Fig. 7.1

Outerbridge I chondropathy of the internal femoral condyle (a), internal tibial plateau (b), trochlear groove (c) and of the patella (d)

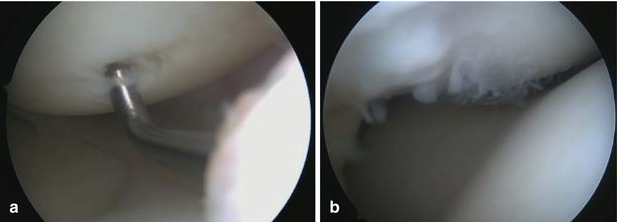

Fig. 7.2

Outerbridge II chondropathy of the internal femoral condyle (a) and trochlear groove (b)

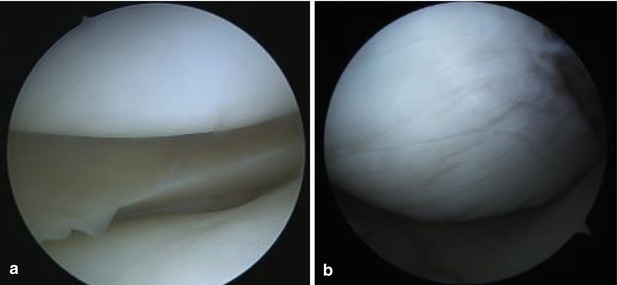

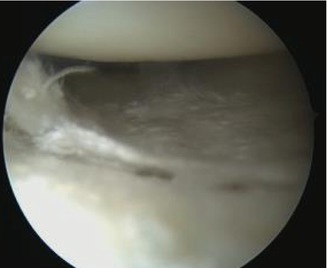

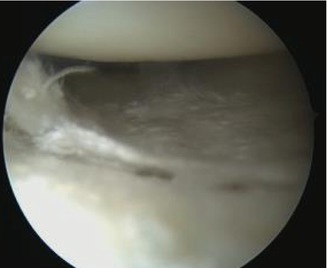

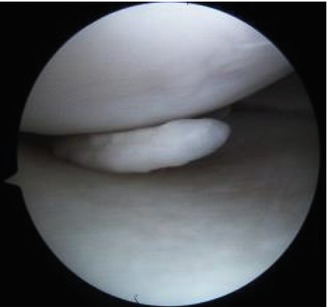

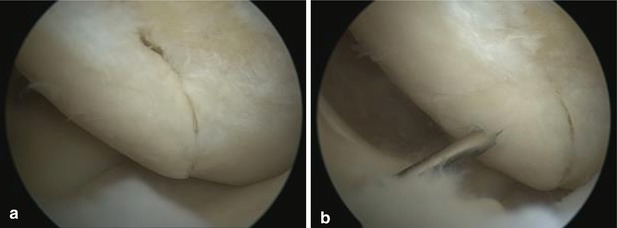

Fig. 7.3

Internal compartment with intact cartilage on the femoral and tibial condyles (a). Outerbridge II lesion of the internal femoral condyle. This is a lesion typical to chronic ACL deficient knees (b)

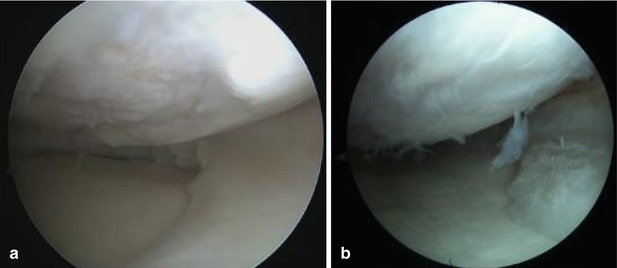

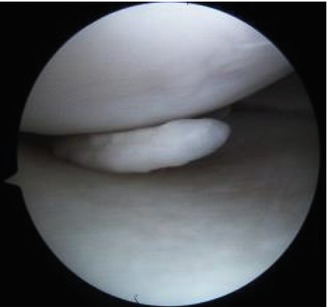

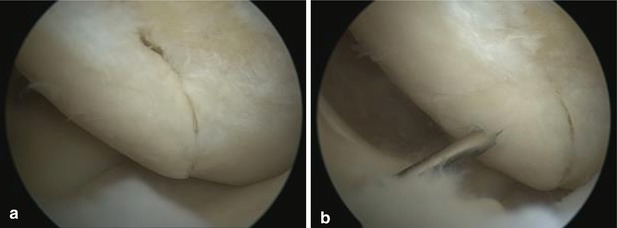

Fig. 7.4

Outerbridge III lesions of the internal femoral condyle. Note the meniscus has been partially removed, this goes to show that these are chronic lesions (a, b)

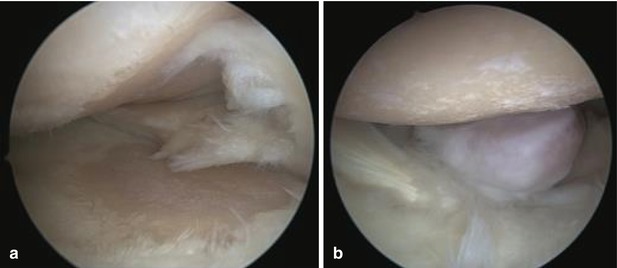

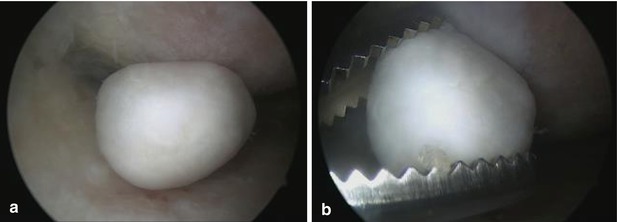

Fig. 7.5

Outerbridge IV lesions. Left image (a) shows mirrored lesions and in right image (b) we can see an articular loose body in the lateral recess

7.1 The Noyes Classification

Grade 1: Cartilage surface intact

1A = some remaining resilience;

1B = deformation

Grade 2A: Cartilage surface damaged (cracks, fibrillation, fissuring, or fragmentation); with less than half of cartilage thickness involved

Grade 2B: Depth of involvement greater than half of cartilage thickness but without exposed bone

Grade 3: Bone exposed

3A = surface intact;

3B = surface cavitation

The more recent ICRS (International Cartilage Repair Society) classification:

Grade 0: Normal

Grade 1: Nearly Normal (soft indentation and/or superficial fissures and cracks)

Grade 2: Abnormal (lesions extending down to <50 % of cartilage depth)

Grade 3: Severely Abnormal (cartilage defects >50 % of cartilage depth)

Grade 4: Severely abnormal (through the subchondral bone)

The cartilage is an avascular and aneural tissue, thus its regenerative capacities are rather limited and this causes the progressive aspect of these degenerative lesions and the difficulty in treating these lesions. The classic therapeutic options of chondroplasty and microfractures can do only a little to resolve the actual pathology and do so only partially, the result being a fibrocartilage with mechanical proprieties that are not similar to that of the damaged hyaline cartilage and do not actually stop the overall degenerative process.

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition (CPPD) or chondrocalcinosis (Fig. 7.6) is a rheumatologic condition caused by the accumulation of crystals of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate in the connective tissues. It is sometimes used as a synonym for chondrocalcinosis, but the two pathologies, while similar, are not equal. Chondrocalcinosis represents the visible presence of calcification within tissues on an imaging study. According to Richette et al the correct definition would be: ‘chondrocalcinosis’ (CC)—radiographic calcification of articular fibro- or hyaline cartilage; ‘pyrophosphate arthropathy’—structural abnormality of cartilage and bone associated with articular CPPD deposition; and ‘pseudogout’—the clinical syndrome of acute synovitis associated with intraarticular CPPD deposition [2–4].

Fig. 7.6

Crystals of calcium deposited on the medial tibial plateau

Cartilage lesions can also appear secondary to other joint pathologies such as ACL ruptures that cause secondary instability, synovial plicae, especially the mediopatellar plica causes cartilage damage, chronic synovitis or chronic, neglected meniscal tears. Another type of cartilage lesions are the ones caused by the operating surgeon – the iatrogenic injuries. Lack of experience, large instruments and vile maneuvers during joint exploration can cause cartilage lesions so an absolute delicacy is required to perform knee arthroscopic surgery. Another type of iatrogenic injures are those created by drills during the anatomic trans AM placement of the femoral tunnel during ACL reconstructions. To address this special, thinner, drills have been designed with only the diameter of the cutting surface (tip) of the drill changing, while the stem remains the same diameter (Fig. 7.7).

Fig. 7.7

This image shows a iatrogenic cartilage lesion of the trochlear groove made by the aggressive insertion of the canula or another instrument in the suprapatellar compartment of the knee joint

7.2 Articular Loose Bodies

A loose body is a free-floating piece of bone, cartilage or a foreign object in the knee joint, the most common joint for loose bodies. We will present in this chapter two types of articular loose bodies, the chondral and osteochondral types, different, iatrogenic, loose bodies will be presented in the complications chapter (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 7.8

This loose body in the lateral recess of the knee has started to have rounded edges, showing that some time has passed since the lesion was produced

Cartilaginous and bony intra-articular bodies float freely within the synovial fluid and can grow in dimension over time due to the nutritive proprieties of the synovial fluid. The most frequent cause of articular loose bodies is synovial osteochondromatosis, a cartilaginous metaplasia of the synovial membrane. It can also be caused by a fracture with avulsed fragment or detached, calcified meniscus, a detached bone spur, osteochondritis dissecans. Other, less frequent causes are synovial chondrosarcoma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, osteomyelitis and synovial chondrosarcoma.

Loose bodies can be found in knee joints years after the original traumatic event, moving from the suprapatellar compartment to the anterior, internal or external compartments and can cause reversible joint locking. Most often they tend to move in the lateral or medial recess and reside in the suprapatellar or, most often, in the posterior compartment of the knee because of the gravity effect, where they can become incarcerated. Because of the friction forces and the nutritional proprieties of the synovial fluid as the time passes they become rounded or oval in shape, as a more efficient way for them to travel trough the joint space with a minimal risk of creating secondary lesions.

Nevertheless in most of the cases they do create secondary lesions (Fig. 7.9), supplementary cartilage damage and meniscal injuries to name just a few. Chronic synovitis and secondary osteoarthritis both as a result of cartilage damage and synovial inflammation are a common end point, loose bodies are often found during TKA surgery.

Fig. 7.9

Chronic chondral loose body in the internal compartment of the knee

Preoperative diagnosis of loose bodies can prove difficult at times, depending on the imaging method used for this. X-rays can detect osteochondral or calcified articular bodies, but fails to provide data for radiotransparent objects. CT and CT arthrography, while superior to plain X-rays do not provide the same amount of information as MRI does. But the imaging method of choice remains MR arthrography, superior to conventional MR in mapping out articular structures in joints with minimal fluid. No joint infiltration or fluoroscopic guidance is required. Removing articular loose bodies from the knee joint can be technically difficult (Fig. 7.10), especially for those trapped in the posterior compartment, where access is laborious with regular arthroscopic instruments.

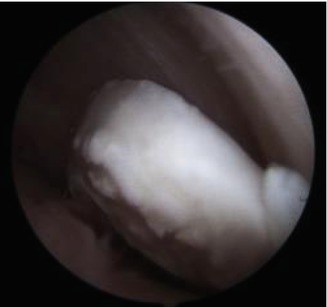

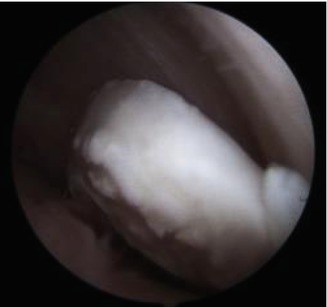

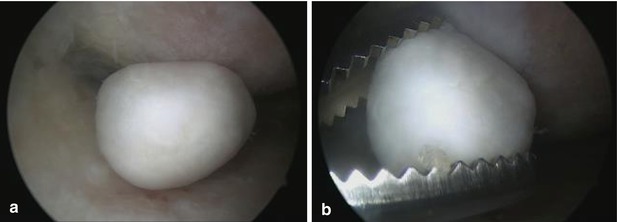

Fig. 7.10

Loose body associated with Outerbridge IV chondropathy (a) and the removal of the loose body (b)

7.3 Osteochondritis Dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans (abbreviated OCD and OD) is a condition in which a fragment of bone in a joint is deprived of blood and separates from the rest of the bone, causing soreness and making the joint give way. While OCD may affect any joint, the most affected joint in the human body is the knee. Left untreated, it leads to secondary osteoarthritis caused by joint incongruity and aberrant wear patterns, especially in adult patients. OCD is classified as a juvenile (JOCD) or adult (AOCD) form based on the skeletal maturity of the patients, i.e. the presence or absence of open growth plates. OCD is one of the most common causes of knee pain in teenagers, with a peak in occurrence in the 10–15 years age group. JOCD has been recognised as a pathological entity for more than 100 years, but its pathogenesis is still widely debated, with no certain cause having been pinned down, it is believed to be caused by repetitive trauma [5–7] (Fig. 7.11).

Fig. 7.11

The chronic cartilaginous lesion is seen with clear delimitation from the normal cartilage (a, b)

Young people are involved in a wide array of sports that require intensive family support, thus early recognition of osteochondral lesions of the knee is easier to make [6, 8]. Osteochondritis dissecans OCD of the knee can be classified in an adult form and a juvenile form. However, these two forms of OCD have a different natural evolution in terms of the disease and the outcomes that they produce. JOCD has a better outcome under conservative treatment than the adult form with high degree of family involvement and commitment, the “compliance triad” of physician, parent, and child being the key element when a conservative treatment plan for JOCD is initiated. JOCD can be further subdivided in a adolescent form a juvenile form, depending on the status of the growth physis [5, 9, 10].

Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans: wide open physis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree