, Antonio Cesarani2 and Guido Brugnoni3

(1)

“Don Carlo Gnocchi” Foundation, Milano, Italy

(2)

UOC Audiologia Dip. Scienze Cliniche e Comunità, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

(3)

Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy

Abstract

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo, and it is recognized to be a pure inner ear problem that results in short-lasting, but severe, room-spinning vertigo generally provoked by movement of the head or changing position in bed. Cupulolithiasis and canalolithiasis have both been proposed as pathophysiologic biomechanical models underlying BPPV. On the basis of these models, manoeuvres aimed to the “liberation” of the cupula or the canal have been proposed, and most cases of BPPV can be treated using Semont’s liberatory manoeuvre in the case of cupulolithiasis or Epley’s canalith-repositioning procedure (CRP) and Lempert’s “barbecue manoeuvre” in the case of canalolithiasis. These manoeuvres are sometimes unsuitable for patients with cervical or back disorders, especially for older patients. In this kind of patients, it is thus better to use more conservative procedures like the supine to prolonged lateral position (SPLP) or the rolling over manoeuvre (ROM). The treatment proposed in this chapter combines different steps: (1) high-velocity low-range epigastric supported manipulation of the middle thoracic joint (Th7–8 segment), (2) high-velocity low-range sternum supported manipulation of the cervicothoracic (C7–Th1–2 segment), (3) treatment of the cervical soft tissues and (4) proper liberatory manoeuvre.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo [1]. The lifetime prevalence of BPPV is 2.4 %, and the 1-year incidence is 0.6 % [2]. In the majority of cases, the aetiology of idiopathic BPPV is still nowadays unclear. Secondary BPPV is less common and may result from several pathological conditions such as head trauma, surgery, infection, vertebrobasilar insufficiency or inner ear diseases [3, 4].

BPPV is recognized to be a pure inner ear problem that results in short-lasting, but severe, room-spinning vertigo generally provoked by movement of the head or changing position in bed. It was described in Barany’s (1907) works [cited in 5], but it gained its definite clinical through the report of Dix and Hallpike [6].

The principal complaint is the occurrence of sudden attacks of vertigo precipitated by certain head positions. The attacks can be induced by rolling over bed, to one side and to both sides; by sudden movement of the head; by extending the neck; by looking upward, as reaching for an object from the top shelf in the kitchen; by bending the head backward for hair washing; by lying down beneath a car; or by throwing the head backward to paint a ceiling. The patient sometimes recognizes that the onset of the vertigo is associated with this critical position and will say he or she does his or her best to avoid it.

The initial occurrence is usually experienced on awakening in the morning, which is considered characteristic, or during the night. Many patients are frightened by the intense vertigo and try to shut out the sensation by closing their eyes. Nausea, often accompanied by anxiety, even vomiting, may follow the attack in few cases. In rare cases, the nausea persists for hours. Vertigo is of short duration (<1 min), but because of the intensity of the vertiginous sensation, a longer duration can be assigned to the attack.

Generally speaking, two main kinds of BPPV can be recognized:

1.

Vertigo elicited by the so-called Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre [6] accompanied by a typical horizontal-rotary geotropic nystagmus while the patient is supine during simultaneous rotation and hyperextension of the head. Nystagmus appears immediately or few seconds after the execution of the manoeuvre (latency); it increases paroxysmally for few seconds and exhausts in less than 1′, and it is decreased by the following repetition of the same manoeuvre (fatigability due to habituation phenomena). In some cases, no nystagmus is observed, but the patient complains of vertigo with the same characteristic of latency, paroxysm, exhaustion and fatigability.

2.

Vertigo and pure horizontal nystagmus provoked by rolling the head from side to side while the patient is recumbent. In this case (so-called Pagnini–McClure manoeuvre [7, 8]), two kinds of nystagmus can be observed, geotropic or ageotropic nystagmus. Generally, this kind of BPPV is long-lasting and may appear without latency.

The characteristic presentation of this disorder involves repeated episodes of transient illusion of spinning, triggered by head motion in the plane of the involved semicircular canal (SCC). Cupulolithiasis and canalolithiasis [9] have both been proposed as pathophysiologic biomechanical models underlying BPPV.

According to the cupulolithiasis model, originally described by Schucknecht [10], substances having a specific gravity greater than the endolymph, and thus subject to movement with changes in the direction of gravitational forces, come into contact with the cupula of the posterior semicircular canal (in the case of vertigo induced by Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre) or of the lateral semicircular canal (in the case of vertigo elicited by Pagnini–McClure manoeuvre). The change of position of the labyrinth during movement of the head provokes the displacement of the cupula by direct influence of these heavy substances on it. According to the canalithiasis model, during head movements, free-floating particles move within the affected SCC stimulating the cupula in a pathological way.

Signs (nystagmus) and symptoms (nausea, vertigo, etc.), manifest during provocative tests for the disorder, fall into two main categories: tonic and phasic. Tonic responses include maintained ocular nystagmus that is initiated immediately upon reorientation of the head relative to gravity. This condition, typically associated with the pathological presence of a heavy particulate mass adhered to a cupula, is correlated to cupulolithiasis model [9]. In contrast, phasic symptoms occur with a delayed onset and subside over time. These responses are typically attributed to the canalithiasis model [9].

On the basis of these models, manoeuvres aimed to the “liberation” of the cupula or the canal from heavy particles (generally residual of otoconia metabolism) have been proposed, and most cases of BPPV can be treated using physical therapy, Semont’s [11] liberatory manoeuvre in the case of cupulolithiasis, Epley’s [12] canalith-repositioning procedure (CRP) and Lempert’s “barbecue manoeuvre” [13] in the case of canalolithiasis.

In these years various modifications of these three “basic” manoeuvres have been proposed, but for the scope of this book, we prefer to present only them and our personal treatment of BPPV.

8.1 Semont’s Manoeuvre

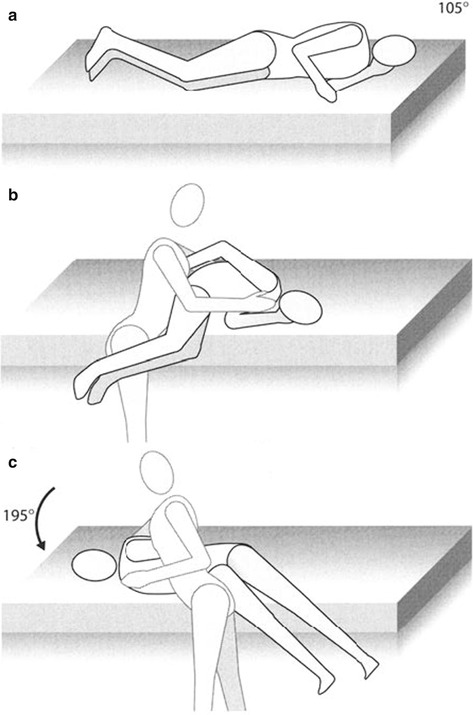

The patient lies on the affected side for at least 3 min (in Fig. 8.1a, a left PPV is represented). Then the head is rotated upward about 105° in order (according to the cupolithiasis model) to allow the displacement of the heavy particles at the basis of the posterior semicircular canal with downward deflexion of the cupula. Then the therapist takes firmly the head of the patient (Fig. 8.1b), and decisively he or she brings the patient on the opposite side with a contemporary rotation of the head downward about 195° (Fig. 8.1c). Usually, in this position, after few seconds, a “liberatory” nystagmus toward the affected side appears. When nystagmus and vertigo disappear, the patient returns slowly in sitting position

Fig. 8.1

(a–c) Semont’s manoeuvre (Originally published in Cesarani and Alpini [36] published by Springer © 1999)

8.2 Epley’s Manoeuvre

According to the original description of the technique, the patient is premedicated with transdermal scopolamine the night before or diazepam 5 mg. Nowadays, premedication is usually not necessary; even in very anxious patients, administration of diazepam 5 mg per os 2–3 h before treatment may be useful.

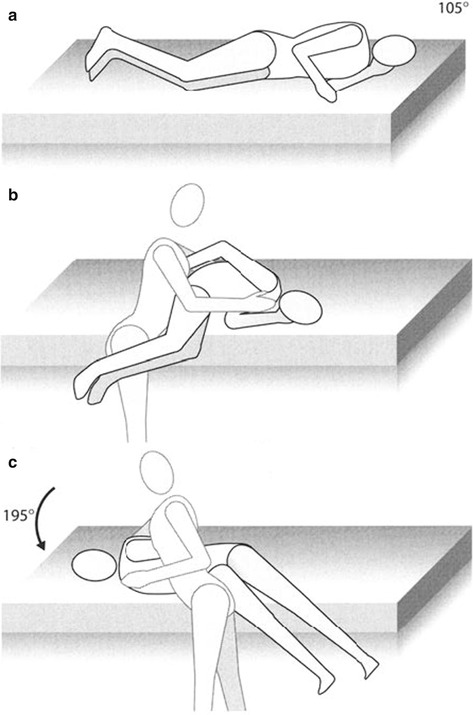

The patient is seated on an examining table (Fig. 8.2a) so that when the patient is brought to the supine position, the head extends beyond the bed. The operator is located directly behind the patient and an assistant at the patient’s side.

Fig. 8.2

(a–e) Epley’s manoeuvre (Originally published in Cesarani and Alpini [36] published by Springer © 1999)

According to the original description of the technique, throughout the positioning manoeuvres, oscillations of the skull are optionally induced. The hand-held oscillator with a frequency of approximately 80 Hz does not actually touch the head but acts through the operator’s hand applied to the ipsilateral mastoid process.

The patient lies downward with a slight hyperextension of the head and a contemporary 105° rotation toward the affected side (in the case of the figures, the left, Fig. 8.2b). In this position, nystagmus and vertigo appear. The patient remains in each position 6–13 s but may extend to more than 30 s. Then the head is rotated on the opposite side toward the healthy labyrinth for 90° (Fig. 8.2c). Simultaneous to head rotation, also the trunk and the legs rotate toward the healthy side (Fig. 8.2d). In this position, usually, a “liberatory” nystagmus is observed. Then the patient completes the rotation of the legs and returns in sitting position keeping the head turned toward the opposite side with respect to the affected labyrinth (Fig. 8.2e).

8.3 Lempert’s Manoeuvre

This manoeuvre represents an adaptation of Epley’s posterior canal repositioning procedure, and it aims to shift heavy particles (according to the canalolithiasis model) ampullofugally toward and beyond the horizontal canal opening into the utricle. The manoeuvre consists of 270° head rotation around the supine patient’s longitudinal axis; the rotation is performed in rapid steps of 90°. The patient is in recumbent position. Then the head is rotated toward the affected side (Pagnini–McClure position). In this position, nystagmus is elicited. When vertigo and nystagmus disappeared, the therapist performs a complete rotation of the head and the body of the patient in step of 90° until a complete 270° rotation. Head positions are maintained for between 30 and 60 s until all nystagmus has subsided.

In the case of geotropic nystagmus, the first rotation of the head is toward the opposite side, while in the case of ageotropic nystagmus, the first rotation of the head is in the direction of the affected ear.

8.4 BPPV Treatment in Elderly and/or Difficult Patients

Although the described manoeuvres have been shown to have therapeutic benefits, they require sequential procedures involving moving the patient’s head and body into unnatural positions, making them sometimes unsuitable for patients with cervical or back disorders, especially for older patients.

In this kind of patients, it is thus better to use more conservative procedures like the supine to prolonged lateral position (SPLP) [14] or the rolling over manoeuvre (ROM) [15].

SPLP contained two steps. First, the patient was instructed to start in an upright sitting position and then lie down supinely on the bed and maintain this position for 3 min. During this step, it was proposed that the trapped otolithic particles would move away from the ampulla (ampullofugal), drift toward the common crus by crossing the horizontal SCC plane and stay in the superior arm of the posterior SCC. In the second step, the patient was asked to sleep on their healthy side by turning their head and body from the previous supine position toward the healthy side laterally. This process allowed the particles to slip through the common crus into the utricle. To facilitate their movement back into the utricle and to prevent any floating particles in the utricle from being trapped in the posterior SCC again, a prolonged side lateral position (minimum duration 30 min) was suggested at bedtime, with or without a pillow support.

ROM involves moving the patient from supine to nose-up position to a right ear-down position and maintaining this position for 10 s, before subsequently returning the head to a nose-up position, which is maintained for further 10 s. The patient is then moved to the left ear-down head position which is maintained for 10 s. The patient repeats these manoeuvres 10 times in a set and 2 sets in a day, before getting up in the morning and before sleeping in the night.

ROM can be performed either by neck rotation or by whole-body movements without any cervical torsion. This is very suitable for whiplash patients, especially in the early phases of trauma.

8.5 Personal Approach to BPPV

The heavy particles attached to the cupula or free-floating into the canals may be derived by residual of otoconia metabolism, otoconia fragments displaced by a head or a whiplash trauma, inflammatory material or any other pathological particles produced during the course of a systemic (i.e. autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes, hyperuricaemia, etc.) or an inner ear disorder (i.e. vestibular neuronitis, Ménière’s disease, etc.). In all the cases, through the natural course of endolymph renewal or by means of liberatory manoeuvres, these particles are expelled to the inner ear venous system and thus to the cervical venous system. The cervical venous drainage is composed of the internal jugular veins anteriorly and the vertebral venous system posteriorly. The latter is composed of the external and internal vertebral venous plexuses, which are anastomosed by way of the intervertebral and basivertebral veins [16]. The venous vertebral system is composed of plexuses along all the spine from the skull until the lumbar region, and thus, in our experience, combining “liberatory” manoeuvres with manual techniques and some suggestions (see Sect. 8.5.3) aimed to facilitate the drainage of the inner ear improve the efficiency of BPPV treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree