19

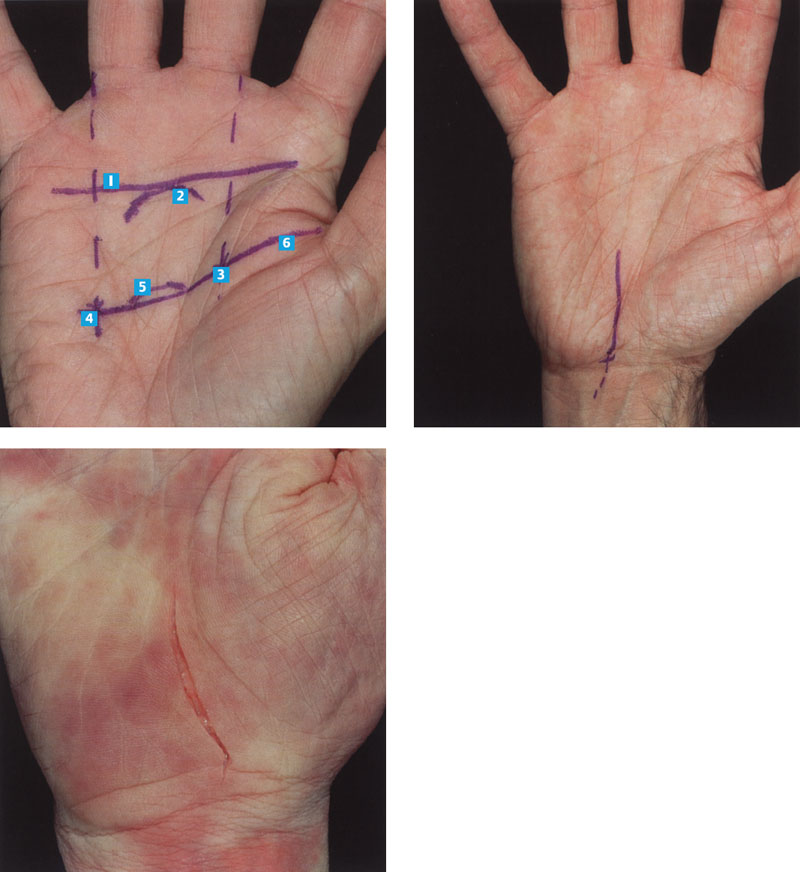

CARPAL TUNNEL APPROACH

USES

This approach is used for open carpal tunnel releases. It is also used to treat fracture of the hook of the hamate. It is further used as an extension of the forearm approaches to the volar aspect of the distal radius and volar aspect of the wrist such as might be needed in distal radius fractures or wrist dislocations.

ADVANTAGES

The approach is through the internervous area between the median and ulnar nerves. There are no vascular structures at risk if done correctly, and the incision heals well with little scarring. This approach is easy to extend proximally or distally as needed.

DISADVANTAGES

The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve supplies sensation to the base of the thenar area. It is a superficial structure that can be injured in this approach. If injured, it can form a neuroma and cause disabling pain in the palm.

STRUCTURES AT RISK

The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve is the most commonly injured structure. It comes off of the median nerve either in the midline or on the radial side.

The major disaster with the carpal tunnel approach is if the patient has a congenital abnormality of the motor branch to the thenar muscles that is not recognized, resulting in the branch being cut. This injury used to be called the million-dollar injury because of the size of the malpractice awards to compensate for the disability that results when the thenar muscles no longer function. Typically, the motor branch of the thenar muscles comes off the median nerve along the radial side just distal to the transverse carpal ligament and is, for the most part, out of the way if you are staying along the ulnar side of the canal. There are, however, multiple congenital abnormalities of this nerve that have been described and that put the branch at greater risk. Anything that is encountered coming through the transverse carpal ligament from its deep side should be very carefully dissected. There are typically no structures that penetrate the transverse carpal ligament.

If the dissection is carried too far distally, the superficial palmar arch is at risk. It is avoided by identifying the distal end of the transverse fibers, releasing them, and not doing any further cutting distally. Spreading of the soft tissues to identify the superficial palmar arch coming off of the ulnar artery is acceptable.

TECHNIQUE

The incision typically parallels the thenar flexor crease, approximately 2 mm to its ulnar side. Once the subcutaneous tissue is split, the palmar fascia is identified, cutting only transverse fibers. The flexor retinaculum should be split proximally for a distance of several centimeters, because occasionally it can be part of the impingement causing the carpal tunnel syndrome. Once the transverse carpal ligament is split, the median nerve can be visualized.

TRICKS

The major trick is to avoid all of the potential traps. The major way of avoiding damage to the median nerve is to stay along the ulnar side of the carpal canal when going through the transverse carpal ligament. Stay just radial to the hook of the hamate, which is usually easily palpable with a hemostat placed underneath the transverse carpal ligament in the carpal canal. You can then cut right down on the hemostat.

The trick to avoiding the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve is to stay to the ulnar side of the nerve.

The major trick to avoiding the superficial palmar arch is to identify the distal fibers of the transverse carpal ligament and not go distal to that with any dissection.

HOW TO TELL IF YOU ARE LOST

Once you have cut the flexor retinaculum proximal to the wrist, you should palpate the transverse carpal ligament with a hemostat or other similar blunt instrument and feel the grittiness of the transverse fibers. You should also feel the hook of the hamate from inside the carpal canal and then start your transection with the nerve protected. Once you are deep to the superficial fat and the palmar fascia, any further fat that is encountered distally indicates you are already distal to the end of the ligament and are putting the superficial palmar arch at great risk.

If the hook of the hamate is not just to the ulnar side of your transection, you are lost too far medially.

If you do not see multiple tendons once you go through the fascia, you have gone to the ulnar side of the hook of the hamate and are actually opening Guyon’s canal. Proximally there is no risk of getting lost.