Bilateral Simultaneous Total Knee Arthroplasty

Because arthritis of the knee has a significant incidence of bilaterality, both patients and surgeons often consider the possibility of bilateral simultaneous total knee arthroplasty (TKA). I am a strong advocate of this procedure in properly selected patients, and the incidence of performing bilateral knee replacements in my practice has varied from 10% to 20% of my knee replacement patients.

The Decision

For me to consider bilateral simultaneous knee replacement, both knees must have significant structural damage. It is best if the patient cannot decide which knee is more bothersome. In borderline cases, I ask the patient to pretend that the worse knee is normal. Then I ask if the patient would be seeing me for consideration of knee replacement on the other, less involved side. If the answer to this question is “yes,” I consider the patient a potential candidate for bilateral knee replacement. If the answer is “no,” I recommend operating only on the worse knee, and I expect that the operation on the second knee can be delayed for a considerable period.

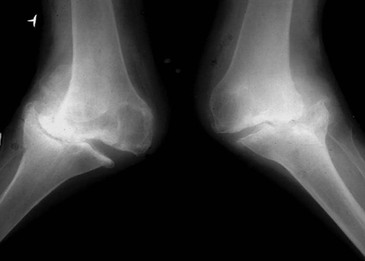

Strong indications for bilateral simultaneous TKA are bilateral severe angular deformity (Figure 12-1), bilateral severe flexion contracture, and anesthesia difficulties—that is, patients who are anatomically or medically difficult to anesthetize, such as some adult or juvenile patients with rheumatoid arthritis or patients with severe ankylosing spondylitis.

Relative indications for bilateral simultaneous TKA include the need for multiple additional surgical procedures to achieve satisfactory function and financial or social considerations for the patient.

Contraindications to bilateral TKA include medical infirmity (especially cardiac), a reluctant patient, and a patient with a very low pain threshold. Advanced age (octogenarian or above) is only a relative contraindication.1

Anesthetic Considerations

In performing bilateral TKA, regional anesthesia has been preferred. Traditionally, it is in the form of epidural anesthesia with an indwelling catheter. The catheter is maintained in place for 24 to 48 hours, at which time it is capped or removed and oral medications are substituted. Alternatively, general anesthesia with bilateral femoral nerve blocks can be used. With the advent of pericapsular injection techniques, anesthetic considerations will continue to evolve.

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is initiated with a loading dose of warfarin on the night before surgery. The dose varies between 4 and 10 mg, depending on the size, age, and medical status of the patient. During the hospitalization, the international normalization ratio (INR) is adjusted to between 1.8 and 2.2 by varying the warfarin dose. It generally takes 2 to 3 days for the INR to come into range, allowing the epidural catheter to be left in place for 48 hours and safely removed before the patient has received excessive anticoagulation therapy. Occasionally, this goal is not met and the catheter must be kept in place (capped) until the INR drifts down into a safe range. The safe range varies somewhat among anesthesiologists.

After the INR has been appropriately adjusted and the patient discharged, warfarin use continues for 4 weeks. Home or outpatient blood drawing for INR usually takes place twice weekly. After the warfarin is discontinued, the patient is switched to 81 mg of aspirin daily for a minimum of 6 weeks.

Other ancillary measures that might minimize the possibility of DVT include use of an epidural for anesthesia, pulsatile compression stockings applied immediately postoperatively, and early (same day) patient mobilization with standing and short-distance ambulation.