Chapter 155 Celiac Disease

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

• A chronic intestinal malabsorption disorder caused by an intolerance to gluten

• Bulky, pale, frothy, foul-smelling, greasy stools with increased fecal fat

• Weight loss and signs of multiple vitamin and mineral deficiencies

• Increased levels of serum antiendomysium and/or transglutaminase antibodies

General Considerations

General Considerations

Celiac disease, also known as nontropical sprue, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, or celiac sprue, is characterized by malabsorption and an abnormal small intestinal structure that reverts to normal on removal of dietary gluten. The protein gluten and its polypeptide derivative gliadin are found primarily in wheat, barley, and rye grains. Symptoms most commonly appear during the first 3 years of life, after cereals are introduced into the diet. A second peak incidence occurs during the third decade, and although celiac disease is often thought of as a disease diagnosed early in life, more diagnoses are made in adulthood than in childhood.1

That the prevalence of celiac disease has increased dramatically, is undeniable and this is not solely because of increased detection. Until a few decades ago, celiac disease was believed to be relatively rare (approximately 1 case in 5000 within the United States). Now, however, celiac disease is thought to affect approximately 1% of most populations, but it remains largely undiagnosed.1–3 Undetected celiac disease carries with it an increased mortality, indicating that widespread screening may be economically justified.

Chemistry of Grain Proteins

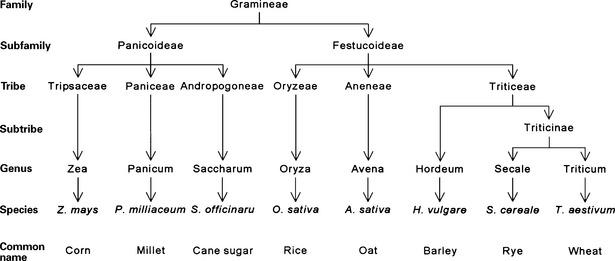

Gluten, a major component of the wheat endosperm, is composed of gliadins and glutenins. Only the gliadin portion has been demonstrated to activate celiac disease. In rye, barley, and oats, the proteins that appear to activate the disease are termed secalins, hordeins, and avenins, respectively, and prolamines collectively. Cereal grains belong to the family Gramineae. The closer a grain’s taxonomic relationship to wheat, the greater its ability to activate celiac disease. Rice and corn, two grains that do not appear to activate celiac disease, are further removed taxonomically from wheat. The taxonomic relationship of the grains is shown in Figure 155-1.

Gliadins are single polypeptide chains that range in molecular weight from 30,000 to 75,000, with a high glutamine and proline content. Gliadins have been divided into four major electrophoretic fractions: alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and omega-gliadin. Alpha-gliadin is believed to be the fraction most capable of activating celiac disease, although beta- and gamma-gliadin are also capable of doing so. Omega-gliadin does not appear to activate the disease, although it has the highest content of glutamine and proline. Gliadin that has been subjected to complete hydrolysis does not activate celiac disease in susceptible individuals.4

Pathogenesis

Celiac disease appears to have a genetic etiology, since it is associated with specific HLA molecules—HLA-DQ2 in 95% of patients and DQ8 in the remainder. These gene loci are believed to be linked to the immunologic recognition of antigens and specific T-cell–regulated immune responses.

Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of celiac disease. Currently, the most likely relates to abnormalities in the immune response rather than some “toxic” property of gliadin. Sensitization to gliadin occurs both in humoral and cell-mediated immunity, and it appears that T-cell dysfunction is the main factor responsible for the enteropathy.4 A number of circulating antibodies that are specific for celiac disease, particularly antiendomysial antibody (AEA), have been identified. These serologic markers have been used successfully to screen patients and to estimate the true prevalence of celiac disease in the general population. The discovery that tissue transglutaminase (tTG) is the autoantigen for AEA led to the development of an improved enzyme-linked assay using recombinant tTG, which has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific for celiac disease. Tissue transglutaminase is a ubiquitous, predominantly cytoplasmic enzyme that can be released extracellularly, particularly in response to tissue wounding and stress. The observation that anti-tTG antibody titers fall and can become undetectable during a gluten-free diet suggests that tTG-gliadin complexes stimulate gluten-specific T cells to induce anti-tTG antibody production. T and B cells likely recognize different parts of this antigen complex, with T cells reacting to the smaller gliadin peptides and B cells responding to the larger tTG enzyme.4

Interestingly, breastfeeding appears to have a prophylactic effect, and breastfed babies have a decreased risk of developing celiac disease.5,6 The reduced risk of celiac disease was even more pronounced in infants who continued to be breastfed after dietary gluten was introduced. Not surprisingly, the risk of celiac disease was greater when gluten was introduced in the diet in large amounts than when introduced in small or medium amounts. The early introduction of cow’s milk is also believed to be a major etiologic factor.7 Research in the past few years has clearly indicated that breastfeeding, along with delayed administration of cow’s milk and cereal grains, are primary preventive steps that can greatly reduce the risk of developing celiac disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree