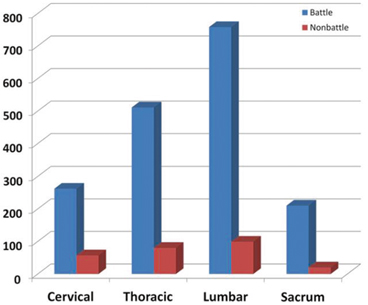

Fig. 13.1

Bar graph comparing the incidence of all spine injuries as percentage of total combat-related injuries between the Korean War and Operation Iraqi Freedom. (Reproduced from Schoenfeld [6]; with permission from Springer)

Epidemiology of Cervical Spine Injury in the US military

Cervical spine fractures are particularly common in younger populations and are often associated with significant associated injuries [14–16]. Several modern studies, primarily from civilian trauma populations, have suggested that risk factors for cervical injury include male sex, white race, lower socioeconomic status, and age 15–30 years [17–21]. Spinal cord injury and fracture data are suggestive that, given the demographics and line of work involved, service members in the US military would be at higher risk for these injuries, which is borne out in the literature [22]. Between the years 2000 and 2009, out of over 13 million active duty service members, a total of just over 4000 cervical spine fractures were documented, with an overall incidence of 0.29 per 1000 person-years. The incidence of fracture-associated spinal cord injury was 0.07 per 1000 person-years, leading to an overall incidence of 7.4 % [19]. Table 13.1 lists the overall incidence rate and risk factors for cervical spine fractures among active duty military personnel [22]. Risk factors for cervical fractures included male sex, white race, enlisted rank, and age 20–29 years, while service in the Marine Corps was identified as the highest incidence rate ratio for fracture associated with spinal cord injury .

Table 13.1

The overall incidence rate and risk factors for cervical spine fractures among active duty military personnel between 2000 and 2009. Male sex, white race, and enlisted rank are all identified as significant risk factors for cervical spine fractures. (Reproduced from Schoenfeld et al. [22]; with permission from Springer)

Category | Number of cases | Person-years | Unadjusted IRa | Adjusted IRR (95 % Cl) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Male | 3645 | 11,795,305 | 0.31 | 1.45 (1.31, 1.61)b | < 0.001 |

Female | 403 | 2,018,028 | 0.20 | N/A | N/A |

Black | 642 | 2,567,557 | 0.25 | N/A | N/A |

Other | 488 | 1,759,176 | 0.28 | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22)c | 0.17 |

White | 2918 | 9,486,600 | 0.31 | 1.21 (1.11, 1.32)c | < 0.001 |

Junior enlisted | 2123 | 6,077,634 | 0.35 | 1.63 (1.34, 1.98)d | < 0.001 |

Junior officers | 276 | 1,354,332 | 0.20 | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28)d | 0.71 |

Senior enlisted | 1488 | 5,506,970 | 0.27 | 1.42 (1.19, 1.70)d | < 0.001 |

Senior officers | 161 | 874,397 | 0.18 | N/A | N/A |

Army | 1613 | 4,976,608 | 0.32 | 1.45 (1.33, 1.59)e | < 0.001 |

Navy | 968 | 3,549,191 | 0.27 | 1.23 (1.12, 1.35)e | < 0.001 |

Air Force | 750 | 3,484,086 | 0.22 | N/A | N/A |

Marines | 717 | 1,803,448 | 0.40 | 1.61 (1.45, 1.79)e | < 0.001 |

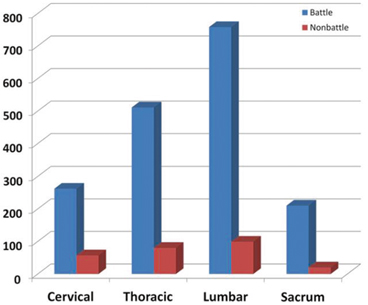

Spine injuries sustained in direct combat during the current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan can be further broken down into epidemiologic categories. Utilizing the Joint Theater Trauma Registry (JTTR), the Skeletal Trauma Research Consortium reported that of 10,979 service members injured between 2001 and 2009, 598 sustained spine injuries, 86 % of which were sustained from direct combat. Of these combat-related spine injuries, 14 % were to the cervical spine. Figure 13.2 shows the anatomic distribution of spine injuries sustained during this time period [23]. From this study, the overall reported incidence of spinal column injuries during Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) is estimated to be 5.45 %, 83 % of which are results of direct combat engagement [22]. Another large, retrospective study examining spine injuries to one Army Brigade Combat Team found that the cervical spine was the more commonly injured spinal segment, occurring in 48 % of all observed spine traumas. The subaxial spine (C3–C7) was most often involved [13]. Blunt trauma to the spine with a diagnosis of cervicalgia or lumbago was the most common type of injury, and 83 % of these injuries were caused by a blast mechanism [13].

Fig. 13.2

Bar graph depicting the anatomic distribution of spine injuries sustained during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom between 2001 and 2009. Cervical trauma accounts for 14 % of all combat-related injuries and 21 % of all noncombat injuries. (Taken from Blair et al. [25]; with permission from Springer)

However, if these data are combined with information regarding spinal injuries in service members killed in action (KIA), the overall incidence rate for spinal trauma rises to 12 %—much higher than previously thought and indeed the highest ever recorded in military medical history [24].

Characterization of Cervical Injuries

As we enter the second decade of the American conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the burden of caring for wounded service members cannot be underestimated. The current conflicts are the longest active conflicts in American history, and as of 2013, more than 50,000 service members have been injured [26]. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly apparent that injuries to the spine—either acute traumatic injuries or chronic spinal pain—are significant contributors to this burden [27]. Patients with noncombat spine pain evacuated from theater have a less than 20 % likelihood of returning to duty [13]. It is important to recognize, therefore, that while direct trauma to the cervical spine is a significant cause of wartime morbidity and mortality, it is not the only debilitating cervical complaint observed during these long wars.

Nontraumatic Cervical Spinal Pain

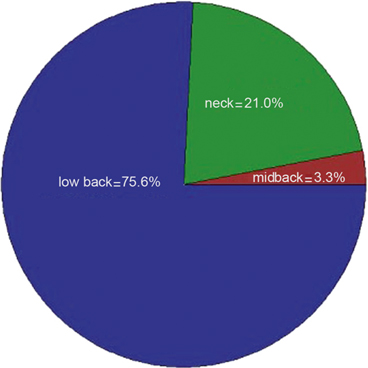

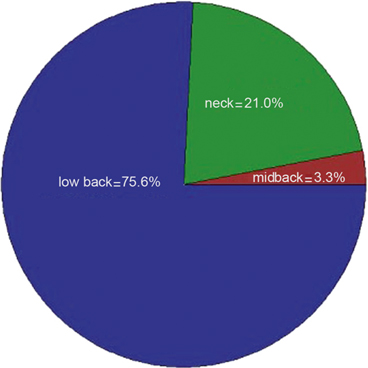

By the end of the Vietnam conflict, non-battle injuries had surpassed all other disease categories as the leading cause of service member attrition [28]. In all subsequent conflicts, as the mortality rate from combat injury has steadily decreased, return to service for injured service members has become more important for maintenance of force readiness. Chronic spinal pain has become increasingly more apparent as a significant cause for hospitalization and medical evacuation from theater: over a 3-year period, almost 2500 OIF/OEF service members were medically evacuated for “spinal pain,” comprising 7.2 % of all evacuees [29]. Figure 13.3 shows the breakdown of spinal pain by region, with neck/cervical pain representing 21 % of all complaints [30]. There is some evidence suggesting that deployment to a combat zone alone increases the risk of worsening spinal pain [26]. One large epidemiologic study found that of 374 service members evacuated from theater for cervical pain, only approximately one third could identify an inciting event, the most common of which was prolonged driving [31]. Among spine pain evacuees from OIF and OEF, 84 % of service members with neck pain had primarily radicular symptomatology, suggesting that a primarily neuropathic etiology such as a herniated disc is the cause of the debilitating pain [30, 32]. Of course, the risk of spinal pain is likely multifactorial in its etiology, but its effect on force readiness and combat operations cannot be understated .

Fig. 13.3

Pie chart showing the breakdown of spinal pain by region, with neck and cervical pain representing 21 % of all spinal complaints. (Taken from Cohen et al. [30]; with permission from Springer)

Cervical Trauma

Direct injuries to the cervical spine remain devastating realities of the current conflicts, and they do not occur in isolation. A recent retrospective study has shown that for service members sustaining any spinal injury, there is an average of 2.8 separate spine injuries per patient [22]. An understanding of the types of injuries and associated patterns sustained by service members in the current conflicts would not be complete without a discussion of the mechanisms by which a majority of these injuries occur, their other associated injuries, and their significant morbidity and mortality.

Mechanism of Injury

As previously noted in this chapter, unconventional warfare tactics, including guerilla warfare and the use of IEDs, have been the primary modes of counterattack employed by enemy combatants. While gunshot wounds and motor vehicle collisions (MVC) remain important causes of cervical spine trauma, injuries secondary to IED blast have comprised a higher percentage of combat wounds than in any other conflict in history [33]. Advances in individual body armor as well as up-armored vehicles have increased overall survivability, but injuries remain severe [13]. Complex blast injuries have been extensively studied and have been categorized into a progressive spectrum that includes primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary effects [34–37]. Table 13.2 breaks down each individual type of blast injury by effect [38]. Specifically, injuries to the spine appear to be primarily secondary to blunt- or crush-type mechanisms rather than primary, overpressure patterns [38]. A large retrospective review of the JTTR showed that of all documented evacuated combat casualties between 2001 and 2009, 51 % of patients sustaining combat-related spine injuries were by a blunt mechanism, whereas 27 % sustained penetrating injury to the spine. However, no differentiation is made between penetrating injuries secondary to IED blast or, for example, gunshot wounds. The vast majority of these patients sustained multiple injuries to multiple anatomic spine locations. Of patients injured by blunt mechanisms, 24 % sustained isolated cervical spine injury, while 27 % of those patients injured via penetrating mechanism sustained isolated cervical injury. Cervical fractures, specifically, were sustained in 18 % of blunt injuries, with 21 % sustaining cervical fractures in the penetrating trauma group. Transverse process and compression fractures were the most commonly observed fractures in the blunt trauma group (43 %). Spinal cord injuries comprised 17 % of the total patients sustaining spine trauma, with 61 % of those injuries caused by a penetrating mechanism. Patients sustaining penetrating injuries were 3.8 times more likely to have a spinal cord injury than those caused by a blunt mechanism [42].

Table 13.2

A tabular breakdown of specific injury patterns secondary to individual blast classification. (Taken from Kang et al. [38]; with permission from Springer)

Classification | Description | Injury pattern |

|---|---|---|

“Overpressure” injury “Implosion” occurs at time of contact with body surface, blast front rapidly compresses gas-filled organs and then near instantaneously reexpands as blast front passes “Spalling” occurs as blast front propagates through body, significant shear and stress forces because of differences in tissue density of adjacent organs and tissue at air-fluid interfaces causes forcible explosive movement of fluid from more dense to less dense tissues | Implosion injuries Auditory shift (2 psi) Tympanic membrane rupture (5–15 psi) Lung injury, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, air embolism, intestinal emphysema (30–80 psi) 50 % chance of death (130–180 psi) Probable death (200–250 psi) Spalling injuries TBI Gastrointestinal tract injury Tearing of organ pedicle Eye injury | |

Ballistic injury from primary bomb casing fragments; also from secondary fragments (i.e., environmental material, metallic debris, glass); become projectile after energized by explosion Fragments strike the body and cause penetrating injuries; can also cause traumatic amputations Variable velocity depending on size/shape of fragment and distance from explosion epicenter; rapid deceleration because of aerodynamic drag “Shimmy” effect from irregularly shaped fragment contacts body and exhibits tumbling; increases amount of local tissue damage | Penetrating injury Traumatic amputation Laceration TBI | |

Tertiary [5, 24, 28] | Whole body translocation Blast wave energizes and propels individual to tumble along the ground or thrown through air to strike hard surface Large object may become projectile and impact individual causing significant blunt or crushing injuries < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|