48. Case histories illustrating integrated diagnosis and treatment

Chapter contents

Introduction382

Case history 1 – Howard383

Further examples of integrated diagnosis389

Case history 2 – Patricia389

Case history 3 – Ellena391

Conclusion393

Introduction

The previous chapter described the similarities and differences between Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture and TCM and the strengths and weaknesses of each. This chapter will now take the practitioner through the main stages of an integrated diagnosis and treatment. The purpose of integrated treatment is to give patients a chance to thrive with minimum intervention from treatment. Some general principles for the practitioner to follow when integrating the two styles of treatment are as follows.

• Use the first treatments to confirm the CF. Diagnosis is only a working hypothesis until confirmed by the patient’s response to treatment. Because treatment on the CF will affect many other treatment principles, the practitioner often concentrates on using the first few treatments to resolve any areas of uncertainty about it. At this stage the practitioner is therefore less likely to treat other obvious pathologies, such as Blood, yin or qi deficiency.

• Clear any blocks to treatment if they are severe enough to hold back progress. Aggressive Energy, Possession, Husband–Wife and Entry–Exit blocks should always be cleared first.

• Clear full conditions caused by Pathogenic Factors, Phlegm and Blood Stagnation if they are severe enough to stop treatment on the CF from being successful. If the condition is overwhelmingly full, for example an acute infection, the CF should not be treated at all. The practitioner needs to find a balance between clearing and tonifying when a patient has a mixed condition, i.e. full conditions with marked underlying deficiencies. Because the presence of Pathogenic Factors is often diagnosed more easily than the CF and other deficiencies, there is a tendency for some practitioners to concentrate on clearing pathogens to the detriment of tonifying.

• If treatment on the CF is not generating sufficient improvement in certain signs and symptoms, more treatment principles can be added. Minimum intervention remains a guiding principle.

• If necessary, consider treatment principles that differentiate whether the CF is more yin or yang deficient or has any substance pathologies such as qi or Blood deficient or stagnant.

These principles of integration will be demonstrated using case histories of some patients who have benefited from treatment.

The stages of making an integrated diagnosis and treatment are as follows:

• take the case history – make rapport, ask specific questions and assess the emotions

• make a diagnosis

• draw a diagram of the diagnosis

• formulate treatment principles

• simplify and prioritise the treatment principles

• form a treatment strategy

• decide on points

• carry out the treatment

Case history 1 – Howard

Introduction and making rapport

Howard was 58 years old and married with two grown-up children. The elder was from a previous marriage. The practitioner’s first impression of him was of a friendly and amicable person. He was of medium height and slightly overweight. Howard was out of breath climbing the flight of stairs to the treatment room. He commented as he sat down that he could feel his heart beating from the climb. His main complaint was asthma.

The practitioner first asked Howard to say something about himself – this was in order to get to know him and gain rapport. Howard responded by telling her that he was a school caretaker and that he had been in his job for 25 years and loved it.

Howard was chatty and warm and laughed a lot. He was often making jokes – sometimes at his own expense. (The practitioner noticed that when given respect or when talking about some poor treatment he had received for his asthma, he would laugh rather than express grief, anger or other emotions. At other times his joy would drop, especially when the practitioner stopped chatting and wrote some notes. At these times he seemed momentarily sad and vulnerable. His joy would then come up again when the conversation recommenced.)

Main complaint

The diagnosis continued with the practitioner asking him for more specific details about his main complaint. The asthma began over 20 years ago. He had had a bout of bronchitis with frequent coughing so had decided to give up smoking. A couple of days later he developed bronchial asthma and had had it ever since. ‘Maybe I should start smoking again!’ he quipped.

He described feeling as if a ‘brick’ was sitting across his chest. He felt as if couldn’t get any more air into his lungs as they felt so full and congested. Occasionally he would bring up some thick white phlegm. He also said that his chest was much worse when lying down and he slept with at least three pillows most of the time.

The asthma was controlled by inhalers but as soon as he had a cold or flu it would go to his chest and he would often have a full-blown asthma attack. The last one had been two months ago and he had been taken into hospital and ‘pumped full of steroids’. He admitted that he was scared of this happening again and that was why he had come for treatment. (The practitioner judged that considering the seriousness of the situation that the way he expressed his fear was appropriate.)

Questioning the systems

Howard said that his sleep was ‘dreadful’. It was light and the smallest thing would wake him, even the birds singing. He got off to sleep easily but would then wake at 2–3 a.m. and couldn’t get off again. He would then go to sleep after what seemed like a long time and would wake with a muzzy head. (When the practitioner offered him sympathy about his poor sleep Howard accepted it.)

Howard said his appetite was ‘too good’ and he loved to eat. He would often consume dairy products and had a hot milky drink before bed, ‘to help him sleep’. He would often bloat after eating and would have loose stools which didn’t have a strong odour.

Howard also said he had poor energy and said he felt ‘totally worn out’. He loved his job but whereas once it had been easy, it now exhausted him and he was wondering whether it was time to retire.

The practitioner continued to ask Howard specific questions about his health such as thirst, urination and perspiration, and wrote down all of Howard’s answers. At the same time she assessed how Howard responded emotionally to her questions.

Personal history

She also asked Howard about his health history, his family health and his personal history. This included questions about areas such as his childhood, emotional stresses, difficult phases in his life and relationships, as well as which areas of his life were most problematic for him. These were all important to get to know Howard as a person. The questions are also important to get a sense of the balance of a patient’s emotions. This is easier when they are talking about difficult issues in their life than when describing less problematical topics like perspiration, urination, etc.

Howard described having a happy childhood: ‘I always had lots of friends and I could always make them laugh.’ He also said that he was generally happy with his life at present but that he thought he suffered from Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) and got quite depressed in the winter: ‘We’re going to move to Italy in the winter months.’ He said he thought it had got worse as he became older. When questioned more about this he said things were generally fine and that he didn’t wish to dwell on his difficulties. He did, however, mention in passing that his elder daughter from his first marriage was dependent on heroin and this caused him much pain and sadness. He had tried to help her but she didn’t seem to want to help herself. (He looked very sad when talking about this issue. The practitioner noted that she might talk with him some more about this later.) When asked about his current wife, he laughed and said everything was ‘fine’, but his eyes and facial expression belied this.

Howard’s pulses

Howard’s pulses all felt deficient and the practitioner wrote down this pulse picture:

| Left | Right | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SI –1 | Ht –1 (Floating) | Lu – ½ | LI – ½ (Floating) |

| GB – ½ | Liv – ½ | Sp – 1½ | St – ½ (Slippery) |

| Bl – ½ | Kid – 1½ (Deep) | PC – 1½ | TB –1½ (Deep) |

Tongue diagnosis

Howard had a pale, swollen tongue with a midline crack going to the tip. At the rear of the tongue he had a sticky white tongue coating. The tip was redder than the main tongue body.

Physical examination

Having taken Howard’s pulses and looked at his tongue, the practitioner carried out other parts of the physical diagnosis such as feeling his three jiao, palpating the front mu and back shu points, testing the Akabane and observing his colour, sound and odour. After the diagnosis was completed and Howard had left, the practitioner went over all the information she had written down. She then wrote up the diagnosis, including drawing a diagnostic diagram.

Diagnosis

Forming a diagnosis

The practitioner knew that she needed to diagnose Howard’s whole condition in order for both the root and the manifestation of his problem to improve. This meant that she should identify all of the patterns present. This included his CF as well as any syndromes that were present.

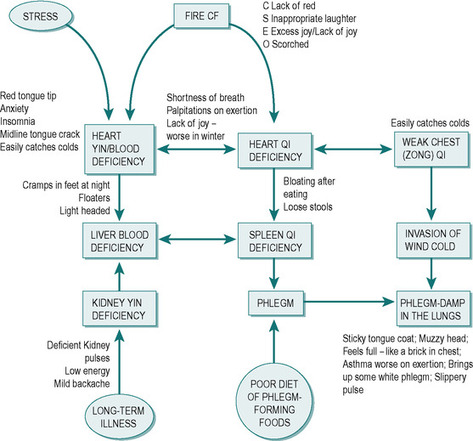

She put these together and drew a diagram. The purpose of the diagram was to give the practitioner an overview of the diagnosis. The diagram could connect Howard’s ‘patterns’ aetiologically and bring in specific internal, external and miscellaneous causes of various patterns. The practitioner also included the signs and symptoms supporting each pattern. This allowed for easier monitoring of Howard’s progress.

Howard’s CF

The practitioner opted for Howard being a Fire CF. This is because he laughed inappropriately and showed excess joy even when he might have become angry, or suffused with grief. He also showed appropriate fear and accepted sympathy appropriately. At the same time he would drop into sadness and seemed vulnerable and uncertain when the practitioner stopped chatting.

Howard did not want to dwell on his difficulties when questioned. Although he admitted to having SAD in the winter months he did not wish to talk about this and he mentioned but didn’t talk in any depth about his daughter’s dependency on heroin. He preferred to laugh, chat and joke. Keeping his cup ‘half full’ was probably a positive way for him to deal with his difficulties – but this was to the detriment of looking at his whole situation and was probably contributing to his underlying depressed condition. To back up the diagnosis of Fire, the practitioner saw a lack of red colour by the side of Howard’s eyes and smelt a scorched odour.

The practitioner thought that some of Howard’s treatment would need to be directed towards the level of his spirit. She hoped that when Howard felt stronger and trusted her he would probably be able to open up and talk more about himself.

The practitioner also considered whether Howard was suffering from possession, had a Husband–Wife imbalance or had an Entry–Exit block. She did not think that any of these were present.

Making a diagram

Figure 48.1 shows the diagram drawn up by the practitioner. The oblong boxes indicate the main patterns. The oval boxes indicate aetiology and the main signs or symptoms are written next to the boxes. The boxes are joined up by arrows that indicate in which direction the patterns probably affect each other – sometimes the arrow travels in two directions, indicating that the patterns are both affecting each other.

|

| Figure 48.1 |

The diagram shows all of Howard’s patterns including the CF. Because the CF underlies all of the other patterns, it is placed at the top of the diagram. Usually (but not always) the CF and the other patterns will involve some of the same Organs. In this case Howard’s constitutional imbalance in Fire has led to Heart qi and Heart yin deficiency. The diagram also describes how the Phlegm–Damp has probably been formed. The cause is likely to be from a combination of a number of factors which are:

1 the constitutional Fire imbalance, which has led to a weak chest and zong qi

2 a poor diet with too many Phlegm-forming foods

3 colds (invasions of Wind–Cold) which easily go to the chest

Treatment planning

Forming treatment principles

The next stage in the diagnosis is for the practitioner to form treatment principles. These inform the practitioner in the choice of points. The main treatment principles involved in a Five Element diagnosis would be to ‘Treat the CF’ or to deal with a block such as Aggressive Energy, Possession, Husband–Wife imbalance or Entry–Exit block.

A TCM practitioner would use treatment principles to decide whether to tonify the deficient patterns and to clear full ones.

Putting these together into an integrated diagnosis allows the practitioner to have an overview of all of the treatment priorities – so the first stage of planning treatment is to list all possible treatment principles:

• treat Fire CF

• tonify Heart qi

• nourish Heart yin

• tonify zong qi

• clear Wind–Cold when present

• nourish Liver Blood

• tonify Spleen qi

• clear Phlegm

• clear Phlegm–Damp from the Lungs

If the practitioner used all of the patterns listed in the boxes above the result would be confusing. There would be far too many treatment principles. The next stages are to simplify and then prioritise the treatment principles.

Simplifying the treatment principles

In order to simplify the treatment principles, the practitioner eliminated all treatment principles that she believed to be unnecessary. Most of these were ones she expected to be resolved when dealing with other treatment principles.

Some of the treatment principles could easily be simplified. For example, on reflection ‘nourish Liver Blood’ could be taken out as the Blood deficiency had probably come from the Heart Blood deficiency (more likely as Fire is her CF) combined with Spleen qi deficiency. The Wind–Cold was only present occasionally so need not be listed as a main treatment principle. Treating the Fire CF and the treatment principles to do with Heart syndromes could also be merged together. A patient often has syndromes that are on the same Organ as the CF and the practitioner can often find one or more points that can deal with both of these at the same time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree