Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

Jon E. Browne

James E. Voos

Thomas P. Branch

DEFINITION

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) was first described by Brittberg et al2 in 1994 in which articular cartilage is harvested, enzymatically prepared to isolated chondrocytes, cultured to undergo proliferation, and transplanted into an articular cartilage defect to produce “hyaline-like” cartilage.

Browne and Branch3 divided articular cartilage surgical options into reparative and restorative categories. Reparative procedures, such as microfracture, although efficacious in some clinical studies, result in primarily a fibrocartilage repair tissue. Restorative procedures, such as osteochondral autograft transfer and ACI, result in repair tissue with higher concentrations of chondrogenic cells and type II collagen present in native articular cartilage. ACI preserves the subchondral plate below the articular cartilage, whereas microfracture disrupts this native architecture.

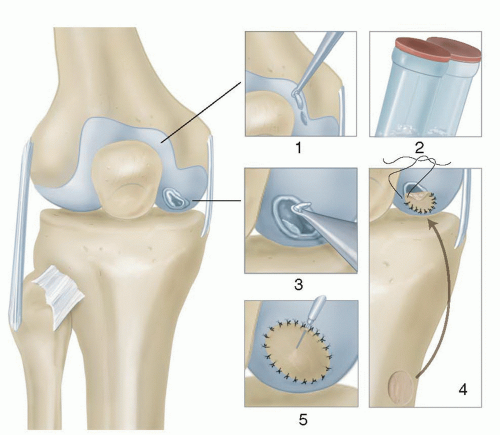

ACI is performed as a two-stage procedure (FIG 1). In the first stage, articular cartilage is biopsied from the periphery of the femoral condyle either medial or lateral. The cells are then cultured and subsequently reimplanted during the second stage. First-generation ACI uses a periosteal patch sutured over the defect that serves to contain the cells. This technique has resulted in an elevated reoperation incidence typically due to periosteal patch hypertrophy with rates up to 50%.1,8,10,14,17 Second- and third-generation ACI has been described using a collagen membrane (C-ACI) and membrane-associated (MACI) techniques.8,15,22,23,26 These newer generation techniques result in less morbidity due to avoidance of periosteal patch harvest and graft hypertrophy rates as low as 5%.8

Currently, MACI is not approved for use in the United States. Collagen membranes are currently considered off-label use for articular cartilage procedures and approved primarily for indications of rotator cuff repair, tendon augmentation procedures, as well as dental applications. Therefore, this chapter will focus on first-generation periosteal patch ACI and C-ACI techniques.

ANATOMY

Knowledge of articular cartilage anatomy is paramount to understanding articular restoration or reparative techniques. Articular cartilage is divided into four distinct zones: superficial, middle, deep, and calcified.3

Articular cartilage is a viscoelastic material made up of chondrocytes (1% to 5%), water (75%), collagen (10%), and proteoglycans (10%).3,25 Chondrocytes are the primary cell in articular cartilage that originate from undifferentiated mesenchymal marrow stem cells. The extracellular matrix consists of type II collagen (95%) and smaller amounts of collagen types IV, VI, IX, X, and XII that provide the tensile strength. Chondroitin and keratin sulfate are negatively charged proteoglycans that attract and hold water while providing the compressive strength.

Knee articular cartilage varies from 2 to 6 mm in thickness based on peak contact pressures. It is aneural and lacks a vascular or lymphatic supply. Nutritional supply and removal of metabolites are provided by the synovial fluid.

Mechanisms of Articular Cartilage Function

An understanding of the mechanisms of articular cartilage function is critical to the surgeon’s decision-making process when choosing between reparative and restorative procedures for treatment of cartilage injuries. Without this knowledge, the simpler and easier techniques of cartilage repair may be selected in lieu of the better long-term solutions of articular cartilage restoration. The direction of modern tissue engineering is directly toward mimicking the tribologic characteristics of native articular cartilage.16

There are three main mechanisms for the low-friction properties of articular cartilage. The first mechanism relies on the structural characteristics of the surface of the superficial layer. The lamina splendens has a horizontal mat of type II collagen fibrils which when viewed on electron microscopy is extremely smooth. The cell density within the superficial layer is the greatest and designed to resist the shear forces present during articulation.7,28

The second mechanism involves lubrication of the articular cartilage and can be characterized by fluid film and boundary lubrication. Fluid film lubrication occurs when the two surfaces are separated by the thickness of a viscous fluid greater than the surface aberrations preventing structure to structure contact.20 Boundary lubrication occurs at the microfilm level where molecules such as phospholipids plant their hydrophobic body toward the articular cartilage and point their hydrophilic tail toward the opposite articular cartilage.19

Finally, “weeping” lubrication may impact articular cartilage friction by releasing interstitial fluid from compressed cartilage, creating a flow effect.13 “Boosted” lubrication may occur, forcing fluid back into the extracellular matrix, thus increasing lubricant at the joint interface.27 All of these mechanisms for optimizing articular cartilage friction properties to the lowest possible degree are unlikely to be found in reparative procedures for articular cartilage injuries and have a higher chance of success as surgeons attempt to develop restorative procedures for articular cartilage injuries such as ACI.

PATHOGENESIS

Articular cartilage injuries most commonly occur in the setting of a traumatic injury to the knee. This may occur via three mechanisms, the first being a direct blow to the chondral surface such as the knee striking the ground during a fall or “dashboard” injury during a motor vehicle accident. The second occurs as a result of a ligamentous injury to the knee in which ligamentous insufficiency results in abnormal translation of the knee with traumatic contact of the chondral surfaces with each other. The third results from a shear injury to the chondral surfaces during a traumatic patella dislocation.

Articular cartilage lesions can also occur as the result of more insidious causes such osteochondritis dissecans, osteonecrosis, focal degenerative changes, overload from limb malalignment, infection, and inflammatory arthritis. Lesions as the result of inflammatory arthritis, infection, or bipolar chondral lesions Outerbridge grade III or greater are a contraindication to ACI.

It is important for the surgeon to understand the underlying biologic impact of each of these mechanisms as they have different consequences to margins and depths of the articular damage.

In a classic paper by Donohue et al,5 a lower energy direct blow to the articular cartilage can cause blistering of the articular cartilage, with advancement of the tidemark creating a lesion that has minimal effects to the subchondral bone. These injuries are more amenable to restoration through ACI. On the other hand, a higher energy mechanism that causes subchondral fracture such as patellar dislocation creating a fracture or ligament loss that causes larger, irregular surface area lesions with damage to the subchondral bone may be a less successful candidate.6,11,12

NATURAL HISTORY

Articular cartilage lesions have a limited capacity to regenerate due to its low mitotic rate, low turnover rate, low cellto-matrix volume, and lack of a vascular supply. Progenitor cells capable of assisting in healing are located below the calcified cartilage, so only injuries that penetrate the subchondral plate have the capacity to form a fibrin clot with resultant fibrocartilage formation.23 This results in biomechanically inferior tissue to native hyaline cartilage.

The natural history of untreated articular cartilage lesions is unknown, and to date, no formal studies have reported the results in a large cohort of patients. The progression of lesions over time is also confounded by factors such as patient age, chronicity of the lesion, limb alignment, activity level, ligamentous stability, body mass index (BMI), and status of the menisci.

Relative consensus exists among authors with regard to lesions that are amenable to treatment with ACI. This includes symptomatic lesions Outerbridge grade III or IV, International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grade 3 or 4, lesion size greater than 2 cm2, and patients aged 50 years or younger.4,9,17,23

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with articular cartilage lesions commonly present after a traumatic episode. This may occur in the setting of a concomitant ligament injury such as an anterior cruciate ligament injury during a sporting activity or from a direct impact to the cartilage such as a dashboard injury that occurs during a motor vehicle accident. Additional traumatic causes may occur in the setting of a patella instability event. Other articular cartilage lesions may present in a more insidious manner such osteochondritis dissecans, focal osteonecrosis, or early focal degenerative changes.

Patient history must also include any previous surgical procedures to the knee and complications that may have occurred. If previous surgery has been performed, review of the operative report or images is important to reveal if the subchondral bone was invaded either by the defect itself or as a result of the surgical procedure (ie, débridement, chondroplasty, microfracture, mosaicplasty, scaffold procedure). A history of violation of the subchondral bone has been shown to negatively affect the clinical outcome of ACI by weakening the construct and functioning more as a microfracture procedure producing type I collagen fibrocartilage.4 The patient can then be counseled on appropriate expectations.

Physical examination findings most commonly reveal an effusion, often accompanied by pain and quadriceps inhibition. Mechanical symptoms such as catching and locking may represent a loose body or unstable chondral flap. Palpable tenderness over the affected compartment may be present.

Assessment of the knee for standing alignment and range of motion should be performed. A thorough examination of the entire knee to evaluate concomitant pathology to the menisci and knee ligaments is critical to assure all pathology is appropriately documented and treated.

When considering ACI, the patient should be questioned for a known history of hypersensitivity to gentamicin or other aminoglycosides because this antibiotic is used in the cartilage biopsy transport media and culture media during cell processing.4

Additional considerations include assessment of patient’s BMI; willingness to comply with the extensive, and at times restrictive, rehabilitation program; and smoking status.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A complete series of plain knee radiographs including standing posteroanterior flexion, notch, tangential patellofemoral, 30- to 45-degree lateral, and long-leg standing

alignment views allow for assessment of joint space, alignment, osseous loose bodies, cystic changes, and osteophyte formation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers the most detailed modality for clear delineation of articular cartilage lesion size, involvement of subchondral bone, and location. Thin cut proton density imaging and T2-weighted imaging with fat-saturation sequences has been shown to provide optimal resolution of chondral surfaces.25 Concomitant intraarticular cartilage pathology to the menisci and ligaments is also easily visualized.

MRI is also useful to assess articular cartilage lesions after a restorative or reparative procedure has been performed to evaluate percent fill of the lesion, integration into the subchondral bone, and articular cartilage quality.

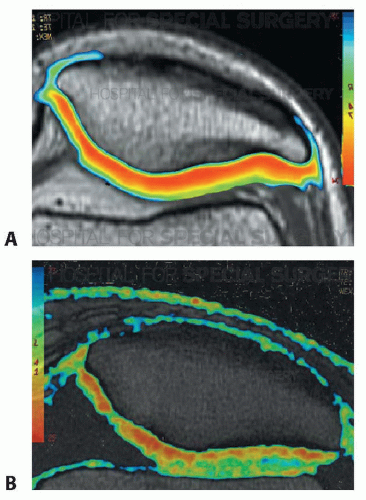

More advanced MRI techniques have recently been described to assess articular cartilage lesions.25 Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI (dGEMRIC) demonstrates the range of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) distribution in the cartilage. T2 mapping sequences allow for assessment of type II collagen fiber organization within the extra cellular matrix (FIG 2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree