6 Basic spinal NMT

Defining NMT

NMT, as the term is used in this book, is summarized in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1 Aims of NMT and allied approaches

• Neuromuscular technique, as the term is used in this book, refers to the manual application of specialized pressure and strokes, usually delivered by a finger or thumb contact, which have a diagnostic (assessment mode) or therapeutic (treatment mode) objective.

• Therapeutically, NMT aims to produce modifications in dysfunctional tissue, encouraging a restoration of normality, with a primary focus of deactivating focal points of reflexogenic activity such as myofascial trigger points.

• An alternative focus of NMT application is towards normalizing imbalances in hypertonic and/or fibrotic tissues, either as an end in itself or as a precursor to joint mobilization/rehabilitation.

• NMT utilizes physiological responses involving neurological mechanoreceptors, Golgi tendon organs, muscle spindles and other proprioceptors, in order to achieve the desired responses.

• Insofar as they integrate with NMT, other means of influencing such neural reporting stations, including positional release (strain/counterstrain) and muscle energy methods (such as reciprocal inhibition and post-isometric relaxation induction) are seen to form a natural set of allied approaches.

• Traditional massage methods that encourage a reduction in retention of metabolic wastes and enhanced circulation to dysfunctional tissues are included in this category of allied approaches.

The other NMT version described is the American NMT model, that resulted from the original work of Nimmo, Simons and Travell – with further development by St John and Walker, among others (see Chapters 10 and 13).

A confusing element relating to the term NMT emerges, because of its use by Dvorak et al (1988), when they describe what are, in effect, variations on the theme of the use of isometric contractions in order to encourage a reduction in hypertonicity. These methods, all of which form part of what is known as muscle energy technique (MET) in osteopathic medicine and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) in physiotherapy, are described briefly in Chapter 8, and form the focus of a further title in the series of which this book is part (Chaitow 2001, 2006).

Dvorak et al (1988) have listed various MET methods (as NMT) as follows:

1. Methods that involve self-mobilization by patient action, to encourage movement past a resistance barrier, are described as ‘NMT 1’.

2. Isometric contraction and subsequent passive stretching of agonist muscles, involving postisometric relaxation, are called ‘NMT 2’.

3. Isometric contraction of antagonists, followed by stretching, involving reciprocal inhibition, are described as ‘NMT 3’.

Use of the terms NMT 1, 2 and 3 in these ways, by Dvorak et al (1988), in order to describe these methods, succeeds in adding to, rather than reducing, semantic confusion, and it is hoped that this aberrant set of descriptors will not persist.

Unique aspects of NMT

NMT can usefully be integrated in treatment that is aimed at postural reintegration, tension release, pain relief, improvement of joint mobility, reflex stimulation/modulation or sedation. There are many variations of the basic technique, as developed by Stanley Lief, the choice of which will depend upon particular presenting factors, or personal preference. Similarities between some aspects of NMT and other manual systems (see Ch. 8) should be anticipated, as techniques have been borrowed and adapted from other systems where appropriate. For example, in Chapter 11 Dennis Dowling demonstrates the clinical value of using progressive inhibition of neuromuscular structures (PINS), a unique way of utilizing NMT effects, in pain control. Use of PINS in pain control offers an example of the evolution of new applications of the basics, which NMT provides (Dowling 2000).

And just as there are current evolutionary paths involving NMT principles, so there have been parallel evolutions of methods that derive from similar backgrounds. In Chapter 12 Howard Evans describes Thai yoga massage methods that are truly a blend of the model of manual care that evolved in Thailand, based on the same root approaches deriving from Ayurvedic massage which let to Lief’s NMT. Evans’ approach is further influenced by having studied Lief’s methods giving him a useful Western and Eastern set of approaches which he has fused and described (Evans 2009).

NMT can be applied generally, or locally, and in a variety of positions (with the patient seated, supine, prone, side-lying, etc.). The order in which body areas are dealt with is not regarded as critical in general treatment, but seems to be of some consequence in postural reintegration (Rolf 1977).

In Chapter 13, Cohen describes both the historical work of Raymond Nimmo, and the continuing evolution of his methods, which form a major part of American Version NMT, as described by DeLany in Chapter 10.

Most used NMT approaches – and ‘variable pressure’

The basic spinal NMT treatment and the basic abdominal (and related areas) NMT treatment (see Ch. 7) are the most commonly used, and will be described in detail in this and the next chapter. The methods described are in essence those of Stanley Lief ND DC and Boris Chaitow ND DC, both of whom achieved a degree of skill in the application of NMT that is unsurpassed. The inclusion of data on reflex areas and effects, together with basic NMT methods, provides the practitioner with a useful therapeutic tool, the limitations of which will be determined largely by the degree of intelligence and understanding with which it is employed.

As Boris Chaitow has written (personal communication, 1983):

Thumb considerations

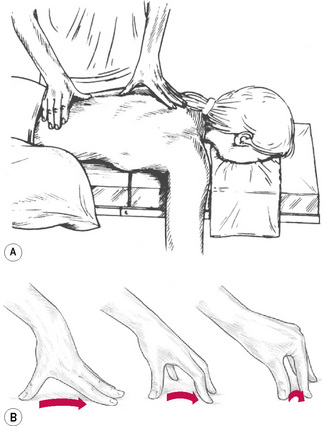

NMT thumb technique (Fig. 6.1)

NMT thumb technique (Fig. 6.1)

• For balance and control, the hand should be spread, the tips of fingers providing a fulcrum or ‘bridge’ in which the palm is arched in order to allow free passage of the thumb towards one of the fingertips as the thumb moves in a direction that takes it away from the practitioner’s body.

• During a single stroke, which covers between 2 and 3 inches (5–8 cm), the fingertips act as a point of balance, while the chief force is imparted to the thumb tip via controlled application through the long axis of the extended arm of body weight.

• The thumb, therefore, never leads the hand but always trails behind the stable fingers, the tips of which rest just beyond the end of the stroke.

• Unlike many bodywork/massage strokes, the hand and arm remain still as the thumb, applying variable pressure (see below), moves through its pathway of tissue.

• The extreme versatility of the thumb enables it to modify the direction of imparted force in accordance with the indications of the tissue being tested or treated.

• As the thumb glides across and through those tissues it becomes an extension of the practitioner’s brain. In fact, for the clearest assessment of what is being palpated, the practitioner should have the eyes closed, in order that every minute change in the tissue can be felt and reacted to.

• The thumb and hand seldom impart their own muscular force, except in dealing with small localized contractures or fibrotic ‘nodules’.

• In order that pressure/force be transmitted directly to its target, the weight being imparted should travel in as straight a line as possible, which is why the arm should not be flexed at the elbow or the wrist by more than a few degrees. The positioning of the practitioner’s body in relation to the area being treated is also of the utmost importance in order to facilitate economy of effort and comfort.

• The optimal height vis-à-vis the couch, and the most effective angle of approach to the body areas being addressed, must be considered and the descriptions and illustrations will help to make this clearer.

• The degree of pressure imparted will depend on the nature of the tissue being treated, with a great variety of changes in pressure being possible during strokes across and through the tissues. When being treated, the patient should not feel strong pain, but a general degree of discomfort is usually acceptable as the seldom stationary thumb varies its penetration of dysfunctional tissues.

• A stroke or glide of 2–3 inches (5–8 cm) will usually take 4–5 seconds – seldom more unless a particularly obstructive indurated area is being dealt with. If reflex pressure techniques are being employed, a much longer stay on a point will be needed, but in normal diagnostic and therapeutic use the thumb continues to move as it probes, decongests and generally treats the tissues.

• It is not possible to state the exact pressures necessary in NMT application because of the very nature of the objective, which in assessment mode attempts to meet and match the tissue resistance precisely, to vary the pressure constantly in response to what is being felt.

• In subsequent or synchronous (with assessment) treatment of whatever is uncovered during evaluation, a greater degree of pressure is used and this too will vary, depending upon the objective – whether this is to inhibit, to produce localized stretching, to decongest and so on. Obviously, on areas with relatively thin muscular covering, the applied pressure would be lighter than in tense or thick, well covered areas such as the buttocks.

• Attention should also be paid to the relative sensitivity of different areas and different patients. The thumb should not just mechanically stroke across or through tissue but should become an intelligent extension of the practitioner’s diagnostic sensitivities so that the contact feels to the patient as though it is sequentially assessing every important nook and cranny of the soft tissues. Pain should be transient and no bruising should result if the above advice is followed.

• The treating arm and thumb should be relatively straight because a ‘hooked’ thumb, in which all the work is done by the distal phalange, will become extremely tired and will not achieve the degree of penetration possible via a fairly rigid thumb.

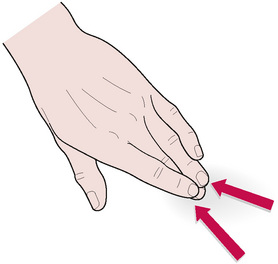

NMT finger technique (Fig. 6.2)

NMT finger technique (Fig. 6.2)

• The middle or index finger should be slightly flexed and, depending on the direction of the stroke (most usually toward the practitioner) and density of the tissues, supported by one of its adjacent members.

• As the treating finger strokes with a firm contact, and usually a minimum of lubricant, a tensile strain is created between its tip and the tissue underlying it.

• This is stretched and lifted by the passage of the finger which, like the thumb, should continue moving unless or until dense, indurated tissue prevents its easy passage. When treating, these strokes can be repeated once or twice, as tissue changes dictate.

• The angle of pressure to the skin surface is between 40° and 50°.

• The fingertip should never lead the stroke but should always follow the wrist, the palmar surface of which should lead, as the hand is drawn towards the practitioner. It is possible to impart a great degree of ‘pull’ on underlying tissues, and the patient’s reactions must be taken into account in deciding on the degree of force to be used. Transient pain, or mild discomfort, is to be expected, but no more than that. All sensitive areas are indicative of some degree of dysfunction, local or reflex, and are thus important, and their presence should be recorded. The patient should be told what to expect, so that a cooperative, unworried attitude evolves.

• As mentioned above, unlike the thumb technique, in which force is largely directed away from the practitioner’s body, in finger treatment the motive force is usually towards the practitioner.

• The arm position therefore alters, and a degree of flexion is necessary to ensure that the pull, or drag, of the finger across the lightly lubricated tissues is smooth.

• Unlike the thumb, which makes a sweep across the palm towards the fingertips, whilst the rest of the hand remains relatively stationary, the whole hand will move when finger technique is applied.

• Certainly some variation in the degree of angle between fingertip and skin is allowable during a stroke, and some slight variation in the degree of ‘hooking’ of the finger is sometimes also necessary.

• However, the main motive force is applied by pulling the slightly flexed, middle or index, finger towards the practitioner, with the possibility of some lateral emphasis if needed. The treating finger should always be supported by one of its neighbours.

Use of lubricant

If a stimulant effect is required (see notes on Connective tissue massage in Chapters 4 and 5), possibly in order to achieve a rapid vascular response, then no lubricant should be used.

• Superficial stroking in the direction of lymphatic flow

• Direct pressure along the line of axis of stress fibres

• Deeper alternating ‘make and break’ stretching and pressure efforts

• Subtle weaving, insinuating, movements that attempt to melt into the tissues to obtain information or greater access

• Crowding of bunched tissues toward the direction in which they are shortening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree