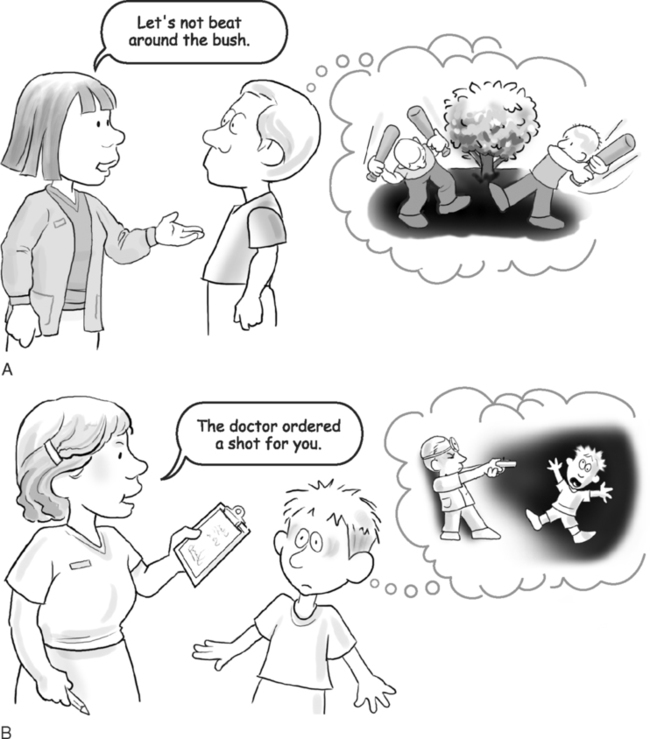

Upon successfully completing this chapter, you will be able to: • Explain how barriers to communication interfere with establishing rapport. • Describe how differences in cultural perspectives affect communication and explain methods to prevent this barrier. • List ways to communicate with patients for whom English is a second language. • Explain how to approach communication with patients who have impairments in hearing, vision, language, or cognition or who are too ill to communicate. • Give examples of how stress and anger interfere with communication and how to relieve the situation. • Give examples of age-related barriers and list ways to work within the age groups. • Explain how personal biases interfere with interaction and list ways to overcome the barriers. • Have you evaluated the patient’s understanding and level of education to determine how to focus the interaction? Are you speaking above or below the patient’s comprehension? Are you sure your message is clearly stated and appropriate for the patient? • Are you and the patient ready to communicate? Is she confused, stressed, or too ill today? Are you distracted, rushed, or not prepared for the interaction? • Does the patient feel pressured? Have your nonverbal cues communicated your lack of time and patience? Have you given him time to organize his thoughts or are you rushing through the exchange? • Does the environment encourage a private, confidential exchange? Is it noisy? Are interruptions a problem? Are others coming and going? Is the room uncomfortable? Is concentration difficult because it is too warm or too cool for comfort? • Does the patient feel confident to confide in you? Does she feel that her information is safe with you? Have you established an appropriate rapport? • Clichéd statements: “Look on the bright side.” “It could have been worse.” These overused statements make patients feel they are not valued as individuals with unique concerns. • Contradicting: “It could not have happened that way.” “Are you sure of what you are saying?” Contradicting implies the patient is not being truthful. If you suspect that what you are hearing is less than the truth, carefully restate your questions for more reliable information. (See Chapter 3, “Gathering Information,” for additional discussion.) • Criticizing: “You know you should have called us as soon as this happened.” Critical statements make patients feel guilty and may build a defensive barrier. • Ridiculing: “That was a dumb thing to do.” As with criticizing, a response such as this stops communication immediately. • Sarcasm: “Oh, great! This is just what you need.” Sarcasm states one thing but implies the opposite. These statements made in a sarcastic tone may be misunderstood, especially if your patient speaks English as a second language. This particular example is confusing since whatever the concern was in this case was certainly not something the patient felt he needed. • Indifference: Patients feel that you do not value their concerns if they suspect you are not focused on communicating. Watch your nonverbal cues and kinesics to keep the channels of communication open. These cues and kinesics include glancing at your watch, yawning, or staring off in the distance while the patient is talking. • Lecturing or offering unsolicited advice: “You know you shouldn’t be smoking.” “Why aren’t you watching your diet?” Do not confuse lecturing with patient education. Lecturing serves no purpose except to scold the patient; patient education can save his life. Idioms are a common form of inexact language that block communication. We take these terms for granted; they add color, humor, and description to our conversations. However, patients may not understand what they mean. Think of times you have used idioms such as those illustrated in Figure 2-1, and how patients may misunderstand or be understandably confused by a common idiom. Within each large culture, such as here in America, are many subcultures (Box 2-1). For instance, North versus South, white collar versus blue collar, young versus old, and so forth, and each defines the behaviors expected of its members. The subcultures listed in Box 2-1 are almost as broad as the major cultures. Within any of these subcultures are also further divisions, such as provinces of China, Native American tribes, and African-American ancestries spread through many regions. All of these factors affect health care based on physical characteristics, dietary habits, genetic heritage, and religious practices. To relate to the groups present in your community, learn as much as you can about the cultures, beliefs, practices, and customary diet. Rather than trying to change these beliefs and customs, try to work within the cultural traditions. If the physician feels that the patient’s cultural practices are affecting his health, it is the physician’s responsibility to discuss this with the patient. • Learn as much as possible about the cultures represented in your area. See these differences as an opportunity to grow in cultural understanding. • Stress the things that most cultures have in common and accept the differences. • Always assume that patients prefer that you use the family name unless you are given expressed permission to use a given name. This is true of all patients, but is especially important in other cultures. • Encourage patients to talk about their illnesses and look for areas of misunderstanding between cultural beliefs and the current diagnosis. • Look for confusion and fear; watch for cues and respond with compassion. Do not ignore culture-based anxiety. Talk to your patients and explain why and how the health care directives help recovery. • Evaluate nonverbal communication by observing proxemics, kinesics, and other cues (see Chapter 1, “Introduction to Communication”). They may be very different from yours. • Treat all patients with respect, concern, and compassion. Try to learn what it is about this illness that this patient sees as most important. It may be different from your reaction to the same illness. • Determine what is important in this culture. What are the religious doctrines and food rituals? How do persons in this culture respond to pain? What is the general level of hygiene? • Find out who makes the decisions. In matriarchal societies, the oldest female makes all decisions; in patriarchal societies, it is the oldest male relative. This patient may not consent to treatment without consulting the authority figure in the group. • Be aware that the dominant authority figure in this patient’s group may accompany the patient and may be the one to whom you direct questions and give instructions. The patient may not be allowed to respond or make decisions without this person’s permission. • Recognize that other societies are not as time-sensitive as Americans. A 10:00 a.m. appointment may mean any time in the morning, or even tomorrow. Your exasperation will not change this behavior, but your understanding will change your exasperation. • Understand that certain cultures avoid eye contact as a matter of respect. Many Asian populations, Native Americans, Arabs, and certain Hispanic groups consider it rude and disrespectful to meet your eyes. For example, Latino women are taught that downcast eyes are a proper response to authority. This is not avoidance; this is tradition. • Recognize that many cultures are less likely than most Americans to “get to the point.” They may see a brief, exact response as abrupt or rude. Rather than “yes/no” or other brief answers, they may give elaborate responses to avoid appearing rude. • Be aware that not expressing pain or illness may be a cultural response. Look for incongruent messages. If the patient appears ill or in pain but denies it, he may feel he cannot acknowledge what he sees as weakness. The outward appearance of strength may be his cultural tradition. • Acknowledge that many cultures are intensely involved with the supernatural and may believe that spirits, hexes, and the like cause illness. In these cultures, the supernatural must be appeased (soothed or satisfied) before healing can begin (Box 2-2). • Incorporate the patient’s folk remedies into treatment if at all possible. In fact, you should ask if he or she has consulted a folk healer. If the answer is “yes,” try to determine what therapies the patient is using. • Learn about the many current medicines and treatments that started as folk or herbal remedies. Talk with your physician about those the patient is using. It may be possible to incorporate them into standard treatment. • Discuss the health care directives to determine whether these will separate the patient from the group’s rituals and traditions. If this happens, you cannot realistically expect compliance. • Be aware of the preferred diet. New Food Guide Pyramids are adapted to many ethnic diets. These are covered in Chapter 5, “Communicating Wellness.” • If you must impose on the patient’s culture by entering private space or by asking probing questions that make patients uncomfortable, apologize and explain why this is necessary. Wealth versus poverty has far-reaching health care significance and is one of the most difficult barriers to overcome. Since most health care workers are middle class, the cultures at opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum are almost as alien as those from distant countries. For example, wealthier patients have better access to health care and generally consult health care providers much earlier than patients who have no permanent physician and who rely on emergency room physicians. The underprivileged are less likely to be well educated and may not understand what they hear in the medical setting. With less self-esteem and self-worth, they are less likely to ask for clarification about anything they do not understand. Wealthy people are usually very concerned with wellness and practice consistent preventive care. Poor people only “fix it” when it is too “broken” to tolerate, since needs other than wellness are far more important, such as a place to live and food to eat (see Chapter 4, “Educating Patients” for discussion of Maslow’s hierarchy). Wealthy people may be treated better by health care professionals than the underprivileged because of issues such as hygiene, presumed compliance, background knowledge of the presenting disorder, and, unfortunately, ability to pay for care. With so many stressors, disadvantaged patients are more likely than wealthy patients to use inappropriate coping mechanisms, such as substance abuse and domestic violence, although neither group is immune to these problems. Poor patients are more likely to see the health care worker as well educated; wealthy patients may see you as someone hired to serve them. If you can think of poverty and wealth as simply other cultures, each with its own language and customs, you will be better able to interact with both groups. Male culture versus female culture also may be significant. Stereotypically, many men are taught to be strong about pain, to “tough it out,” and to see illness as weakness. Conversely, when they do admit to illness, some men regress and expect to be comforted. (Regression as a coping mechanism is covered in Chapter 5, “Communicating Wellness.”) Women, if they have the luxury to do so, may have been taught that illness and weakness are acceptable female reactions. For many generations, women were expected to “swoon” (faint) and actually had “fainting couches” to sink into at the first sight or mention of anything unpleasant. Of course, those who had the luxury of swooning were usually wealthy; there is no record that ladies’ maids were allowed to swoon. Since women as a group have been conditioned by society to be more vocal about their feelings, they frequently are seen as complainers. • When using an interpreter, face both the interpreter and the patient so they can see you and read your communication cues. In this position, you will see both participants and can read their cues as they read yours. Patients need to see your face and may understand more English than they speak. In this position, patients may be able to participate in the exchange. • Use your normal tone of voice. Shouting will not make your words easier to understand and may be seen as anger in some cultures. • Follow the Rule of Fives used for many of the communication barriers that we will discuss in this chapter: sentences no longer than five words, words of no more than five letters. Short sentences and short words are easier to translate. • Keep the exchange simple. For example, ask if the patient has pain, terms such as “discomfort” may be harder to translate. • Ask as many “yes” or “no” questions as possible without limiting the scope of answers. Many patients understand English better than they speak it, and it helps patients feel they are contributing when they can respond even if they do not speak the language well enough to form an extended answer. • Ask one question at a time and rephrase it as many times as necessary for the patient to understand. Do not ask sequential questions, such as, “Have you had nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea?” Break it into several questions. One of the concerns may be overlooked or included incorrectly. • Give patients time to form an answer; some patients mentally translate English into their own language, decide on the response in their language, mentally translate it back into English, then relay it to you in English. Obviously, this is not as simple as processing all of the information in one language. • Avoid slang; it is not appropriate in any exchange and does not translate well to other languages. Remember, too, that idioms are hard to translate. • Be sure you completely understand the patient’s response. Ask for clarification if you are not sure. • Have consents, authorizations, billing forms, brochures, patient education, and so on, printed in the other languages common to your area. Post instructions in restrooms and reception areas in these languages also. • To help establish rapport, learn several phrases in other languages. “Please,” “Thank you,” “Good day,” and other greetings and pleasantries are easy to learn. Patients will appreciate your efforts to communicate and will be more responsive in return.

CHALLENGES TO COMMUNICATION: OVERCOMING THE BARRIERS

CHALLENGES TO COMMUNICATION

Avoidable Barriers to Communication

CULTURAL CHALLENGES

Other Cultural Barriers

LANGUAGE BARRIERS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree