Cervical Spinal Stenosis

Eileen A. Crawford

Nader M. Hebela

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Cervical spinal stenosis is the narrowing of the overall space available for the spinal cord within the spinal canal. The spinal canal is defined by its borders, anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. The vertebral bodies and intervertebral disks are located anterior to the spinal cord and overlying dura mater. The ligamentum flavum and laminae of the vertebrae define the posterior borders of the spinal canal. On either side, just lateral to the spinal cord, the pedicles connect the anterior and posterior elements, defining the lateral extent of the spinal canal.

Cervical spinal stenosis may be congenital, resulting from short pedicles, which essentially create the overall diameter of the spinal canal. Shortened pedicles limit the overall space available for the cord by decreasing the distance between the most anterior limits of the spinal canal (the posterior edge of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral disks) and its most posterior limits (the anterior aspects of the laminae).

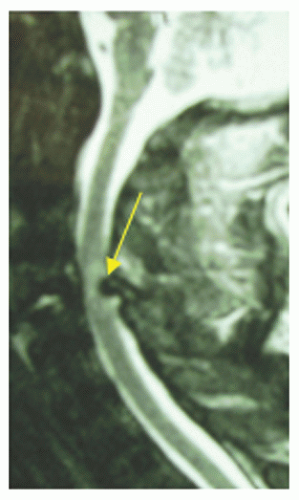

More commonly, cervical spinal stenosis may result from age-related degenerative changes that cause compression on the spinal cord from within the spinal canal. Multilevel disk bulging, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, loss of disk height, and associated degenerative changes will result in narrowing of the space available for the spinal cord within the spinal canal.

Degenerative disk disease is thought to be the inciting event. Loss of disk height results in abnormal motion within the functional spinal canal. As a result, the body responds by attempting to limit this abnormal motion. Thickening of the ligamentum flavum will increase the overall stiffness between the posterior laminae. Osteophyte formation, the formation of bone due to degenerative changes, may be the result of the increased stresses experienced by the vertebral bodies. The degenerative changes within the disk itself result in bulging, which causes cervical spinal stenosis when combined with these other changes.

Patients present complaining of a variety of symptoms associated with degenerative changes in the cervical spine as well as neurologic symptoms. Neck pain, trapezial pain, and pain with cervical spine range of motion are common. Patients report pain that is typically degenerative in nature, worse in the mornings and with start-up activity, improving with motion during the course of the day. They may report increasing pain at night and often describe having to change their normal sleeping position. Neurologic symptoms include periscapular radicular pain, just medial to the shoulder blade, and radiating pain into the shoulder, arm, hand, and fingers. Patients may report numbness and tingling in the affected upper extremity. Unlike cases of paracentral disk herniations, patients with stenosis usually present with bilateral upper extremity radicular pain and paresthesias that are not necessarily consistent with a dermatomal pattern. The upper extremities are almost always more affected than the lower extremities for new-onset complaints.

It is important to distinguish between radicular pain and paresthesias and symptoms associated with cervical myelopathy. In addition to pain, numbness, and tingling in the upper extremities, patients with myelopathy also report difficulty with

fine motor functions such as using keys, writing, or buttoning a shirt. Not uncommonly, patients who are myelopathic experience gait and balance problems, often leading them to use an assistive walking device such as a cane or walker. They will often report that their balance does not feel as secure as it once was. In contrast to lumbar stenosis, cervical stenosis with myelopathy affects proximal muscle groups of the lower extremities more than distal muscle groups. Bowel and bladder dysfunction is rare in cervical stenosis and suggests advanced disease.

fine motor functions such as using keys, writing, or buttoning a shirt. Not uncommonly, patients who are myelopathic experience gait and balance problems, often leading them to use an assistive walking device such as a cane or walker. They will often report that their balance does not feel as secure as it once was. In contrast to lumbar stenosis, cervical stenosis with myelopathy affects proximal muscle groups of the lower extremities more than distal muscle groups. Bowel and bladder dysfunction is rare in cervical stenosis and suggests advanced disease.

CLINICAL POINTS

Cervical stenosis may be degenerative or, less commonly, congenital in etiology.

Pain may be diffuse, affecting the neck, back, shoulders, and both upper extremities.

Patients with myelopathy often describe difficulty with balance and fine motor tasks.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough upper and lower extremity examination helps gauge the severity of the patient’s complaints. Neck range of motion may be painful or limited in extension in cases of cervical stenosis. Asking the patient to rise out of a seated position and rise onto the heels and toes is a quick and simple functional assessment of lower extremity strength.

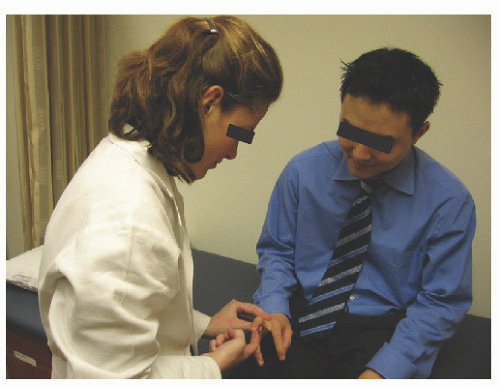

Manual muscle strength testing of all peripheral upper extremity muscles as well as reflex testing helps both to gauge functional strength and to assess for any abnormally brisk reflexes suggestive of cervical spinal cord compression. Eliciting a brachioradialis reflex (C6) of rapid wrist extension while actually performing a biceps reflex text (C5) is known as a “drifting reflex” and should raise concern for an upper motor neuron lesion, including but not necessarily limited to cervical spinal stenosis. A positive Hoffmann sign (involuntary thumb and index finger flexion with flicking the distal end of the long or ring finger) is also very suggestive of cervical stenosis (Fig. 9-1). Atrophy of the intrinsic hand muscles may be seen with both lower cervical radiculopathies and myelopathy.

FIGURE 9-1. The Hoffmann sign is elicited by dorsiflexing the distal interphalangeal joint with the phalanx in extension. Extending the neck will narrow the spinal canal and may increase the chances of a positive Hoffmann.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|