Cheilectomy with and without Proximal Phalangeal (Moberg) Osteotomy

Harold B. Kitaoka

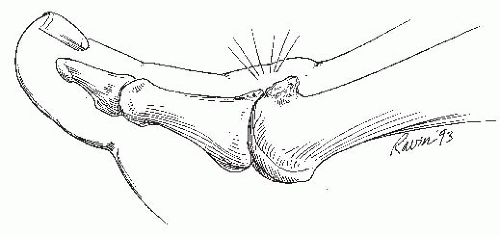

Hallux rigidus is a painful degenerative joint disease affecting the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint and is associated with osteophyte formation and limitation of motion, especially in dorsiflexion. It was first described by Davies-Colley in 1887, and J. M. Cotterill later coined the term hallux rigidus (1). After hallux valgus, it is the most common painful affliction of the great toe, occurring in approximately 2% of the population between the ages of 30 and 60 years. As the degenerative process progresses, proliferation of bone on the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal head increases the size of the joint and blocks dorsiflexion of the proximal phalanx (Fig. 4.1). These changes are possibly initiated by previous occult trauma (1,2). Patients usually present with unilateral symptoms, but it is common for stiffness and the degenerative process to affect the opposite foot. Abnormal gait is common (3), and patients may walk on the lateral border of the foot to minimize painful hallux MTP dorsiflexion.

Nonoperative treatment of the hallux rigidus includes activity modification, administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, footwear alteration, and intraarticular injection of corticosteroids. Shoe modification includes wide and deep toe box to reduce skin abrasion from dorsal osteophytes and irritation of the dorsal-medial cutaneous nerve. A stiff-soled shoe with rocker-bottom, steel, fiberglass shank built in the sole, or rigid carbon fiber orthotic with Morton’s extension, can also help by minimizing the first MTP motion at toe-off.

When nonoperative treatment fails, surgical intervention with cheilectomy should be considered, for mild and selected cases of moderate hallux rigidus (4). It improves pain related to the arthritic joint (Fig. 4.1) or from skin ulceration or abrasion overlying large dorsal osteophytes. The goal of surgery is to excise the proliferative bone on the “lip” of the joint, thereby allowing dorsiflexion motion. Cheilectomy offers the advantage of preserving the length, stability, and flexion-extension strength of the great toe that are often affected with other procedures. An arthroplasty or arthrodesis can always follow a failed cheilectomy, but not vice versa. Other options have been described such as resection arthroplasty, interposition arthroplasty, implant arthroplasty, MTP arthrodesis, and osteotomies about the first MTP joint (5,6). These osteotomies include closing wedge proximal phalangeal osteotomy, proximal metatarsal osteotomy, and distal metatarsal osteotomy (7,6).

Closing wedge osteotomy of the proximal phalanx for hallux rigidus was first proposed by Bonney and Macnab (8) in 1952, and short-term results were reported by Kessel and Bonney (9) in 1958. Closing wedge proximal phalanx osteotomy is, however, best known as the Moberg osteotomy since he popularized this technique (10). The aim of the operation is to move the limited arc of motion at the affected joint to a more dorsiflexed position so that the function is improved. It is applicable in patients with mild to moderate degenerative disease of the first MTP joint due to hallux rigidus. We advocate this procedure for patients with grade II hallux rigidus and reserve the isolated cheilectomy for grade I disease with prominent symptomatic dorsal osteophytes.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

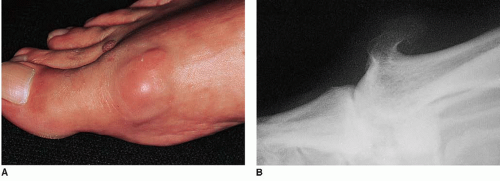

The indications for cheilectomy are hallux rigidus, which is painful, disabling, and refractory to nonoperative treatment. Additional indications include stiff, painful range of motion of the MTP joint, difficulty with footwear, and recurrent bursitis or skin callosity over prominent osteophytes (Fig. 4.2). It may be indicated for recurrent abrasion or skin ulceration over the prominent osteophytes once the ulcer is healed. The contraindications are a foot with vascular insufficiency, infection or ulceration, and sensory neuropathy. A relative contraindication is a patient who is noncompliant.

Cheilectomy with phalangeal osteotomy could be considered in a relatively young, active patient and/or athlete with pain and impairment due to moderate hallux rigidus with marked restriction of dorsiflexion and adequate plantarflexion.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

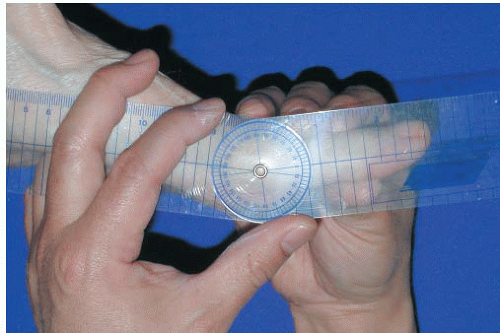

Painful motion and crepitus may occur with sagittal motion. The range of motion of the first MTP should be measured with goniometer and recorded. We use the plantar surface of the foot and the axis of the proximal phalanx for range of motion measurements (Fig. 4.3). Others measure the position of the toe relative to the metatarsal axis, recognizing that the angular measurement obtained is influenced by the height of the arch. During clinical evaluation, care should be taken to note the posture and the range of motion of the interphalangeal (IP) joint. This joint often develops compensatory hypermobility in dorsiflexion. Failure to recognize hyperextension of the IP joint can result in poor outcome and patient dissatisfaction if this joint becomes painful and arthritic postoperatively. The IP joint should be held in a neutral position when measuring MTP motion (see Fig. 4.3), or the degree of the dorsiflexion will be overestimated.

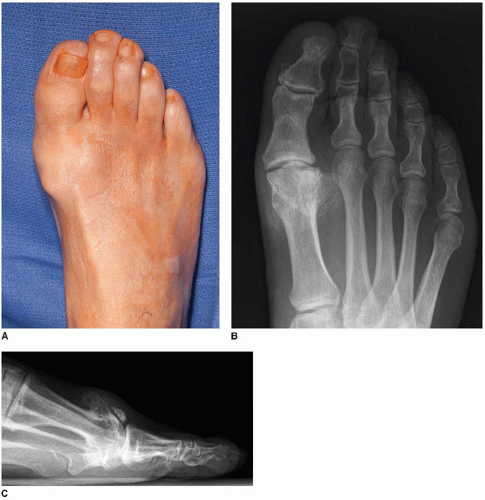

Radiographs should be obtained to evaluate the severity of the joint degenerative disease and to determine the presence of concurrent pathology (11). Radiograph evaluation should include standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views (Fig. 4.4). The AP view can be useful in evaluating medial and lateral osteophytes, toe alignment, joint space narrowing, and condition of the adjacent joints.

FIGURE 4.3 A patient with painful hallux rigidus has restriction of dorsiflexion as measured with a goniometer. |

The standing lateral view is helpful because it demonstrates the dorsal osteophytes and reveals the extent of joint space narrowing. Hyperextension of the IP joint can be appreciated in this view, but this usually is determined clinically. The oblique view of the foot can help visualize early joint space narrowing. Based on the radiographic findings, the grade of the hallux rigidus can be determined. There are a number of useful grading systems available (Fig. 4.5) (12,13), and one can use a simple system described by Hattrup and Johnson (4):

Grade I: mild to moderate osteophytes formation but good joint space preservation

Grade II: moderate osteophyte formation with joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis

Grade III: marked osteophyte formation and loss of the visible joint space, with or without subchondral cyst formation

Some patients with an essentially normal joint space have severe stiffness and pain, while others with severe disease radiologically have no joint pain but only skin irritation from the prominence. Advanced diagnostic studies could be performed but are rarely indicated.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Technique 1: Cheilectomy

Ankle block anesthesia usually administered

Outpatient procedure

Patient is placed supine, and the extremity is prepared and draped up to the knee.

The extremity is exsanguinated over a sterile, double stockinet using a 4-inch rubber Esmarch bandage.

In most cases, when ankle block anesthesia is administered, the rubber bandage is then wrapped at the ankle level several times for hemostasis. As an alternative, a sterile tourniquet may be used at the ankle.

In patients who have general or spinal anesthesia, a thigh tourniquet may be used.

Preoperative range of motion in the first MTP joint is again tested.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree