Bone defects represent a difficult problem for the clinician. They entail a sustained increase in hospitalization, risk of complications, and associated increase in expenses. This article discusses bone defects caused by high-energy injuries, bone loss, infected nonunions, and nonunions.

Bone defects represent a difficult problem for the clinician. They entail a sustained increase in hospitalization, risk of complications, and associated increase in expenses ( Fig. 1 ). The average cost for patients suffering from fractures following motor vehicle accidents has been estimated at US$10,000 per case. Nonunions cost about US$25,000; the estimate varies according to the location of the fracture site (humerus<tibia<femur). These direct costs apply only to nonunions that heal uneventfully after the first revision surgery. In contrast, bone loss imposes a longer period of treatment, and has an even higher complication rate and associated costs. To our knowledge, there is no published information on the costs incurred as a result of bone loss.

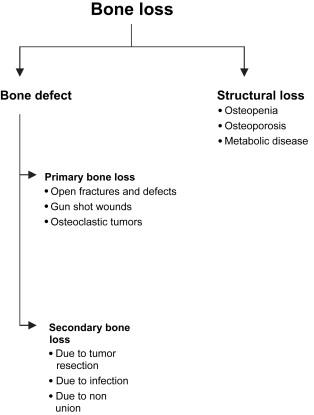

The term bone loss may refer either to structural defects and regions of missing bone caused by external factors or true defects and structural loss within existing bone, such as in osteopenia. Fig. 2 gives an overview of causes for bone loss.

By definition, primary and secondary bone loss can be differentiated. Primary bone loss may occur in bone diseases, such as malignancy. Secondary bone loss is most commonly caused by metastatic disease. Tumor metastases may have either osteoblastic or osteolytic features. Both damage the bone in terms of structure, nutrition, and metabolism. Trauma is the most common cause of bone defects ( Fig. 3 ).

In the planning of treatment for bone loss, several factors must be considered: the quality of the soft tissue envelope, the quality of vascular supply, and the presence or absence of an infection. In terms of treatment there is a wide variety of options.

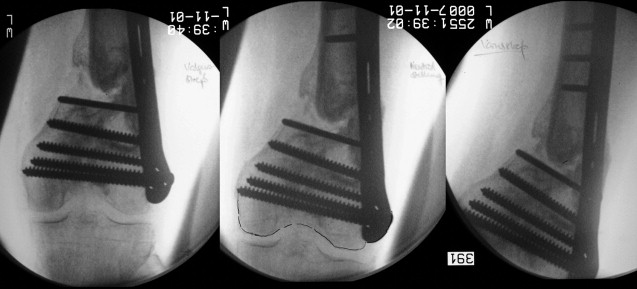

In the acute setting, shortening of the bone may be considered, as depicted in Fig. 4 . If shortening is considered, several concepts have to be considered. First, the bony ends should be adapted to allow the best contact possible. Second, the viability of the bone is of pivotal importance, thus requiring planned revision surgery. Third, coverage of all bony structures is crucial to avoid infection. In humeral and tibial defects this may be used if the distance between the fracture ends ranges up to 2 inches. In the femur, larger defects may be treated using this technique. According to isolated reports, defects of up to 3 inches have been treated by shortening. The advantage of acute shortening is that there is a greater chance of avoiding the necessity of free flap coverage by facilitating secondary definitive closure or early skin grafting. Disadvantages of this approach include shortening of the affected limb and prolonged treatment until the preinjury length is achieved.