22 Cervical and lumbar spine

Cases relevant to this chapter

17–18, 24, 28–31, 33–34, 50, 74, 78

Essential facts

1. Intervertebral disc degeneration is a normal finding in people over the age of 40 years; radiographic abnormalities of disc space narrowing and bone spurs around the discs and facet joints have little clinical relevance.

2. Cervical cord compression can present in young to middle-aged patients due to disc herniation, but it is more likely to occur in older patients due to bone thickening around degenerate joint margins.

3. Atlanto-axial involvement occurs in 50% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who have neck problems, but all levels can be affected, from occiput to cervico-thoracic junction.

4. Mechanical pain or ‘simple back pain’ occurs in 80% of the population; 80% will resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks and in 80% no clear cause can be identified.

5. Radiological investigation of back pain is most helpful in patients aged over 50 years (looking for metastases), in those aged under 20 years (looking for adolescent disc herniation, spondylolysis or benign tumour), or if inflammatory spinal disease is suspected.

6. The following are ‘red flag’ features of back pain: violent trauma; constant, progressive non-mechanical pain; thoracic pain; presentation under 20 or over 55 years of age; previous history of carcinoma; use of systemic steroids; drug abuse or HIV infection; systemically unwell; weight loss; lumbar stiffness; widespread neurological signs; and structural deformity.

7. Some 90% of disc herniations resolve spontaneously by dehydration and resorption of herniated material; the diagnosis is clinically obvious and there is no benefit in rushing to special investigations.

Degenerative conditions of the cervical spine

Cervical pathology is largely due to degenerative disease. Intervertebral disc degeneration is the norm over the age of 40 years and radiographic evidence of disc space narrowing and bone spurs around the margins of the discs and facet joints has little clinical relevance. The presence of disc herniations or osteophytes can cause nerve pain that is felt down the arm (brachialgia) with altered sensation in the corresponding dermatome and weakness in the corresponding myotome. The commonest level affected is C5/6; this affects the sixth cervical nerve (C6) so that there is numbness in the dermatome affecting the index finger and thumb, weakness of the biceps muscle and a reduced biceps reflex. The C6/7 level is the second commonest and presents with seventh cervical nerve compression symptoms and signs (Fig. 22.1). Pain is reproduced by lateral rotation to the symptomatic side (Spurling’s sign) or with axial compression produced by pressure on the patient’s head.

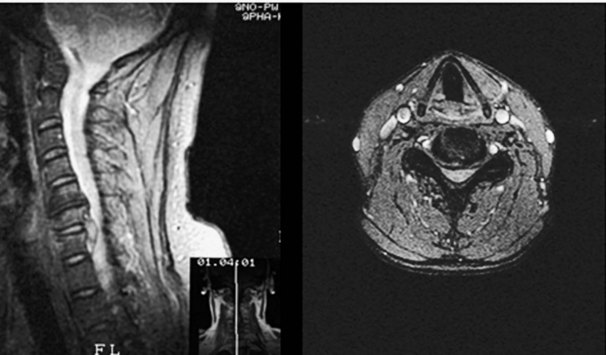

Most cervical nerve compression symptoms improve with time, but there is a place for physiotherapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and epidural steroid injections. The best investigation is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 22.2). Because pathology is common, even in subjects who have no symptoms, the scan findings must be carefully correlated with the clinical findings. In cases where the symptoms fail to improve with time and conservative treatment, a cervical discectomy can be performed. This procedure is carried out through an anterior approach, which gives excellent access to the intervertebral disc. The disc is excised completely and, after decompression of the affected nerve, the level is usually fused using a bone graft from the iliac crest or a bone substitute, such as tricalcium phosphate (Fig. 22.3). The procedure is usually straightforward and excellent results can be achieved. There is a risk of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which can induce hoarseness. The airway needs careful observation afterwards and a drain is used to reduce the risk of haematoma formation.

Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine

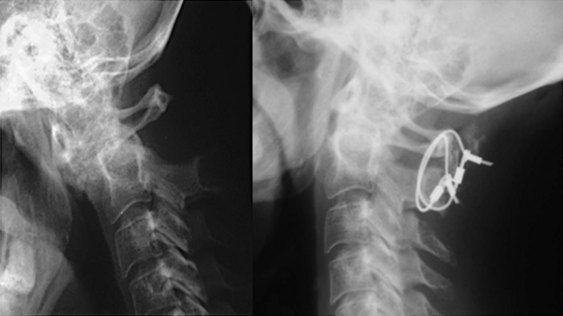

Cord dysfunction develops and manifests as impairment of hand function and heavy legs. If unchecked, the patient becomes a wheelchair-user and the condition may even cause sudden death (see Chapter 1). Plain radiographs look unremarkable, but flexion/extension views (Fig. 22.4) unmask the instability and show excessive movement of the atlas on the axis (>3 mm). The condition is treated by posterior fusion of C1/2 with bone grafting and internal fixation using wires, screws or a combination of these methods.

The Ranawat grading of myelopathy is the most commonly used method for assessing the severity of cervical spine involvement and the outcome after treatment (Box 22.1). Operative treatment does not reverse the neurological effects fully, but it is often possible to produce improvement by one Ranawat grade. Although myelopathy is the most compelling reason to operate on the cervical spine, patients without neurological compromise may require operative treatment for painful instability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree