7 Basic abdominal and pelvic NMT application

Objectives

1. To attempt to normalize local soft tissue dysfunction and pain (including symptoms produced by myofascial trigger points) resulting from postural or overuse strain (occupational or leisure activities, patterns of use, overload, repetition of movement, lifting, etc.), breathing pattern disorders, obesity, visceroptosis (causing drag of supporting structures, and associated congestion).

2. To enhance relaxation and reduction in symptoms relating to emotional or stress influences, particularly long-held psychological distress.

3. To improve function when the area has been traumatized (accidents, blows, surgery, etc.).

4. To influence internal organ function via reflex stimulation, for example using neurolymphatic (Chapman) reflexes and/or acupuncture points (see Ch. 4).

5. To modify painful and distressing symptoms such as those associated with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), interstitial cystitis and urgency (Weiss 2001). See Box 7.1 for details of research into such influences.

6. To attempt to improve function of the abdomino-pelvic organs by directly influencing circulatory and drainage functions (including lymphatic function) of the region (Wallace et al 1997).

7. To modify the negative local effects of viscerosomatic influences (see Ch. 3).

Box 7.1 Pelvic disease study

Between September 1995 and November 2000, 45 women and 7 men, including 10 with interstitial cystitis and 42 with the urgency–frequency syndrome, were treated once or twice weekly for 8–12 weeks, using manual therapy applied to the pelvic floor, aimed at decreasing pelvic floor hypertonus and deactivating trigger points (Weiss 2001).

Somaticovisceral symptoms

In Chapter 3 there was discussion of the phenomenon in which organ dysfunction reflects reflexogenically to the soma particularly as areas of segmental facilitation (sensitization) in the spinal region. These are, of course, the viscerosomatic reflexes. Later in this chapter possible variations on causes of viscerosomatic reflex pain will be outlined.

Simons et al (1999) reverse the consideration when they report details of somatovisceral responses, particularly arising from abdominal musculature, influencing internal visceral organs and functions.

Junctional tissues

Simons et al (1999) have discussed the sites of trigger points as falling largely into two categories:

• Lateral aspect of the rectal muscle sheaths

• Attachments of the recti muscles and external oblique muscles to the ribs

• The xiphisternal ligament, as well as the lower attachments of the internal and external oblique muscles

• Intercostal areas from 5th to 12th ribs are equally important

• Scars from previous operations may be the site of formation of connective tissue trigger points (Simons et al 1999). After sufficient healing has taken place, these incision sites can be examined by gently pinching, compressing and rolling the scar tissue between the thumb and finger to examine for evidence of trigger points, as discussed in earlier chapters (Chaitow & DeLany 2000).

Assisting organ dysfunction

Specific general areas are worthy of consideration in treating conditions that affect particular organs or functions, based on the evidence of the different reflex systems described in Chapter 4 (see also notes on percussive methods, such as spondylotherapy, in Chapter 8) (Baldry 1993, Chaitow & DeLany 2000, Fitzgerald et al 2009, Kuchera & Kuchera 1994, Wallace et al 1997):

• Liver dysfunction and portal circulatory dysfunction calls for special attention to the right-side intercostal musculature, from the 5th to the 12th ribs. Especially important are the various muscular insertions into all these ribs.

• Gall bladder dysfunction involves similar areas, with extra attention to the area on the costal margin, roughly midway between the xiphisternal notch and the lateral rib margins.

• Spleen function may be stimulated by attention to the intercostal spaces between the 7th and 12th ribs on the left side.

• Digestive disorders in general may benefit from NMT applied to the central tendon, between the recti, and directly to the rectal sheaths.

• Stomach pain is treated via its reflex area to the left of the xiphisternal notch and to the tendon and rectal sheaths.

• Colonic problems and ovarian dysfunction may benefit from reflex NMT application to both iliac fossae as well as to the midline structures.

• Dysfunction of the kidneys, ureters and bladder requires attention to the inguinal borders of the internal and external oblique insertions, the suprapubic insertions of the recti, the overlying muscles and sheaths of the area, and the internal aspects of the upper thigh.

• In pelvic congestion relating to gynaecological dysfunction, NMT should be applied to the hypogastrium and both iliac fossae. This appears to relieve congestion and stimulates pelvic circulation.

• Ileitis and other functional disturbances of the transverse colon and small intestine may benefit from NMT applied to the umbilical area.

• Prostatic dysfunction may benefit from NMT to the central hypogastric region. Internal drainage massage of the prostate should also be considered.

The above brief indications should be considered in conjunction with other reflex systems and points (see below), as well as attention to the appropriate spinal areas (see notes on facilitation in Ch. 3), which may also benefit from NMT.

More on abdominal reflex areas

Gutstein (1944) noted ‘trigger areas’ in the sternal, parasternal and epigastric regions, and in the upper portions of the recti muscles, all relating to varying degrees of retroperistalsis. He also noted that colonic dysfunction related to triggers in the mid and lower recti muscles. These were all predominantly left-sided.

Fielder & Pyott (1955) described a number of reflexes occurring on the large bowel itself. These could be localized by deep palpation and treated by specific release techniques (see Chapter 8, and Figure 8.21). These reflexes palpate as areas of tenderness, and may include a degree of swelling and congestion resulting from adhesions, spasticity, diverticuli, chemical or bacterial irritation, etc.

In considering the reflexes available for therapeutic intervention, in the thoracic and abdominal regions, the neurolymphatic points of Chapman are worthy of close attention (see Chapter 4 for more detail). When applying NMT in its evaluative mode, to the anterior thorax and abdomen (as described later in this chapter), an awareness of the reflexes described by Chapman (Owen 1980) is a distinct advantage, especially if there is a need to take account of visceral or thoracic organ dysfunction.

Kuchera (1997) notes:

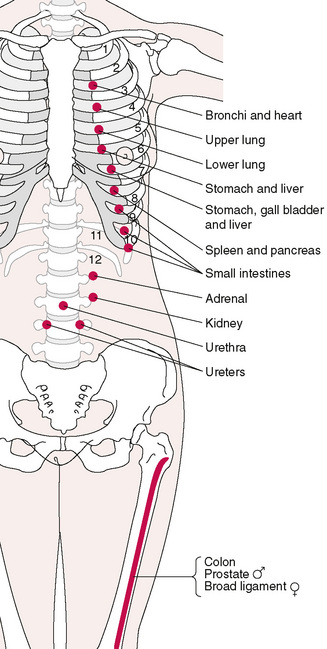

See Figure 7.1 for the location of common abdominally related reflexes noted in this region (and also Figs 5.8A,B).

Discussion

To what extent Gutstein’s myodysneuric points are interchangeable with Chapman’s, or Fielder’s, reflexes, or other systems of reflex study (e.g. acupuncture or tsubo points or Travell’s trigger points), and to what extent these involve Mackenzie’s work (Mackenzie 1909) as illustrated in Figure 5.4, is a matter for further research.

Many of Jones’ (positional release/strain/counterstrain) tender points (see Figure 4.5A) are located in the abdominal region, specifically relating to those strains that occur in a flexed position (Jones 1981).

Bennett’s neurovascular points (see Chapter 4 and Figure 5.9A) are located mainly on the anterior aspect of the body, and may be located during abdominal NMT work. This may be a link with the work of Mackenzie and others, who have demonstrated a clear relationship between the abdominal wall and the viscera. This and other reflex patterns provide the rationale for NMT application to the abdominal and sternal regions.

Baldry (1993) details a huge amount of research that validates the link (a somatovisceral reflex) between abdominal trigger points, and symptoms as diverse as anorexia, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, colic, dysmenorrhoea and dysuria.

Pain of a deep aching nature, or sometimes of a sharp or burning type, is reported as being associated with this range of symptoms, which mimic organ disease or dysfunction (Fitzgerald et al 2009, Melnick 1954, Ranger et al 1971, Travell & Simons 1983).

Baldry (1993) has further summarized the importance of this region as a source of considerable pain and distress involving pelvic, abdominal and gynaecological symptoms. He says:

Is the pain in the muscle or an organ?

Is the pain in the muscle or an organ?

• The supine patient is then asked to raise both (straight) legs from the table (heels must be raised by several inches).

• As this happens there will be a contraction of the abdominal muscles, which produces a compression of the trigger point between the muscle and the finger/thumb, and pain should increase.

• If pain decreases on the raising of the legs, the site of the pain is beneath the muscle and probably involves a visceral problem (Thomson & Francis 1977).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree