Cartilage Injuries

Benjamin V. Stone

Caroline Park

Anil S. Ranawat

DEFINITION

Hip cartilage injuries are common and have been reported to be as high as 50% of all intra-articular hip pathology in a series of athletes.5

Focal cartilage defects in the hip present a challenge to the surgeon, although cartilage repair and joint preservation procedures have improved as methods of controlling progression to symptomatic arthritis. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) remains a viable option.

Treatment of hip cartilage injuries is especially important in young patients, a population in which THA should be avoided as long as possible due to lower THA survival rates.11

ANATOMY

The articular surfaces of the hip include the femoral head and acetabulum. The femoral head is deeply recessed in the acetabulum, making surgical access difficult.

The articular cartilage of the hip joint is thickest ventrolaterally and becomes thinner in a concentric gradient toward the fovea of the femoral head and the acetabular fossa.19

The hip joint is surrounded anteriorly by the capsular, iliofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments and posteriorly by the ischiofemoral ligament.

The labrum forms a C-shaped circumferential border around the acetabulum, attached to the transverse acetabular ligament posteriorly and anteriorly. It extends contact over the femoral head, maintains intra-articular negative pressure, and serves to augment and protect the articular cartilage.

PATHOGENESIS

Possible causes of chondral injury to the hip include trauma, femoroacetabular impingement, synovial disorders, instability, osteonecrosis, osteochondritis dissecans, osteoarthritis, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and rheumatoid arthritis.16

Acute traumatic cartilage injury to the femoral head or acetabulum in the young athlete is often caused by a lateral impact injury, with impact loading over the greater trochanter.18

Chondral injury is associated with labral pathology. McCarthy et al20 showed that 73% of patients with fraying or torn labrum had chondral damage.

Femoroacetabular impingement is one of the most common causes of hip chondral injury. Cam impingement leads to anterosuperior acetabular cartilage delamination without associated labral injury. Pincer impingement causes a contrecoup cartilage injury on the posteroinferior acetabulum with labral damage and ossification. Both pathologies commonly exist concurrently.4

NATURAL HISTORY

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The history and physical exam are used to determine whether the source of pain is intra-articular or extra-articular.

Patients display the C-sign to describe deep interior hip pain. Intra-articular injury typically does not present with pain on palpation.

There is no specific test for chondral injuries of the hip, although the flexion internal rotation (FIR), log roll test, and scour test are suggestive of intra-articular pathology.

The scour test: With the patient supine, the hip is rotated and knee fully flexed. Any clicking, catching, or other associated mechanical symptoms should be noted.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are the hallmark of assessing hip pathology, but their use is limited in detecting chondral defects.

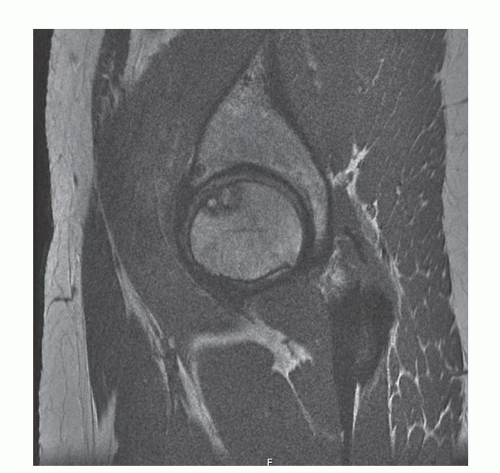

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard in detecting cartilage injuries of the hip (FIG 2).

Noncontrast, cartilage-specific MRI sequencing has been proven effective, with strong agreement to arthroscopic findings. Mintz et al21 demonstrated 92% and 86% agreement of MRI and arthroscopic findings for femoral articular cartilage defects in 92 patients with two readers. Acetabular cartilage defects showed 88% and 85% agreement between MRI and arthroscopic assessment.

Potter and Chong le26 also described the effectiveness of cartilage-specific MRI pulse sequences without contrast injection.

Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) may provide a more accurate assessment of chondral injury, with a contrast injection to outline the defect, although results have been less reliable than MRI. In addition, the contrast injection makes this a more invasive modality than MRI.

Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) enables assessment of glycosaminoglycan content and can thus detect deteriorating changes in cartilage. Cunningham et al8 showed that lower scores on the dGEMRIC index effectively predicted failure of periacetabular osteotomy.

Multidetector computed tomography arthrography (MDCTA) is another modality used to detect cartilage defects, but recent studies have shown conflicting levels of diagnostic accuracy.6,23,24

Ultrasound is a new option to diagnose hip injuries and can be used for diagnostic injections.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Non-hip

Referred pain from lower back, sacroiliac joint, abdominal wall, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract

FIG 2 • Sagittal MRI using coronal inversion recovery and fast spin echo axial sequences showing an osteochondral lesion in the weight-bearing portion of the right femoral head.

Hip

Extra-articular

Abductor, adductor, or rectus femoris tear

Piriformis syndrome

Hamstring syndrome

Trochanteric bursitis

Athletic pubalgia/osteitis pubis

Snapping from the iliopsoas or iliotibial band

Intra-articular

Labral tear

Avascular necrosis

Loose bodies

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The first line of nonoperative treatment for cartilage injuries includes rest, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and intra-articular injections. Surgical treatment is indicated if hip pain persists.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

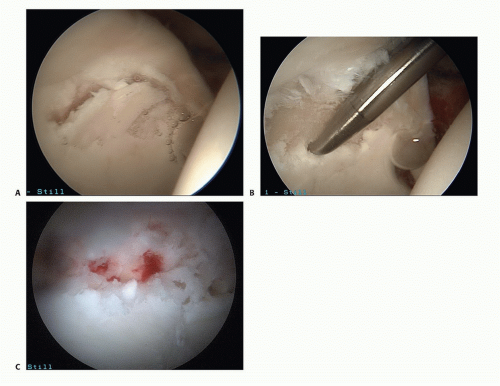

There exist five surgical treatment options for cartilage injuries of the hip. These include débridement, direct suture repair, microfracture, osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and autologous chondrocyte implantation or matrixinduced autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI/MACI).

OATS and ACI are more commonly done as open procedures, whereas débridement, repair, and microfracture are conducted arthroscopically.

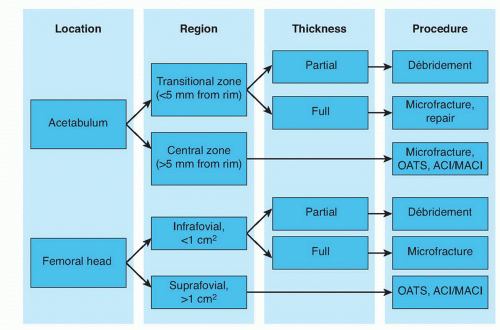

FIG 3 • Flowchart showing how the surgical procedure is chosen based on location and depth of defect as well as the surgeon’s experience with arthroscopic or open techniques.

The surgical treatment of choice depends on patient age, acuity of injury, location and depth of defect, and surgeon’s experience with arthroscopic or open techniques (FIG 3).

Injuries in non-weight-bearing regions are indicated for débridement or microfracture for larger, full-thickness defects.

Direct cartilage repair is emerging as an alternative to microfracture for transitional zone full-thickness delaminations of the acetabulum.

Cartilage injuries in weight-bearing regions of the hip, such as the suprafovial femoral head or central acetabulum, are treated with microfracture, OATS, or ACI/MACI. Some authors30 have suggested that microfracture is associated with inferior outcomes for defects larger than 400 mm2.

Contraindications for any of the cartilage procedures include unwillingness or inability to complete the rehabilitation protocol as well as kissing lesions, advanced arthritis, and infection.

Preoperative Planning

Plain radiographs are obtained to detect bony abnormalities, such as femoroacetabular impingement or acetabular dysplasia.

MRI/MRA is obtained to detect any associated soft tissue pathologies.

Ultrasound-guided injections may be done to confirm intraarticular injuries.

For both arthroscopic and open procedures, the entire hip joint is inspected and any labral pathology is addressed and treated as well as any loose bodies removed from the joint space.

Arthroscopically, the anterolateral portal is used to evaluate the anterior labrum, acetabular fossa, ligamentum teres, and fovea capitis.

Two normal variants of the acetabular fossa may appear similar to cartilage defects: the stellate crease, located superiorly, and the physeal scar, which can be anterior or posterior.

The arthroscope is then moved to the anterior portal to inspect the posterior aspects of the hip joint and the posterior recess.

Positioning

Arthroscopic procedures can be performed with the patient in either the supine or lateral position and can use two or three portals depending on the size and location of injury. Anterolateral and midanterior portals are used, occasionally with a posterolateral portal (FIG 4).

Arthroscopic procedures should use a fracture table with a well-padded perineal post to prevent injury to the pudendal nerve. A foot stirrup should be used to place 25 to 50 pounds of traction on the limb with the goal of 7 to 15 mm of joint distraction, as confirmed by the C-arm.

Open procedures use the surgical hip dislocation, with the patient in the lateral position, using a trochanteric flip osteotomy.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree