The relevance of cancer rehabilitation as a public health issue grows steadily as cancer incidence, survival, and mean patient age increase. Reported rates of physical impairment and disability are already high, prior to the anticipated influx of aged cancer survivors. Despite the high prevalence of cancer-related disablement, treatment rates, even for readily remediable physical impairments, are as low as 1–2%. In addition to low referral rates, a challenge to patient-centric cancer rehabilitation is a fractured system that requires multiple visits to a range of specialists to address even a single issue, and cancer survivors generally have several. Effective solutions must acknowledge the limited cancer rehabilitation clinical work force and its clustering in tertiary centers, as well as the lack of consensus regarding the essential and effective components of a cancer rehabilitation program. A number of models of cancer rehabilitation service delivery have been developed, but, as yet, none have been empirically validated. This paper describes these models and proposes a taxonomy for stratifying the needs of cancer survivors. Modalities used to preserve or restore function among survivors range from simple, relatively intuitive activities to complex, integrated programs that include diagnostic and multi-modal pharmacological, manual, and even procedural interventions. Criteria for determining a survivor’s needs across this spectrum are proposed, and the role of the physiatrist as a vital advocate and champion discussed.

Key points

- •

Reported rates of cancer-related physical impairment and disability are currently high and expected to increase, but treatment rates, even for readily remediable physical impairments, remain as low as 1% to 2%.

- •

A limited clinical workforce has cancer rehabilitation training and these individuals are largely clustered in tertiary centers giving rise to access barriers.

- •

There is a need to clarify the scope of cancer rehabilitation by identifying its critical and effective components so that these can be made available to all survivors across diverse care settings.

- •

Currently, no accreditation, reimbursement, or designation criteria require institutions to provide high-quality cancer rehabilitation services.

- •

Models of cancer rehabilitation service delivery have been developed, but, as yet, none has been empirically validated.

Scope of the issue

The relevance of cancer rehabilitation as a public health issue grows steadily as cancer incidence, survival, and mean patient age increase.

Epidemiology

Per latest estimates, 15.5 million cancer survivors currently reside in the United States. This figure includes patients presumed cured and those with active disease. In less than 10 years, the US prevalence of cancer survivorship, similarly defined, will approach 20 million, and current estimates do not account for increased responsiveness achieved with biological agents, precision medicine, and the expansion of screening programs. The advancing age of the US population will contribute not only to increased prevalence but also to an increased burden of disability among cancer survivors. Older cancer survivors have increased rates of multimorbidity, premorbid disablement, and cancer treatment–related toxicity. It is expected that by 2020 approximately three-quarters of cancer survivors will be age 65 or older.

Reported rates of physical impairment and disability are already high, prior to the anticipated influx of aged cancer survivors. Efforts to systematically describe rates of physical impairments have highlighted differences across survivorship populations. For example, 20% of childhood compared with 53% of adult-onset cancer survivors report limitations in their functioning, and as many as two-thirds of breast cancer survivors experience 1 or more long-term adverse sequelae (eg, fatigue, lymphedema, pain, and contractures). As expected, rates of physical impairment increase among patients with metastatic cancer. In a cohort of 163 patients receiving treatment of stage IV breast cancer, 92% endorsed at least 1 physical impairment, and the mean number of impairments per patient was 3.3. The presence of physical impairments reduces quality-of-life (QOL) and participation in work, family, and society. Additionally, the presence of impairments and related disability radically increase health care utilization.

Despite the high prevalence of cancer-related disablement, treatment rates, even for readily remediable physical impairments, are as low as 1% to 2%. The reasons for the decades-long persistence of undertreatment are complex and multifold. Low detection, documentation, and referral rates in oncology practices are an important factor. Systemic issues, however, for example, shortages of oncologists and primary care practitioners, that constrain attention directed beyond cancer treatment, also contribute. The United States increasingly struggles to meet the complex and varied needs of its rapidly expanding cancer survivor population. Advocates have proposed both de facto operationalized and novel models for cancer rehabilitation that range from a discrete focus on singular impairments to a more holistic scope that encompasses survivors’ physical, psychological, vocational, and social capabilities.

A challenge to integrated, comprehensive and patient-centric cancer rehabilitation is the currently fractured system that requires multiple visits to a range of specialists spanning different disciplines to address even a single issue, and cancer survivors generally have several. A similar challenge has been highlighted by Bruera and Hui in palliative care. Cancer survivors, irrespective of their disease or treatment status, have limited fiscal and energetic resources. Their support systems are often overtaxed and frayed. Even were there an adequately trained and geographically dispersed clinical workforce, the travel, temporal, and monetary demands of current fee-for-service care delivery structures would pose formidable access barriers. Although the raw ingredients for a reconceptualization of medical practice and reimbursement are present in the Affordable Care Act, it may take decades to have a meaningful impact on the legacy of fee-for-service reimbursement on the delivery of multidisciplinary supportive care. This situation highlights the vital need to meet as many needs as possible with a 1-stop shop, near-term solution. Physiatrists with their diagnostic, prescriptive, educational, and advocacy capabilities are poised to play a vital role.

This article proposes a skeletal taxonomy for stratifying the needs of cancer survivors, examines models of cancer rehabilitation that are de facto operational and others that remain largely theoretic, and highlights important considerations in developing pragmatic, near-term solutions to cancer survivors’ pressing need for function-directed care.

Needed First Steps

Any effective solution to the challenge of meeting cancer survivors’ disparate rehabilitation needs must acknowledge the alarmingly limited clinical workforce with cancer rehabilitation training and that such clinicians are largely clustered in tertiary centers where fewer than 15% of patients receive their cancer care. In addition to training more providers in cancer rehabilitation, the provider shortage underscores the need to explore strategies that neutralize personnel and geographic barriers. Legislative, infrastructural, and technological support for telemedicine has increased, and trials are currently under way to determine the comparative effectiveness of tele-rehabilitation for cancer-related symptoms and disablement. A complementary approach to extending the reach of limited cancer rehabilitation specialists is the empowerment and support of nonspecialist clinicians to detect and treat threats to survivors’ functionality. Guidelines, print materials, and Web-based resources for the management of even common cancer-related impairments are, however, currently limited. As discussed later, survivors find travel and copayments burdensome. It may, therefore, be most patient-centric to address their primary rehabilitation issues through the local providers that address their primary and cancer-directed care and restrict physiatric consultations for problems that have not responded to first-line therapy or occur in complex and morbid individuals. For this to occur, however, it is essential that physiatrists and specialty-trained cancer therapists work to enable primary providers and oncological care teams, which should include varied types of highly qualified allied health professionals to provide first-line rehabilitative interventions.

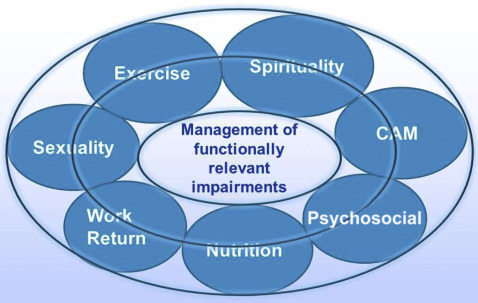

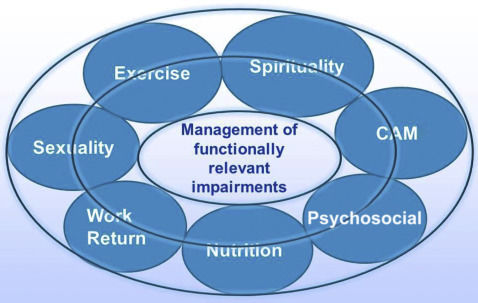

If cancer rehabilitation is to advance, there is also a critical need to forge consensus regarding its scope. No one argues that cancer survivors have staggeringly complex needs spanning physical, vocational, and sexual domains, to name a few. A majority of survivors endorse 1 or more of the following: fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, pain, neuropathies, balance problems, mobility issues, lymphedema, bladder and bowel problems, stoma care, dysphonia and other communication difficulties, dysphagia, and psychosocial problems. This heterogeneity is compounded by treatments of these issues that may require diverse modalities, including conventional allopathic and alternative treatments. Fig. 1 displays potential components of a comprehensive cancer rehabilitation program —in addition to the generally accepted medical management of impairments and comorbidities that degrade function — suggested during a summit held at the National Institutes of Health in 2015 and recently described in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation . The scope in Fig. 1 reflects the diverse disciplines and therapeutic approaches currently allied to cancer rehabilitation. An alarming corollary of this breadth, because a minority of survivors currently receive even rudimentary cancer rehabilitation, is that services can only reliably and democratically be provided that fall within an aggressively constrained scope. Therefore, an initial minimalist approach emphasizing access over breadth seems reasonable. Rigorous constraint need not be fixed and should evolve over time as capacity increases. At present, however, identifying survivors’ most pressing and prevalent needs, determining which evidence-based treatments effectively mitigate them, and establishing a conservative but doable structure for delivering these treatments, are logical first steps.

Uncertainty regarding the roles of different disciplines in providing cancer rehabilitation services is, in part, a consequence of scope ambiguity. In addition to physiatrists, physical, occupational, recreational, and speech therapists; athletic trainers; exercise physiologists; and nurses routinely provide function-oriented care. Some oncological clinicians also extend their practices to encompass dimensions of care, such as lymphedema and fatigue management. National efforts from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Cancer Society are beginning in 2016 to better coordinate and deliver care for people with cancer. In the past, however, limited consensus has been forged regarding disciplinary roles in cancer rehabilitation and needed patterns of interdisciplinary referrals and interface. As a result, idiosyncratic and institution-specific patterns of care delivery have developed. These generally reflect clinician skills and interest, and institutional emphases, for example, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. This diversity of delivery patterns reinforces role ambiguity and sustains a lack of clarity regarding the essential components of a cancer rehabilitation program. For example, the MD Anderson Cancer Center rehabilitation program focuses on its imbedded inpatient acute rehabilitation facility, whereas the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s is more outpatient directed. Although institutional differences are inevitable and often positive, emerging organically from unique institutional strengths to meet the needs of specific populations, they have had the unfortunate effect of perpetuating cancer rehabilitation’s nebulous components and boundaries. Consequently, oncological trainees, for example, medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists, have not had the opportunity to learn practice patterns that integrate rehabilitation services in a manner that generalizes across care settings.

Because many cancer rehabilitation interventions are nonurgent and negotiated, patient preferences play a central role. Several findings warrant mention. First, whereas a majority of cancer survivors do not discuss exercise or their functionality with either their primary or oncological care teams, they prefer that oncologists initiate discussions about exercise and make appropriate referrals. This preference has been noted across different institutions and survivor populations. Second, survivors desire the continuous delivery of exercise-related information, particularly as it relates to their cancer, beginning early in the course of their treatment with appropriate adaptation as they complete or change treatments and, ultimately, as some enter long-term disease-free survivorship. Third, up to two-thirds of patients with late-stage cancer express ambivalence or disinterest in receiving rehabilitation services despite high rates of disability and related distress. Last, some cancer survivors have limited understanding of the dose, type, and frequency of exercise required to achieve symptom relief and functional improvement, with many maintaining that their usual daily activities offer sufficient rigor. These issues highlight the critical importance of educational initiatives targeting patients and providers to screen for impairments that may make independent exercise unsafe without rehabilitation interventions and to clarify the benefits of integrating activity enhancement and rehabilitative service provision in conventional cancer care.

What Stakeholders Say — Mixed Messages

The number of large-scale, high profile, cancer-related organizations, both federal and private, that endorse the importance of cancer rehabilitation is simultaneously reassuring and disheartening, the latter because although over the last decade, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Society of Clinical Oncology, and American Cancer Society have all increasingly emphasized the functional needs of survivors, no accreditation, reimbursement, or designation criteria require institutions to provide high-quality cancer rehabilitation services. Strikingly, the NCI’s mission statement states that it “…coordinates the National Cancer Program, which conducts and supports … rehabilitation from cancer…” Yet, the NCI does not require or recommend that its comprehensive cancer centers provide their patients with rehabilitation services.

There are several important exceptions to this general trend. First, the American College of Surgeons stands out with its Commission on Cancer mandating that, for cancer center accreditation, institutions must ensure the availability of rehabilitation services. Although this is laudable and the only such mandate, it does not go far enough because it does not require on-site or coordinated delivery of cancer rehabilitation services as a standard part of cancer care. Second, in 2014, the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities International (CARF) introduced accreditation standards for cancer rehabilitation specialty programs. This specialty accreditation can be applied to hospitals, health care systems, outpatient clinics, and community-based programs. Although availability of the new CARF accreditation may not incentivize institutions, it represents a vital first step as a formal effort to enumerate the essential components of a cancer rehabilitation program. Three provider certification programs have also been developed. The Survivorship Training and Rehabilitation program, a commercial entity, offers therapist training that may lead to institutional Survivorship Training and Rehabilitation certification. The American College of Sports Medicine developed a certifying examination for cancer exercise trainers. The American Physical Therapy Association recently developed oncology certification for physical therapists, although administration of the first certification examination is not anticipated until Spring 2019. As yet, the outcome and utilization implications of practitioner or institutional certification are not known.

Scope of the issue

The relevance of cancer rehabilitation as a public health issue grows steadily as cancer incidence, survival, and mean patient age increase.

Epidemiology

Per latest estimates, 15.5 million cancer survivors currently reside in the United States. This figure includes patients presumed cured and those with active disease. In less than 10 years, the US prevalence of cancer survivorship, similarly defined, will approach 20 million, and current estimates do not account for increased responsiveness achieved with biological agents, precision medicine, and the expansion of screening programs. The advancing age of the US population will contribute not only to increased prevalence but also to an increased burden of disability among cancer survivors. Older cancer survivors have increased rates of multimorbidity, premorbid disablement, and cancer treatment–related toxicity. It is expected that by 2020 approximately three-quarters of cancer survivors will be age 65 or older.

Reported rates of physical impairment and disability are already high, prior to the anticipated influx of aged cancer survivors. Efforts to systematically describe rates of physical impairments have highlighted differences across survivorship populations. For example, 20% of childhood compared with 53% of adult-onset cancer survivors report limitations in their functioning, and as many as two-thirds of breast cancer survivors experience 1 or more long-term adverse sequelae (eg, fatigue, lymphedema, pain, and contractures). As expected, rates of physical impairment increase among patients with metastatic cancer. In a cohort of 163 patients receiving treatment of stage IV breast cancer, 92% endorsed at least 1 physical impairment, and the mean number of impairments per patient was 3.3. The presence of physical impairments reduces quality-of-life (QOL) and participation in work, family, and society. Additionally, the presence of impairments and related disability radically increase health care utilization.

Despite the high prevalence of cancer-related disablement, treatment rates, even for readily remediable physical impairments, are as low as 1% to 2%. The reasons for the decades-long persistence of undertreatment are complex and multifold. Low detection, documentation, and referral rates in oncology practices are an important factor. Systemic issues, however, for example, shortages of oncologists and primary care practitioners, that constrain attention directed beyond cancer treatment, also contribute. The United States increasingly struggles to meet the complex and varied needs of its rapidly expanding cancer survivor population. Advocates have proposed both de facto operationalized and novel models for cancer rehabilitation that range from a discrete focus on singular impairments to a more holistic scope that encompasses survivors’ physical, psychological, vocational, and social capabilities.

A challenge to integrated, comprehensive and patient-centric cancer rehabilitation is the currently fractured system that requires multiple visits to a range of specialists spanning different disciplines to address even a single issue, and cancer survivors generally have several. A similar challenge has been highlighted by Bruera and Hui in palliative care. Cancer survivors, irrespective of their disease or treatment status, have limited fiscal and energetic resources. Their support systems are often overtaxed and frayed. Even were there an adequately trained and geographically dispersed clinical workforce, the travel, temporal, and monetary demands of current fee-for-service care delivery structures would pose formidable access barriers. Although the raw ingredients for a reconceptualization of medical practice and reimbursement are present in the Affordable Care Act, it may take decades to have a meaningful impact on the legacy of fee-for-service reimbursement on the delivery of multidisciplinary supportive care. This situation highlights the vital need to meet as many needs as possible with a 1-stop shop, near-term solution. Physiatrists with their diagnostic, prescriptive, educational, and advocacy capabilities are poised to play a vital role.

This article proposes a skeletal taxonomy for stratifying the needs of cancer survivors, examines models of cancer rehabilitation that are de facto operational and others that remain largely theoretic, and highlights important considerations in developing pragmatic, near-term solutions to cancer survivors’ pressing need for function-directed care.

Needed First Steps

Any effective solution to the challenge of meeting cancer survivors’ disparate rehabilitation needs must acknowledge the alarmingly limited clinical workforce with cancer rehabilitation training and that such clinicians are largely clustered in tertiary centers where fewer than 15% of patients receive their cancer care. In addition to training more providers in cancer rehabilitation, the provider shortage underscores the need to explore strategies that neutralize personnel and geographic barriers. Legislative, infrastructural, and technological support for telemedicine has increased, and trials are currently under way to determine the comparative effectiveness of tele-rehabilitation for cancer-related symptoms and disablement. A complementary approach to extending the reach of limited cancer rehabilitation specialists is the empowerment and support of nonspecialist clinicians to detect and treat threats to survivors’ functionality. Guidelines, print materials, and Web-based resources for the management of even common cancer-related impairments are, however, currently limited. As discussed later, survivors find travel and copayments burdensome. It may, therefore, be most patient-centric to address their primary rehabilitation issues through the local providers that address their primary and cancer-directed care and restrict physiatric consultations for problems that have not responded to first-line therapy or occur in complex and morbid individuals. For this to occur, however, it is essential that physiatrists and specialty-trained cancer therapists work to enable primary providers and oncological care teams, which should include varied types of highly qualified allied health professionals to provide first-line rehabilitative interventions.

If cancer rehabilitation is to advance, there is also a critical need to forge consensus regarding its scope. No one argues that cancer survivors have staggeringly complex needs spanning physical, vocational, and sexual domains, to name a few. A majority of survivors endorse 1 or more of the following: fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, pain, neuropathies, balance problems, mobility issues, lymphedema, bladder and bowel problems, stoma care, dysphonia and other communication difficulties, dysphagia, and psychosocial problems. This heterogeneity is compounded by treatments of these issues that may require diverse modalities, including conventional allopathic and alternative treatments. Fig. 1 displays potential components of a comprehensive cancer rehabilitation program —in addition to the generally accepted medical management of impairments and comorbidities that degrade function — suggested during a summit held at the National Institutes of Health in 2015 and recently described in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation . The scope in Fig. 1 reflects the diverse disciplines and therapeutic approaches currently allied to cancer rehabilitation. An alarming corollary of this breadth, because a minority of survivors currently receive even rudimentary cancer rehabilitation, is that services can only reliably and democratically be provided that fall within an aggressively constrained scope. Therefore, an initial minimalist approach emphasizing access over breadth seems reasonable. Rigorous constraint need not be fixed and should evolve over time as capacity increases. At present, however, identifying survivors’ most pressing and prevalent needs, determining which evidence-based treatments effectively mitigate them, and establishing a conservative but doable structure for delivering these treatments, are logical first steps.

Uncertainty regarding the roles of different disciplines in providing cancer rehabilitation services is, in part, a consequence of scope ambiguity. In addition to physiatrists, physical, occupational, recreational, and speech therapists; athletic trainers; exercise physiologists; and nurses routinely provide function-oriented care. Some oncological clinicians also extend their practices to encompass dimensions of care, such as lymphedema and fatigue management. National efforts from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Cancer Society are beginning in 2016 to better coordinate and deliver care for people with cancer. In the past, however, limited consensus has been forged regarding disciplinary roles in cancer rehabilitation and needed patterns of interdisciplinary referrals and interface. As a result, idiosyncratic and institution-specific patterns of care delivery have developed. These generally reflect clinician skills and interest, and institutional emphases, for example, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. This diversity of delivery patterns reinforces role ambiguity and sustains a lack of clarity regarding the essential components of a cancer rehabilitation program. For example, the MD Anderson Cancer Center rehabilitation program focuses on its imbedded inpatient acute rehabilitation facility, whereas the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s is more outpatient directed. Although institutional differences are inevitable and often positive, emerging organically from unique institutional strengths to meet the needs of specific populations, they have had the unfortunate effect of perpetuating cancer rehabilitation’s nebulous components and boundaries. Consequently, oncological trainees, for example, medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists, have not had the opportunity to learn practice patterns that integrate rehabilitation services in a manner that generalizes across care settings.

Because many cancer rehabilitation interventions are nonurgent and negotiated, patient preferences play a central role. Several findings warrant mention. First, whereas a majority of cancer survivors do not discuss exercise or their functionality with either their primary or oncological care teams, they prefer that oncologists initiate discussions about exercise and make appropriate referrals. This preference has been noted across different institutions and survivor populations. Second, survivors desire the continuous delivery of exercise-related information, particularly as it relates to their cancer, beginning early in the course of their treatment with appropriate adaptation as they complete or change treatments and, ultimately, as some enter long-term disease-free survivorship. Third, up to two-thirds of patients with late-stage cancer express ambivalence or disinterest in receiving rehabilitation services despite high rates of disability and related distress. Last, some cancer survivors have limited understanding of the dose, type, and frequency of exercise required to achieve symptom relief and functional improvement, with many maintaining that their usual daily activities offer sufficient rigor. These issues highlight the critical importance of educational initiatives targeting patients and providers to screen for impairments that may make independent exercise unsafe without rehabilitation interventions and to clarify the benefits of integrating activity enhancement and rehabilitative service provision in conventional cancer care.

What Stakeholders Say — Mixed Messages

The number of large-scale, high profile, cancer-related organizations, both federal and private, that endorse the importance of cancer rehabilitation is simultaneously reassuring and disheartening, the latter because although over the last decade, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Society of Clinical Oncology, and American Cancer Society have all increasingly emphasized the functional needs of survivors, no accreditation, reimbursement, or designation criteria require institutions to provide high-quality cancer rehabilitation services. Strikingly, the NCI’s mission statement states that it “…coordinates the National Cancer Program, which conducts and supports … rehabilitation from cancer…” Yet, the NCI does not require or recommend that its comprehensive cancer centers provide their patients with rehabilitation services.

There are several important exceptions to this general trend. First, the American College of Surgeons stands out with its Commission on Cancer mandating that, for cancer center accreditation, institutions must ensure the availability of rehabilitation services. Although this is laudable and the only such mandate, it does not go far enough because it does not require on-site or coordinated delivery of cancer rehabilitation services as a standard part of cancer care. Second, in 2014, the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities International (CARF) introduced accreditation standards for cancer rehabilitation specialty programs. This specialty accreditation can be applied to hospitals, health care systems, outpatient clinics, and community-based programs. Although availability of the new CARF accreditation may not incentivize institutions, it represents a vital first step as a formal effort to enumerate the essential components of a cancer rehabilitation program. Three provider certification programs have also been developed. The Survivorship Training and Rehabilitation program, a commercial entity, offers therapist training that may lead to institutional Survivorship Training and Rehabilitation certification. The American College of Sports Medicine developed a certifying examination for cancer exercise trainers. The American Physical Therapy Association recently developed oncology certification for physical therapists, although administration of the first certification examination is not anticipated until Spring 2019. As yet, the outcome and utilization implications of practitioner or institutional certification are not known.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree