Chapter 38

Breast Mass (Case 30)

Tamara Donatelli DO, Jennifer Sabol MD, Roxane Weighall DO, Ari D. Brooks MD, and Mary Denshaw-Burke MD

Case: Breast mass in a 44-year-old female.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign | Malignant |

Fibroadenoma | Infiltrating (or invasive) ductal carcinoma |

Cyst | Invasive lobular carcinoma |

Benign breast nodularity |

Speaking Intelligently

When evaluating a breast mass, we always think about the triple test (clinical examination, imaging, pathology). We examine the patient while paying attention to the characteristics of the mass and review the mammogram or ultrasonogram to determine our level of clinical suspicion. If our level of suspicion warrants a tissue diagnosis, we use the least invasive biopsy technique that will yield an accurate diagnosis. In the case of a palpable breast mass, this is most often a fine-needle aspiration biopsy or a core needle biopsy. Although we may occasionally suspect that the mass represents benign breast nodularity, biopsy is still recommended for peace of mind (sometimes ours, often the patient’s).

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Any palpable mass should be imaged. In a 44-year-old female, diagnostic mammography, including ultrasonography, is indicated for complete evaluation.

History

Physical Examination

• Be sure to discuss your findings with the patient.

Table 38-1 Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) | |

Category | Recommendation |

0: Incomplete: Need Additional Imaging Evaluation and/or Prior Mammograms | More information is needed to determine whether a finding is abnormal |

1: Negative | Continue routine screening |

2: Benign | Continue routine screening |

3: Probably Benign | Initial short-interval follow-up suggested (usually 6 months) |

4: Suspicious Abnormality | Usually requires biopsy |

5: Highly Suggestive of Malignancy | Appropriate actions should be taken (requires biopsy or surgical treatment) |

6: Known Biopsy-Proven Malignancy | Appropriate actions should taken |

From the American College of Radiology (ACR). ACR BI-RADS®–4th Edition. ACR Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, Breast Imaging Atlas; BI-RADS. Reston, VA. American College of Radiology; 2003. Reprinted as modified and approved with permission of the American College of Radiology. No other representation of this material is authorized without expressed, written permission from the American College of Radiology. | |

Common Mammographic Findings

Assessment of risk depends on characteristics of findings and time frame of development.

Masses

Benign Mammographic Masses

Well-circumscribed and smooth masses are suggestive of a benign etiology. The typical benign mass is either a cyst or a fibroadenoma. Ultrasonography will differentiate the two.

Malignant Mammographic Masses

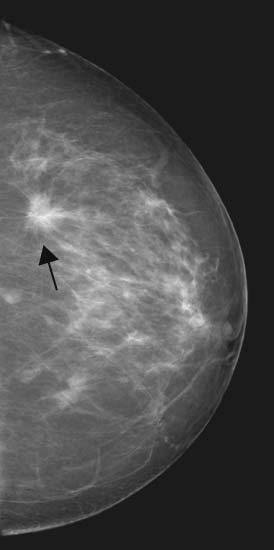

See Figure 38-1.

Figure 38-1 Malignant masses. Typically irregular and spiculated, and often contain calcifications. (From Mann B. Surgery: a competency-based companion. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Figure 20-4.)

Architectural Distortion

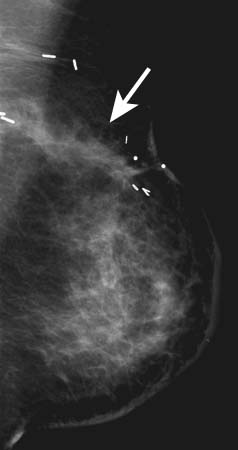

See Figure 38-2.

Figure 38-2 Architectural distortion. May be the earliest sign of breast cancer. May also be associated with scars from previous surgery. (From Mann B: Surgery: a competency-based companion. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Figure 20-5.)

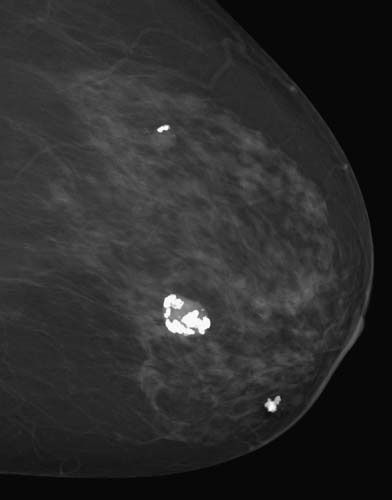

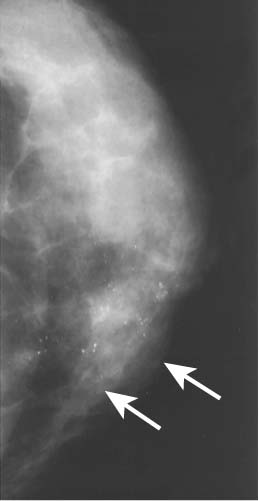

Calcifications

Calcifications are the deposition of calcium in the breast tissue or its elements. Calcifications are divided into three types: benign, indeterminate, and high probability of malignancy (Figs. 38-3 and 38-4).

Figure 38-3 Benign calcifications can be coarse, rodlike associated with blood vessels, round, popcorn-shaped, or milk of calcium (concave). (From Mann B: Surgery: a competency-based companion. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Figure 20-1.)

Figure 38-4 Malignant calcifications are more likely to be pleomorphic, heterogeneous, clustered, or branching. (From Mann B: Surgery: a competency-based companion. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Figure 20-2.)

PATIENT CARE

Biopsy Approaches

$320 | |

$320 | |

$570 | |

$1784 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

Fibroadenoma | |

Pφ | Fibroadenomas are well-circumscribed, solid masses. They contain fibrous and epithelial elements, and are thought to represent benign hyperplastic lobules. The cut surface is white or yellow, and bulging beyond its pseudocapsule. |

TP | Fibroadenomas can appear at any age. The typical patient is younger than 40 years; fibroadenomas are common in teenagers. Physical exam demonstrates a smooth, well-circumscribed mass that is mobile and rubbery in texture. |

Dx | Ultrasound shows a mass with smooth margins and benign characteristics. In older women, “popcorn calcifications” may be associated with involuting fibroadenomas. Core needle biopsy can confirm the diagnosis. |

Small asymptomatic fibroadenomas do not have to be excised. However, excision is recommended if there is evidence of growth, an inconclusive needle biopsy, size > 2–3 cm, or bothersome tenderness. See Cecil Essentials 71. | |

Cyst | |

Pφ | Cysts are round to oval well-circumscribed masses that can be single or multiple. They are fluid-filled benign sacs located within the fibrous tissue of the breast. |

TP | Cysts are common in patients undergoing hormonal fluctuations. They are common in premenopausal women and around the onset of menopause. On examination, cysts are smooth and frequently tender. |

Dx | On mammogram, cysts have a smooth distinct border. An ultrasound will easily confirm the presence of fluid and has a diagnostic accuracy of close to 100%. Cysts may fluctuate in size or presence over serial examinations. |

Tx | Asymptomatic cysts do not require treatment. Those that are painful or of concern (having septations, intracystic growth, or thick walls) should be aspirated or excised depending on how suspicious they appear. Cyst fluid is typically “straw-colored.” Other typical benign fluid colors are white, gray, blue, and green. Bloody aspirate should always be sent for cytology and the patient reevaluated by imaging with the possibility of excisional biopsy in mind. See Cecil Essentials 71. |

Benign Breast Nodularity | |

Pφ | Normal breast tissue can have a nodular pattern in some women. This is more marked in the upper outer quadrants and is often very tender in response to normal cyclic hormonal variations. This cyclic tenderness is more pronounced as women become perimenopausal, and often one breast is affected more than the other. |

TP | The typical patient is premenopausal and complains of an intermittently tender mass that seems to fluctuate in size. The pain is characteristically worse in the 7 days before her menstrual period and then begins to abate with the onset of menses. |

Mammograms and ultrasonography typically show normal breast tissue. Ultrasonography may show thickened breast tissue approaching the skin in the area of the mass. Women with dense breasts may require a breast MRI scan to rule out carcinoma. | |

Tx | If the palpable mass is believed to be suspicious or if a woman’s anxiety level is acute, a biopsy should be performed to exclude malignancy. See Cecil Essentials 71. |

Malignant Mass | |

Pφ | The common malignant breast masses are invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. |

TP | Infiltrating (or invasive) ductal carcinoma: The typical patient has a firm dominant mobile mass found by self-examination or by a health-care practitioner. The mass may be associated with skin retraction, palpable adenopathy, and/or nipple discharge. In the more advanced stages, the mass may be fixed to surrounding structures and associated with erythema, skin edema, skin ulceration, peau d’orange, and matted axillary nodes. A carcinoma may be nonpalpable and present as an unexpected density on the screening mammogram. Invasive lobular carcinoma represents only 5% to 10% of breast cancers and is classically more difficult to identify mammographically as well as on palpation because of its classic single-cell (Indian file) growth histologically. Lobular carcinoma is often perceived as a “thickening” rather than as a discrete mass, and what you feel or see may be only the “tip of the iceberg.” The final pathologic size of an invasive lobular cancer is often much greater than anticipated as a result of this growth pattern. |

Dx | Tissue biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis of a malignant mass. If the lesion is palpable, a fine-needle aspiration or percutaneous core needle biopsy can be performed in the office. (Many surgeons prefer to be sure a mammogram is obtained before biopsy because of the risk of hematoma formation.) Ultrasound or stereotactic guidance may be utilized for diagnosis if the lesion is not palpable. Open incisional or excisional biopsies are appropriate when needle biopsy cannot be performed or is inconclusive. |

Management of breast carcinoma: All patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer should receive a metastatic workup appropriate to clinical stage to rule out distant disease to the most common sites of metastasis, namely bone, lung, and liver. Fewer than 10% of patients will present at stage IV. Once patients appear to have locally resectable disease, the patients are confronted with two main issues: local control and microscopic systemic disease control. Local control is often the first decision a patient faces and can often be confusing. Try to simplify these choices, and describe the options of mastectomy and breast conservation to the patient. Mastectomy involves removing all of the breast tissue (simple mastectomy) or breast tissue and surrounding lymph nodes if involved (modified radical mastectomy), while preserving much of the overlying skin. It may or may not include immediate breast reconstruction. Breast conservation therapy consists of lumpectomy to negative margins (for unifocal disease) and radiation therapy (either whole or partial breast irradiation). It is important to note that these two local treatment choices for invasive carcinoma are equivalent in terms of overall survival. Local recurrence after mastectomy is 14%, while it is 5% to 7% following breast conservation. Some patients may not be considered good candidates for breast conservation therapy if they have multifocal disease, extensive skin involvement such as inflammatory cancer, or inability to complete radiation therapy. All patients having cancer, with the exception of those with noninvasive cancer, will have evaluation of their lymph nodes at the time of surgery to evaluate the extent of disease. Traditionally, if there is biopsy-proven lymph node involvement, additional surgical therapy has included resection of levels I and II axillary nodes or palpable disease. However, a recent study released by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z-11 Trial has suggested that additional axillary surgery may not be necessary and that the small amount of microscopic disease may be eradicated by chemotherapy. While this is not yet the standard of care, these data may lead to a paradigm shift in the surgical management of breast cancer. | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy plays a more significant role in patients who have a tumor that is ER/PR negative, HER2/neu positive, or with axillary lymph node involvement. In general, the patients with the greatest risk of disease recurrence obtain the largest absolute benefit from the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Multiple chemotherapy drug combinations are appropriate in the adjuvant setting, often including anthracyclines and taxanes. For patients with ER- or PR-positive cancers, oral anti-estrogen hormonal therapy for a minimum of 5 years reduces the risk of local and systemic recurrence as well as contralateral breast cancer by 40% to 50%. Premenopausal or perimenopausal women are treated with tamoxifen. Postmenopausal women may be treated with either tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors; however, aromatase inhibitors are considered the first-line therapy in postmenopausal women. Adjuvant! Online is a wonderful risk assessment tool that can help the clinician assess an individual’s risk of dying of comorbid disease versus risk of systemic disease recurrence, and estimates both the impact of anti-estrogen hormonal therapy as well as cytotoxic chemotherapy on overall survival. Once a patient’s systemic risk has been addressed, the final treatment step is radiation therapy if indicated. All patients undergoing breast conservation will require radiation as part of their treatment. Most patients undergoing mastectomy will require radiation only if the tumor size is ≥5 cm, if there are positive margins of resection, if there is extracapsular nodal involvement, or if there is involvement of four or more axillary lymph nodes with metastatic cancer. See Cecil Essentials 57, 59, 68. |