Bicycling Injuries

Chad A. Asplund

INTRODUCTION

Participation in bicycling is rapidly growing.

In 2009, 38.1 million Americans age 7 and older were estimated to have ridden a bicycle six times or more (22).

There are many different ways to participate in bicycling: road cycling, mountain biking, touring/commuting, cyclocross, and BMX.

With the increased participation, there has been an increase in both traumatic and overuse injuries:

Each year, more than 500,000 people in the United States are treated in emergency departments and more than 700 people die as a result of bicycle-related injuries (10).

Many of these overuse injuries occur secondary to improper bicycle fit or to training errors.

This chapter will outline the different ways people can participate in bicycling, the anatomy and fit of the bicycle, injury epidemiology, traumatic and overuse injuries, cycling-related equipment, and common training errors.

DIFFERENT MODES OF BICYCLING

Road Cycling

Road racing: Open road 25-100 miles.

Criterium: Multiple laps around a short course.

Very popular in America

High potential for crashing/injury

Time trial: Race against the clock with wave start with 1-5 minutes between riders.

Mountain Biking

Cross-country: Longer races over variable terrain.

Downhill: Steep downhill race where focus is on speed; injuries occur as safety is sacrificed for speed.

Dual slalom: Two racers compete in downhill ski-style slalom course.

Touring/Commuting

Long-distance road riding for recreation. Rider may be carrying panniers/saddlebags.

Cyclocross

Off-road race on road-style bike, in which riders complete multiple short (1-2 mile) loops in a set time period. Obstacles require rider to dismount, remount, and carry bicycle over the course.

BMX/Trick Cycling

Riders compete against other riders over dirt courses of varied terrain or individually on ramps with stairs and railings, with aerial stunts. There is a high risk for injury with aerial acrobatics.

Fastest growing segment of U.S. cycling with 60,000 riders (14).

Largest portion of child and adolescent cyclists.

BICYCLE ANATOMY

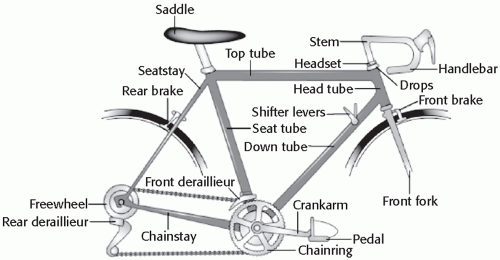

Although there are many different modes of bicycling, the general anatomy of the bicycle is similar (Fig. 88.1).

Frame Types

Standard road: Traditional upright geometry with top tube parallel to ground.

Compact road: Sloping top tube allows rider to fit smaller frame; this maximizes stiffness and minimizes weight.

Mountain/hybrid: Flatter geometry, heavier bicycle, may have front and/or rear suspension to absorb shock.

Fit

Most important attribute in the evaluation of overuse bicycling injuries.

Bicycle fit may be done at local bike shop with bicycle purchase or available for a fee.

Fit Kit and Serotta “Size Cycle” have been used (11).

Best frame size for cyclist is as small vertically as possible with enough length horizontally to allow a stretched out relaxed upper body. This frame will be lighter and stiffer and handle better (12).

Frame Size

Most important attribute for appropriate frame size is top tube length.

Top Tube Length

The ideal position varies here more than anywhere else for cyclists, depending on riding style, flexibility, body proportions, and frame geometry, among others.

Upper body position may change as riding style evolves.

May be measured by placing the elbow at the fore end of the saddle; outstretched fingers should touch the handlebars.

May also have rider, while in the drops, look straight down; the hub of the front wheel should be obscured by the handlebar.

Seat Height

Optimal saddle height has been estimated based on maximal power output and caloric expenditure (9).

Calculate height, which will be within a centimeter of 0.883 × inseam length, measured from the center of the bottom bracket to the low point of the top of the saddle. This allows full leg extension, with a slight bend in the leg at the bottom of the pedal stroke.

When seated on the bike with the pedal at the 6 o’clock position, there should be 20-25 degrees of flexion of the knee.

Alternatively, the seat may be raised until the hips start rocking when pedaling and then the seat is lowered until the rocking disappears.

Saddle Position

Check the position of the forward knee relative to the pedal spindle; for a neutral knee position, you’ll be able to drop a plumb line from the tibial tubercle and have it bisect the pedal spindle (knee over pedal spindle [KOPS] position) (9).

Handlebar Position

Most cyclists select a bar that is just as wide as their shoulders.

A wider bar opens the chest for better breathing and more leverage but sacrifices aerodynamics.

A narrower bar increases aerodynamics but sacrifices stability.

Handlebar height should be at or below the saddle height; how far below depends on the flexibility and experience of the cyclist.

Crank Arm Length

Length is based on size and riding style. Shorter crank arm length is better for quick acceleration. Long crank arms are better for pushing larger gears at a lower cadence (12).

To minimize oxygen consumption, crank arm length is dependent on femur length.

2.33 × femur length + 55.8 cm (28). This roughly translates to:

Frame size < 54 cm: 170-cm crank arm

Frame size 55-61 cm: 172.5-cm crank arm

Frame size > 61 cm: 175-cm crank arm

Gearing

Chain wheels: Large chain ring (usually 53 teeth) and small chain ring (usually 39 teeth) 53/39; recently, a more compact 50/34 chain ring combination has become more popular to allow riders to climb hills and spin at higher cadence.

Cassette: Cluster of gears (cogs) mounted to right of rear wheel.

Gear ratio: Number of teeth on chain ring divided by number of teeth on selected cog.

Higher ratio requires more strength, endurance, and technique.

Lower gear ratio allows for more spinning and higher cadence; without proper technique will yield less power.

Cadence

Optimal cadence determined by type of race (time trial, climbing, criterium), body type, muscle fiber type, and training level (8).

Higher cadences put less strain on trained leg muscles.

Low cadences increase intramuscular pressure, reducing blood flow to the muscles during the power phase of the pedal stroke.

High-cadence/low-resistance training reduces the incidence of overuse injuries. Cyclists beginning a season or returning from injury should return with this type of training.

Cadence is individual and should be determined on a rider-by-rider basis.

INJURIES

Epidemiology

Each year, more than 500,000 bicyclists in the United States are treated in emergency departments, and more than 700 people die as a result of bicycle-related injuries (8).

Children are at particularly high risk for bicycle-related injuries. In 2001, children 15 years and younger accounted for 59% of all bicycle-related injuries seen in U.S. emergency departments.

Peak incidence of bicycle-related injuries is in the 9- to 15-year-old age group.

Bicycle crashes are the second leading cause of sports-associated serious injury (riding animals is the leading cause) (26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree