Cemented Acetabular Components

Matthew C. Morrey

Bernard F. Morrey

Introduction

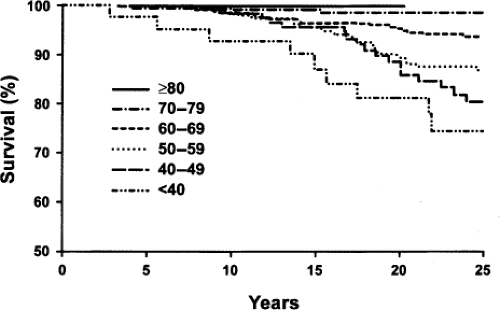

Cement fixation of the acetabular component for primary replacement has been all but abandoned except for the geriatric patient in the United States and other parts of the globe. This has occurred in spite of the data, generated from large registries and from large practices such as the Mayo Clinic, which show that the cemented acetabular component performs as well as, if not better than, the modular cementless cups which have essentially captured the market (Fig. 53.1). Indeed, data published from national databases and registries document that cemented cups outperform uncemented ones (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15). Although the femoral stem design has gradually resulted in better longevity of the uncemented stem, this has not yet been shown to be the case with the cup, for any age, nor for different diagnostic categories (11,12). What is well documented is that the use of modular acetabular components has increased the clinical manifestations of wear-induced osteolysis (16). Fortunately, the introduction of highly cross-linked polyethylene appears to have lessened or perhaps even negated much of this concern (12) while fragmented cement continues to be associated with osteolysis (17). Hence, modular cups are preferred in most practices around the world today, and cementing polyethylene cups has been relegated to use in limited revision circumstances or in patients greater than 75 years of age (18). The utility in revision allows for the simple replacement of a worn poly liner fixed with cement when the capture mechanism of a retainable well-fixed shell is not functional. A second circumstance is when the need occurs to employ a polyethylene liner of a different manufacturer into that of the well-fixed metal shell.

Experimental and Design Considerations

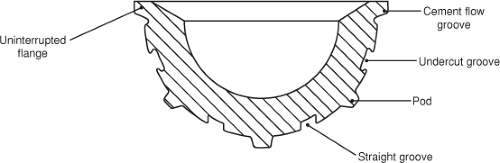

The history surrounding cemented cup development is rather colorful and interesting and findings relevant to the present usage of the cemented cup can be seen. Implant design clearly influences component performance and survival (Fig. 53.2) (19,20,21,22,23,24). Some features, such as an elevated rim might be expected to cause increased loosening and wear, but this has not pro4ven to be the case to date (25).

Cup and Cement Thickness

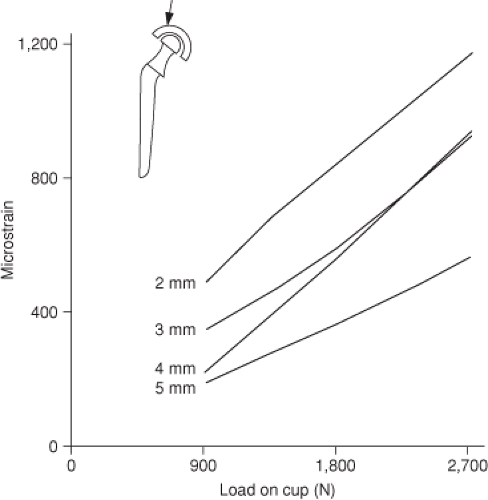

Increasing the thickness of UHMWPE causes a proportionate decline in microstrain, especially at the articular surface, thus favoring the thicker polyethylene component (Fig. 53.3) (26). However, this issue appears to be less critical with the more recently developed highly cross-linked polyethylene.

Cement thickness however, continues to remain a concern with the current use of the thinner liner fixed with thin cement mantles. Studies have shown the thicker cement mantles not only decreases stress at the interface, but also creates more uniform stress within the poly itself (Fig. 53.4). It should be noted, however, that this results in a difficult compromise, as those components designed with polyethylene pegs incorporated in the cup suffered from significantly higher failure rates in spite of their creation of more uniform cement mantles (20).

Cement thickness however, continues to remain a concern with the current use of the thinner liner fixed with thin cement mantles. Studies have shown the thicker cement mantles not only decreases stress at the interface, but also creates more uniform stress within the poly itself (Fig. 53.4). It should be noted, however, that this results in a difficult compromise, as those components designed with polyethylene pegs incorporated in the cup suffered from significantly higher failure rates in spite of their creation of more uniform cement mantles (20).

Head Size

The calculated surface contact stress for a simulated 28-mm head system is less than that for the 22-mm head. As the poly thickness increases from 0.1 to 0.5 mm, surface stress decreases proportionately but not linearly (26). Hence, in the past, if larger head diameters such as 32 mm were desired for stability, care was taken to ensure that the polyethylene was at least 8 mm thick. This requirement is not felt to be necessary for the highly cross-linked material and this is responsible for the trend to employ larger head diameters in an effort to enhance stability—hopefully with the impunity attributed to the material properties and superior wear characteristics of the highly cross-linked polyethylene. (See Chapter 65 on highly cross-linked poly.)

Metal-Backed Acetabular Implant

Before the development of the current modular metal/poly implant, efforts were made to enhance performance of the all-polyethylene implant by introducing a metal-backed composite. Studies revealed a theoretical advantage to lessen the “buckling effect” of the all-poly cup with central loading (27,28,29,30). Furthermore, the increased stresses in the PMMA that occur after subchondral bone removal are theoretically lessened by the use of a metal-backed implant (27,28,31). However, as so often occurs, when the theoretical advantage was tested by inserting such cups with cement fixation, the clinical performance was measurably inferior (21,32,33,34). One report places the 10-year survival of cemented metal-backed devices to only 42% (33) (Fig. 53.5). The cemented metal-backed poly cup was subsequently abandoned in short order.

Indications

The clinical outcomes of cemented noncross-linked cups in patients less than 30 (18,35,36,37), all show poor survival. Therefore, today, as noted above, most would agree that the indications for a primary cemented all-poly cup would employ highly cross-linked, UHMWPE in patients older than 70 or 75 years of age (8,15,38). However, it must be noted that a meta-analysis published in 2007 reveals that survival of the cemented cup outperforms that of the modular uncemented construct, for all diagnoses and at virtually all age groups, based on designs used at the time of the study (13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree