned complete or incomplete traumatic SCI ( n = 29), but other aetiologies were included, such as syringomyelia or benign spinal cord tumor . These studies evaluated the efficacy of antiepiletic drugs used alone or in combination (11 trials), antidepressants (alone or in combination) (7 trials), opioids (4 trials), local anesthetics and oral congeners (intravenous lidocaine, mexiletine) (4 trials), NMDA antagonists (2 trials) and propofol (2 trials). Only 18 randomised double blind controlled studies were conducted: these included 12 which included exclusively SCI patients and six which also concerned other central lesions or peripheral nerve lesions ( Table 1 ). Fifteen studies used a cross over design, four used a parallel group design and only one was multicentric. Only two studies compared the efficacy of treatments between pain at the level of injury and pain below level, three compared incomplete and complete SCI and one compared cervical and dorsal injuries. Eight studies evaluated quality of life, sleep or comorbidities. A few studies included quantitative sensory testing: allodynia to brush (10 studies), sometimes other types of allodynia and hyperalgesia (static or punctate mechanical, heat or cold) (7 studies). Two studies evaluated the predictive value of an IV test (morphine, lidocaine) on the subsequent response to an oral drug.

| Classes | Authors | Active molecule | N total/SCI patients | Daily dosage and duration | Adm. mode | Methodology | Results primary criterion (pain) | Impact on symptoms, QOL, sleep, depression/anxiety and results (+or-) | Level | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | Davidoff et al. (1987) Cardenas et al. (2002) Rintala et al. (2007) | Trazodone Amitriptyline Amitriptyline | 18 84 22 | 150 mg/d, 6 wks 50 mg (10–125), 6 wks 150 mg, 9 wks | Oral Oral Oral | Parallel gr Parallel gr Cross over | Trazodone = Pbo Ami = benztropine Ami > Diphenhydramine | MPQ −, Mood − QOL−, mood −, handicap−, MPQ− CESD-SF − | 2 1 2 | 9 (1.8-inf) NS ND |

| Antiepileptics | Drewes et al. (1994) Finnerup et al. (2002) Tai et al. (2002) Levendoglu et al. (2004) Siddall et al. (2006) Vranket al. (2007) Rintala et al. (2007) | Valproate Lamotrigine Gabapentin Gabapentin Pregabalin Pregabalin Gabapentin | 20 22 7 20 137 40/21 22 | 1800 mg (600–2400), 3 wks 400 mg, 9 wks 1800 mg, 4 wks 2850 (900–3600 mg),8 wks 460 mg (150–600 mg), 12 wks 150–600 mg, 4 wks 3600 mg, 9 wks | Oral Oral Oral Oral Oral Oral Oral | Cross over Cross over Cross over Cross over Parallel gr Parallel gr Cross over | Valproate = Pbo (MPQ) Lamotrigine = Pbo Gabapentin = Pbo(NPS) Gabapentin > Pbo Pregabalin > Pbo Gabapentin = Pbo | – MPQ, allodynia, QOL − Mood + Sleep +, symptoms + QOL, sleep, anxiety + QOL (SF36−, euroqol+) CESD-SF − | 2 1 2 2 1 1 2 | 10 (2.7–inf) NS ND ND 7.1 4 ND |

| Opioids | Eide et al. (1995) Attal et al. (2002) Kupers et al. (1991) Rowbotham et al. (2003) | Alfentanil Morphine Morphine Levorphanol a | 9 15/9 14/8 81/6 | 7 + 12 mg/kg, 20 min 16 mg (9–30), 20 min 0.3 mg/kg in 5 bolus 2.7 and 8.9 mg | IV IV IV Oral | Cross over Cross over Cross over Parallel gr | Alfentanil > Pbo Morphine = Pbo Morphine = Pbo Strong dosage > weak | Allodynia + summation − Allodynia to brush + Affective Score MPQ + Mood − , MPI− | 2 1 2 1 | ND 3 (1.6–40) ND NA |

| Local anesthetics | Attal et al. (2000) Finnerup et al. (2005) Kvrastrom et al. (2005) Chiou-Tan et al. (1996) | Lidocaine Lidocaine Lidocaine Mexiletine | 16/10 24 10 11 | 5 mg/kg, 30 min 5 mg/kg, 30 min 1.5 mg/kg, 40 min 450 mg, 4 wks | IV IV IV Oral | Cross over Cross over Cross over Cross over | Lidocaine > Pbo Lidocaine > Pbo Lidocaine = Pbo Mexiletine = Pbo | Allodynia to brush, pressure+ Dysesthesia to brush + Allodynia to brush − MPQ –Barthel index | 1 1 2 2 | 5 (1.6–inf) 3 (1.6-8.1) NS ND |

| NMDA antagonists | Eide (1996) Kvarstrom et al. (2005) | Ketamine Ketamine | 9 10 | 0.15 mg/kg, 20 min 0.4 mg/kg, 40 min | IV IV | Cross over Cross over | Ketamine > Pbo Ketamine > Pbo | Allodynia to brush + Allodynia to brush + | 2 2 | ND ND |

| GABA agonists | Canavero et al. (1995) Canavero et Bonicalzi (2004) | Propofol Propofol | 32/8 44/21 | 0.2 mg/kg, bolus 0.2 mg/kg, bolus | IV IV | Cross over Cross over | Propofol > Pbo Propofol > Pbo | Allodynia to brush + Allodynia to brush + | 2 2 | ND ND |

1.2.4.1

Antiepileptic drugs

Antiepileptic drugs are major pharmacological classes for the treatment of neuropathic pain .

1.2.4.2

Gabapentin and pregabalin

Gabapentin and pregabalin are the most commonly used antiepileptic drugs for SCI pain: they act on a specific subunit (alpha2delta) of calcium channels, which in turn contributes to reduce central sensitization. Two prospective open studies (level 2) and one retrospective study (level 4) suggested the efficacy of gabapentin on traumatic SCI pain even in the long-term (3 years). This efficacy was confirmed by a randomized controlled study of 20 traumatic SCI patients on pain at or below level and on several other neuropathic symptoms (hot, superficial pain, deep pain, unpleasant characteristics). In this study gabapentin was titrated up to 3600 mg/day (level 2). However two smaller randomized controlled studies were negative: one study (level 2) comparing gabapentin (up to 3600 mg/day) to amitriptyline and to an “active ” placebo (diphenydramine) in 38 SCI patients (22 completers) did not report significant difference between gabapentin and the placebo (level 2); a small study (7 patients) was also negative on the primary outcome with gabapentin titrated to 1800 mg/day (level 3), but these negative data may be in part related to the small sample size. In these studies, the most common adverse effects were somnolence, asthenia, dizziness, gastrointestinal disorders, mouth dryness, headache, weight gain and peripheral edema. However, in one study the side effects were moderate, mainly consisting in somnolence and edema, and did not require to stop the treatment.

The efficacy of pregabalin (with a structure and mechanisms of action similar to gabapentin) titrated from 150 to 600 mg/day (mean dosages 450 mg/day) was recently demonstrated in a large multicenter study of 12 weeks duration including 137 patients with traumatic (complete or incomplete) SCI pain (level 1). An improvement was also reported on anxiety disorders and sleep quality. The impact of pregabalin was similar on pain at or below level, regardless of the level of injury (paraplegia, tetraplegia) and the concomitant treatments (which were used by almost 70% of the patients (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, other antiepileptic drugs, antispastic drugs). However such efficacy was moderate; thus the Number Needed to treat was 3.9 based on pain decrease by at least 30% and 7.1 based on pain decrease by at least 50%. A more recent controlled study (level 1) using a flexible dosage of pregabalin (150 to 600 mg/day) confirmed this efficacy (with a better response rate) in a smaller group of patients (40 patients with central pain including 21 SCI patients), but pregabalin had a poor effect on quality of life . In the first study , pregabalin induced several adverse effects mainly consisting of somnolence (41%) and dizziness. The other less frequent adverse events (20% or less) were edema, weight gain, mouth dryness, constipation, and rarely memory disorders, amblyopia thought disorders, paresthesias, infection and muscle weakness. The rate of dropout from this study because of side effects was 21% for pregabalin and 13% for the placebo. The second study did not report any difference in side effects between pregabalin and placebo, probably because patients were using less concomitant treatments (particularly benzodiazepines).

1.2.4.3

Other antiepileptic drugs

One placebo-controlled study using lamotrigine in traumatic SCI patients (with pain at or below level) was negative on pain and all other efficacy outcomes (quality of life, sleep, allodynia to brush, mechanical and thermal pain thresholds) (level 1). However in a post hoc analysis, lamotrigine was found effective in a subgroup of patients ( n = 7) with incomplete SCI and mechanical allodynia (to brush) at level. Although minor adverse events were similar in the lamotrigine and placebo groups, one lamotrigine treated patients dropped out prematurely because of severe skin rash.

One placebo-controlled study of 20 traumatic SCI patients (with paraplegia or tetraplegia) with pain below level failed to observe significant effects of sodium valproate despite adequate dosages (average 1800 mg daily, ranging from 600 to 2400 mg/day during 3 weeks) (level 2) . The limited required duration of pain at baseline (≥ 1 month) might have accounted for spontaneous improvement in some cases and contributed to enhance the placebo response. One prospective non-randomized study suggested the efficacy of carbamazepine combined to amitriptyline versus electro-acupuncture in SCI patients (level 4) . There is only one retrospective open study reporting the efficacy of clonazepam combined to amitriptyline in SCI pain (level 4). These studies not provide with adequate information regarding the efficacy of these antiepiletic drugs, which were combined to other treatments. None of the other available antiepileptic drugs were assessed in open or controlled studies including a sufficient sample of patients with SCI pain. One unpublished controlled study evaluated the efficacy of topiramate on SCI pain.

1.2.4.4

Antidepressant drugs

Antidepressant drugs are the other commonest drug class used for neuropathic pain. Their analgesic effects is independent from their thymoanaleptic action and is mediated in part by an action on norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, thus contributing to reinforce descending inhibitory controls.

1.2.4.5

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs (TCAs)

Three open studies of poor quality (two prospective – level 3 and one retrospective [level 4] suggested the efficacy of TCAs [mainly amitriptyline]) combined to other treatments (neuroleptics: flupenthixol, carbamazepine, clonazepam and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) on SCI pain . More recently, two double-blind studies compared the efficacy of amitrptyline to an “active” placebo (mimicking the side effects of TCAs) in patients with SCI pain (most often traumatic); the first study including 84 patients (level 1) did not report any improvement with amitriptyline (mean dosage 50 mg/day for 6 weeks) compared to placebo on SCI pain . These negative data, which contrast with most results obtained with amitriptyline in neuropathic pain including central poststroke pain could be due to low dosages of amitriptyline and the poor assessment of neuropathic pain. In fact, the main efficacy outcome of this study was pain in general (including musculoskeletal and visceral pain) and only regression analyses were performed to determine whether the efficacy of the drug was influenced by the presence of neuropathic pain (observed in almost half of the patients) without quantifying it. This level 1 study does not provide with a sufficient level of evidence regarding the efficacy of amitriptyline in neuropathic pain. The second study (level 2) conducted in 38 patients (of whom 22 completed the study, i.e. 58% of the group) used a cross over design versus placebo and gabapentin . This study found a moderate efficacy of high dosage amitriptyline (150 mg/day) compared to gabapentin and placebo, but only in a subgroup of patients with depressive symptoms, suggesting that the analgesic effect of amitriptyline was here strongly related to its antidepressant efficacy. TCAs induced several adverse effects in both studies, consisting mainly of mouth dryness (39% and 64%, respectively), constipation (32% and 11%, respectively), but also aggravation of spasticity (25% and 11%, respectively) and of dysyria (11% and 5%, respectively), which can be a genuine concern in the context of SCI. Furthermore, in the first study only 29% of patients continued their treatment after 4 months.

1.2.4.6

Other antidepressant drugs

To date, evidence for the efficacy of non-TCAs is lacking in SCI pain. Thus a small single blind study (the patients were not informed of the objectives of the study) did not find any efficacy of reboxetine, a noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (unavailable in France) in six patients with central pain including three SCI patients (level 3). A double blind placebo-controlled study was also negative with trazodone (a serotonin antidepressant drug which is not available in France) on burning pain and paresthesia associated with traumatic SCI (level 2). This study suggests the ineffectiveness of serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) in SCI pain, which is in line with other results in other neuropathic pain conditions . There is no published study of the efficacy of SNRIs (venlafaxine, duloxetine) on central pain.

1.2.4.7

Opioids

There are no placebo-controlled studies of the efficacy of opioids (using repeated dosages) or tramadol in SCI pain. However one level 1 controlled study comparing the efficacy of low doses (2.7 mg/day) versus high doses (8.9 mg/day) of levorphanol (a mu and kappa opioid agonist which is unavailable in France) in 81 patients with multi-aetiology neuropathic pains including six patients with incomplete SCI reported a higher analgesic efficacy of high dosages compared to low dosages in most of the aetiologies considered (SCI, postherpetic neuralgia, multiple sclerosis, painful neuropathies) . Adverse effects observed in the high dosage group included personality disorders (irritation, mood, anxiety), fatigue, confusion and dizziness. Three double blind placebo-controlled studies evaluated the efficacy of several IV opioids (morphine, alfentanil) on SCI pain or various types of neuropathic pains including SCI patients (level 1 and 2, respectively). These studies reported discrepant results on spontaneous pain intensity, with one positive and two negative studies; one of these trials only reported an effect on the affective dimension of pain . However a subgroup of patients (46%) responded to morphine in one study . Brush-induced allodynia was alleviated by opioids in these studies, whereas other evoked pain symptoms (hyperalgesia to pressure, allodynia and hyperalgesia to heat or cold, temporal summation) were not affected. Adverse effects mainly included somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, visual or hearing perception disorders, malaise. One study assessed the predictive value of IV morphine on the subsequent response to oral morphine and found that the non-responsive patients to the IV test were not responders to subsequent oral morphine whereas half of those who responded to the IV test continued their treatment after 1 year.

1.2.4.8

Local anaesthetics and oral congeners

Lidocaine is a use-dependent sodium channel blocker which may have analgesic effects in central pain. Three placebo-controlled studies assessed the efficacy of IV lidocaine on neuropathic SCI pain (level 1 and 2). Two of the three studies using high doses of IV lidocaine (5 mg/kg IV) including a total of 32 patients with traumatic SCI ( n = 25) or syringomyelia ( n = 7) were positive on spontaneous pain (at or below level) whereas one study using a much lower dose (1.5 mg/kg IV) was negative. The two positive studies also reported the efficacy of IV lidocaine on allodynia or dysesthesia to brush, hyperalgesia to punctate mechanical stimuli whereas IV lidocaine seemed less effective on allodynia and hyperalgesia to cold and temporal summation. In these studies, the adverse effects mainly included dizziness, somnolence, light-headedness, dry mouth, dysarthria, nausea, perioral paresthesias. However, although no severe complications were reported in these studies, IV lidocaine used at high dosages may lead to cardiovascular and neurological (seizures) complications. IV lidocaine is difficult to use in clinical practice: thus in the study of Attal et al. , only two patients out of 16 reported a long-term effect of IV lidocaine; this study did not find predictive value of IV lidocaine on the efficacy of oral mexiletine, a synthetic analog (none of the patients continued mexiletine on the long-term because of a poor benefit/tolerability ratio). The predictive value of the efficacy of IV lidocaine on other sodium channel blockers (antiepileptic drugs) has not been demonstrated.

1.2.4.9

Mexiletine

One randomized placebo-controlled study was negative with mexiletine (450 mg/day) in 11 SCI patients (level 2). However, the small number of patients and low dosages of mexiletine limit the conclusions of this study.

1.2.4.10

NMDA receptor antagonists

Two double-blind controlled studies evaluated the efficacy of IV ketamine, a potent NMDA antagonist, in SCI patients (level 2). These two studies reported a significant improvement of spontaneous pain, brush evoked allodynia and temporal summation (pain induced by repeated stimulation). However ketamine induced several adverse effects: dizziness, perception disorders, mood disorders, feeling of unreality, nausea and fatigue. These studies did not evaluate the potential long lasting effects of ketamine nor did they assess the predictive value of ketamine on the subsequent efficacy of oral NMDA antagonists.

1.2.4.11

GABAergic agonists

Two controlled studies from the same group reported the efficacy of IV propol (Diprivan ® ), a GABAergic agonist on central pain (spontaneous pain, brush induced allodynia) including SCI patients (level 2). These results suggested the implication of GABAergic inhibition in the mechanisms of central pain. However, there are no studies of the efficacy of oral baclofen in SCI pain.

1.2.4.12

Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids (Sativex ® , tetrahydrocannabinol) have not been specifically studied in SCI pain. However their efficacy has been demonstrated in two double blind placebo-controlled studies in central pain related to multiple sclerosis, which presents with numerous similarities with SCI pain .

1.2.4.13

Other pharmacological treatments

There is no study of the efficacy of other pharmacological classes (level 1 or II analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, tramadol, oral clonidine) in SCI pain. However, it may be pointed out that tramadol has been found effective in peripheral neuropathic pain .

1.3

Discussion and recommendations

1.3.1

Evidence for efficacy and quality of the studies

Pregabalin is the only pharmacological treatment that has been specifically assessed in SCI pain ( Table 2 ) on the basis of placebo-controlled studies (grade A recommendation). Discrepant results have been obtained with gabapentin in this specific indication on the basis of two level 2 studies. Amitriptyline has been found effective at high dosages in SCI patients with depressive symptoms only in one level 2 study (presumed efficacy in this subgroup, level B), but ineffective on SCI pain (including several types of pain) in one level 1 study. Opioids at repeated dosages have not been evaluated specifically in SCI pain in placebo-controlled studies but a level 1 comparative study in multi-aetiology neuropathic pain including SCI pain has reported a better response rate for high doses of an opioid agonist compared to low doses (grade B in SCI patients).

| Pharmacological treatments | Level of scientific evidence | Grade of recommendation for SCI pain |

|---|---|---|

| Antiepileptic drugs | ||

| Gabapentin | 2 | B (discrepant results) a |

| Pregabalin | 1 | A (scientific evidence for efficacy) |

| Lamotrigine | 2 | B (presumed inefficacy b ) |

| Valproate | 2 | B (presumed inefficacy) |

| Clonazepam | 4 | C (low level of evidence) |

| Carbamazepine | 3 | C (low level of evidence) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant drugs | ||

| Amitriptyline | 2 | B (presumed efficacy in a subgroup of depressed patients) |

| Opioids | ||

| Levorphanol c | 2 | B (presumed efficacy) |

| IV Morphine | 2 | B (presumed inefficacy d ) |

| IV Alfentanil | 2 | B (presumed efficacy) |

| Local anesthetic drugs/equivalent | ||

| IV lidocaine | 2 | B (presumed inefficacy) |

| Mexiletine | 2 | B (presumed efficacy) |

| GABAergic agonists | ||

| IV Propofol | 2 | B (presumed efficacy) |

a One positive study (20 patients) and one negative study (22 patients).

b Efficacy on the basis of one study on a small sub-group of patients with incomplete SCI and allodynia.

c Treatment not available in France.

Valproate, mexiletine and lamotrigine have been assessed in level 1 and 2 controlled studies. These trials were negative (presumed inefficacy, grade B), but one study found efficacy of lamotrigine in a subgroup of patients with incomplete SCI and allodynia (presumed efficacy in this subgroup). Finally the level of evidence is insufficient for clonazepam and carbamazepine (grade C).

Regarding IV treatments, discrepant results have been reported for opioids (morphine, alfentanil) in SCI pain (inefficacy on spontaneous pain but effects on allodynia to brush). However, one study reported that IV morphine was predictive of the subsequent response to oral opioids (Grade B). Small controlled studies reported positive effects of IV lidocaine, IV ketamine and propofol (grade B).

1.3.2

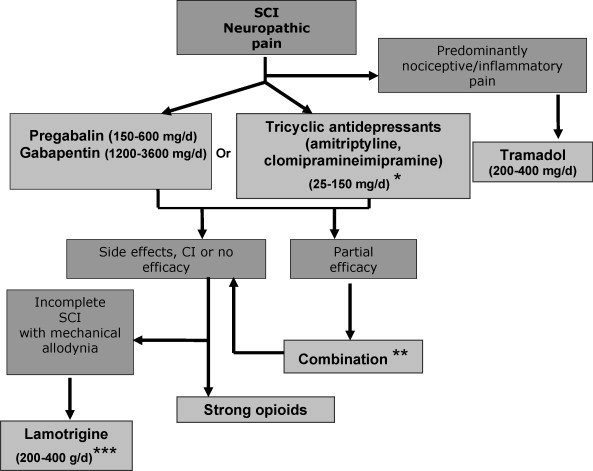

Therapeutic algorithm

We propose a therapeutic algorithm for SCI neuropathic pain management ( Fig. 1 ). This algorithm takes into account the evidence for efficacy in pain, neuropathic symptoms and impact on quality of life and sleep, as well as the side effect profile of treatments. It also takes into account level information regarding the drug prescription in France, potential difficulties of use (e.g., IV ketamine) and stock management (e.g. cannabinoids). Given the limited number of double blind studies in SCI pain, the evidence for efficacy in other peripheral or central neuropathic pain conditions has also been considered. In fact, centrally acting drugs may have a similar efficacy in peripheral or central pain . This algorithm is also based on expert opinion in the lack of available data for some treatments.

1.3.2.1

First and second line therapy

Pregabalin (150 to 600 mg/day BID) (scientific evidence, grade A), and gabapentin (1200–3600 mg/day TID) (lower level of evidence for SCI pain- grade B- but confirmed efficacy in peripheral neuropathic pain, grade A) can be considered as first line treatments for central pain due to SCI. These treatments are safe and effective on pain and impact on sleep, anxiety and to some extent quality of life. However their efficacy is moderate and their side effects may be a concern for SCI patients (e.g., edema, weight gain). There are no studies comparing pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain. However, pregabalin is easier to use and has a better bioavailability. Furthermore, its efficacy is dose-dependant, which is also an advantage. Finally contrary to gabapentin, pregabalin has received approval for the treatment of central pain in France.

TCAs can also be proposed first line on the basis of their efficacy in other neuropathic pain conditions (see also the French recommendations for neuropathic pain treatment), particularly in patients with pain and depressive symptoms (grade B, presumed efficacy in this subgroup). TCAs include amitriptyline (only drug studied in SCI pain), imipramine or clomipramine (10–250 mg/day, median dosage 75 mg/day) which all have official approval for use in neuropathic pain in France. However, TCAs are difficult to use in patients with spasticity, due to a risk of aggravation, and in those with dysyria and constipation. Furthermore they can interfere with peripheral anticholinergic treatments (e.g., Ditropan ® ), which are often used by SCI patients.

In patients with a predominant non neuropathic component associated with neuropathic pain, tramadol (200–400 mg BID for the sustained release drugs) can be proposed alone or in combination with antiepileptic drugs (professional consensus). The analgesic effect of tramadol has not been specifically studied in SCI pain, but several studies have demonstrated its efficacy in peripheral neuropathic pain conditions and in chronic musculoskeletal and inflammatory pain. Care should be taken when combining tramadol with antidepressants particularly those acting on serotonin reuptake inhibition, such as SSRIs and some TCAs, due to an increased risk of serotonin syndrome.

1.3.2.2

Other treatment options

When first line treatments fail, strong opioids (grade B in SCI; shown effective on other neuropathic pain conditions) can be proposed. These include sustained release morphine agonists and oxycodone, but oxycodone is only approved for use in cancer pain in France. Dosages are variable from one patient to another and are based on individual titration. Opioids are difficult to use in some SCI patients, due to increased risk of dysuria and constipation, and their long-term use should be carefully monitored due to potential risks of dependancy . Lamotrigine may also be proposed second/third line specifically in incomplete SCI patients with mechanical allodynia (grade B) and on the basis of another positive placebo-controlled study in central post-stroke pain (grade B). This treatment does not have official approval for use in analgesia in France and may induce potentially severe skin rash (toxic epidermolysis, Lyell syndrome). For this reason, the drug must be titrated slowly (25 mg/day during the first week, then increase by 25 mg to 50 mg every 2 weeks).

1.3.2.3

Refractory SCI pain

In refractory cases cannabinoids can be proposed (dronabinol or tetrahydrocannabinol is available in France through a temporary authorization procedure for use) based on positive results in other types of central pain (multiple sclerosis). IV lidocaine (5 mg/kg for 30–45 min) and IV ketamine (0/15 mg/kg for 20–40 min) may be used in specialized centers (no official approval for use in analgesia). However, these treatments are not recommended in routine clinical practice, their analgesic effects are generally transient and their predictive nature for the effects of oral analogs has not been confirrmed. Despite positive studies from the same group, IV propofol is only currently used for anaesthetic procedures in France and cannot be recommended for chronic SCI pain.

1.3.2.4

Combination therapy

There is no need to prescribe combination therapy as first line in SCI pain in the lack of evidence for synergistic or additional effects compared to monotherapy, particularly due to the enhanced risk of cumulative adverse events. However combining two different drug classes can be proposed in case of a partial response to first or second line therapy. Interestingly gabapentin combined to morphine has recently been found more effective than monotherapy with each drug alone in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain, which suggests the relevance of such combination .

Appendix 1 shows the responses of a panel of physicians regarding their therapeutic practice in SCI pain, which can thus be compared to expert recommendations.

One hundred and fifty six physicians answered the survey, including 116 physicians who attended the experts conference on pain management and 50 which responded via the SOFMER website. A large majority of physicians (85.8%) prescribe a pharmacological treatment as first line therapy. For 58.6% of them, this prescription is based on drugs acting on peripheral neuropathic pain. The use of strong opioids is very rare: 71.4% of physicians rarely prescribe them and 20.1% never prescribe them. About 22.6% of them fequently propose a combination therapy as first line. In light of the evidence-based recommendations, the physicians’ routine clinical management of SCI pain thus appears encouraging. However for most of them, the prescription choice is based on peripheral neuropathic pain. The questionnaires did not specify the names of the prescribed drugs. We encourage to guide the therapeutic decisions on the basis of expert recommendations regarding the drugs available for pain management.

1.4

General conclusions

In contrast to other types of neuropathic pains, few controlled studies have been conducted in SCI neuropathic pain. These studies have generally included small samples of patients and the level of evidence for the efficacy of most treatments is moderate or insufficient. Furthermore, no study has directly compared several drug classes in SCI pain. Direct comparative studies and trials including large cohorts of SCI patients are strongly encouraged in the future.

1.5

Conflicts of interests

Pfizer, Lilly and Grunenthal societies paid honorarium to Dr Attal these last two years for clinical studies or consultations as an expert.

Appendix 1

Results from the questions asked to the 116 physicians who attended the experts conference on pain management at the SOFMER and the 50 other physicians who answered via the SOFMER website

For chronic neuropathic pain management in SCI patients when prescribing a pharmacological treatment (oral, transdermal or IV mode of administration).

- 1.

Do you treat this pain just like peripheral neuropathic pain?

dnk: 1.8%

Yes: 58.6%

No (I use a specific therapeutic strategy): 39.6%

- 2.

Do you use pharmacological treatments?

dnk: 3.6%

As first-line therapy: 85.8%

After other medical treatments failed (rehabilitation, stimulation…): 10.6%

- 3.

Do you prescribe strong opioids (morphine) for this type of pain?

dnk: 1.8%

Often: 6.7%

Rarely: 71.4%

Never: 20.1%

- 4.

Do you prescribe an association of different drugs?

dnk: 1.8%

Often (first-line therapy): 22.6%

Sometimes (second-line therapy): 73.7%

Never: 1.9%

dnk: does not know

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Le traitement des douleurs neuropathiques d’origine médullaire reste extrêmement difficile, en dépit de l’arrivée de nouvelles molécules sur le marché. Cette difficulté est accrue par le fait que les douleurs neuropathiques des blessés médullaires s’inscrivent généralement dans un contexte de douleurs et de pathologies multiples, contribuant à majorer leur handicap et à réduire la tolérance des traitements pharmacologiques. Ces derniers sont donc rarement utiles seuls, et doivent nécessairement s’intégrer dans une prise en charge plus globale, associant généralement de la rééducation et parfois de la psychothérapie. À ce jour, malgré un nombre croissant d’essais cliniques réalisés dans le domaine des douleurs neuropathiques en général, peu d’essais cliniques randomisés contrôlés ont été spécifiquement consacrés aux douleurs neuropathiques d’origine médullaire et la mise en œuvre d’un traitement pharmacologique pour ces douleurs se fonde généralement sur les résultats obtenus dans les douleurs neuropathiques périphériques . Les objectifs de ce travail sont de présenter les preuves d’efficacité et de tolérance des traitements pharmacologiques des douleurs neuropathiques associées aux lésions médullaires, utilisés à doses uniques ou répétées, et de proposer des recommandations thérapeutiques sur l’utilisation de ces traitements dans ces douleurs.

2.2

Matériel et méthode

2.2.1

Stratégie de recherche

La recherche bibliographique a été effectuée systématiquement sur les bases de données Medline (1966–2007), Embase (1995–2007) ou Cochrane (1995–2007). Les mots clés étaient les suivants : spinal cord injury(ies) pain ou central pain associé à : pharmacological treatment ou randomized controlled trial ou à des traitements/classes pharmacologiques spécifiques ( analgesics, NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, amitriptyline, antiepileptics, gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, clonazepam, lamotrigine, valproate, phenytoin, topiramate, opioids, morphine, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol, cannabinoids, tetrahydrocannabinol, baclofène , clonidine ). Les articles pertinents étaient aussi identifiés à partir de citations de journaux référencés (notamment méta-analyses ou études systématiques) ou de chapitres de livres .

2.2.2

Critères de sélection

Les critères de sélection des études étaient les suivants :

- •

toutes études thérapeutiques de niveaux 1 à 4, selon la classification de l’Anaes ou méta-analyses de ces études ;

- •

les études dont l’objectif principal est de décrire l’efficacité d’un traitement sur les douleurs neuropathiques centrales, lésionnelles ou sous-lésionnelles, des lésions médullaires, isolées ou associées à d’autres types de syndromes douloureux. Les études évaluant plusieurs étiologies étaient inclues à condition de fournir des données d’efficacité spécifique sur les douleurs des lésions médullaires ou d’inclure une proportion importante de ces douleurs ;

- •

les articles en français ou en anglais ;

- •

les publications dans des revues à comité de lecture ;

- •

les traitements administrés par voie générale (orale, transdermique ou intraveineuse).

Les critères de non-inclusion étaient les suivants :

- •

les traitements par voie locale ou locorégionale ;

- •

les publications ne permettant pas de décrire une efficacité sur la douleur (par exemple, données épidémiologiques) ;

- •

la douleur non neuropathique (par exemple : douleur de spasticité, douleur viscérale, douleur musculosquelettique) ou douleur neuropathique périphérique (par exemple : douleur radiculaire lésionnelle, douleur neuropathique sus-lésionnelle) ;

- •

les chapitres de livres et abstracts ;

- •

les cas cliniques comportant moins de sept patients ou études contrôlées de cas isolés.

2.2.3

Analyse et présentation des données

Pour chaque étude, les informations concernant la méthodologie, les critères d’inclusion et d’exclusion, le nombre de patients inclus, les doses utilisées et la voie d’administration, les méthodes de randomisation et de maintien de l’aveugle, la description des sorties d’études, les résultats obtenus sur les critères d’efficacité primaire et secondaire et les données de tolérance ont été analysées. Les données d’efficacité ont été analysées sur la douleur neuropathique lésionnelle ou sous-lésionnelle en général, mais aussi, lorsque la donnée était disponible, sur les différents symptômes douloureux (douleur continue, paroxystique, allodynie, hyperalgésie), sur le handicap, la qualité de vie et les comorbidités psychiatriques (troubles anxieux et dépressifs). La proportion de répondeurs, estimée à partir des nombre nécessaire à traiter (NNT) a été mentionnée pour toutes les études permettant ce calcul. Le NNT est défini par le nombre de patients qu’il est nécessaire de traiter pour avoir un répondeur au produit actif. La réponse thérapeutique se fonde généralement sur une réduction de la douleur d’au moins 50 % ou à défaut, sur le nombre de patients présentant un soulagement bon ou très bon. Les études ont été classées en quatre niveaux selon leur qualité méthodologique et les recommandations en trois grades (A, B et C), selon les recommandations de l’Anaes.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Caractéristiques générales des études

Un total de 44 publications a été identifié : 11 articles étaient des cas cliniques isolés ou portant sur un faible nombre de patients (< 7) et ont été exclus de la sélection. Au total, 33 études satisfaisant aux critères d’inclusion ont été retenues. La grande majorité des études ont porté sur des lésions médullaires traumatiques, complètes ou incomplètes ( n = 29), mais certaines ont aussi inclus d’autres étiologies, telles que syringomyélie ou tumeur bénigne médullaire . Ces études ont évalué l’efficacité des antiépileptiques seuls ou en association , des antidépresseurs seuls ou associés , des opiacés , des anesthésiques locaux et apparentés (lidocaïne i.v., méxilétine) , des antagonistes des récepteurs NMDA et du propofol . Seuls 18 essais contrôlés randomisés en double insu ont été réalisés, dont 12 ont porté spécifiquement sur des lésions médullaires et six ont aussi inclus d’autres lésions centrales ou des lésions nerveuses périphériques ( Tableau 1 ). Ces essais ont utilisé une méthodologie en cross over , rarement en groupes parallèles et un seul est multicentrique. Très peu d’études contrôlées ont comparé l’efficacité des traitements entre douleurs lésionnelles et sous-lésionnelles , entre lésions complètes ou incomplètes , et entre lésions de niveau cervical ou dorsal . Huit ont évalué la qualité de vie, le sommeil ou les comorbidités psychiatriques. Quelques études ont comporté une évaluation quantifiée des symptômes douloureux, permettant ainsi d’analyser l’efficacité des traitements sur l’allodynie au frottement , et parfois d’autres sous-types d’allodynie et d’hyperalgésie (mécanique à la pression, au froid, au chaud) . Deux études ont évalué l’intérêt prédictif d’un test thérapeutique intraveineux (morphine, lidocaïne) sur la réponse ultérieure à un traitement par voie orale.