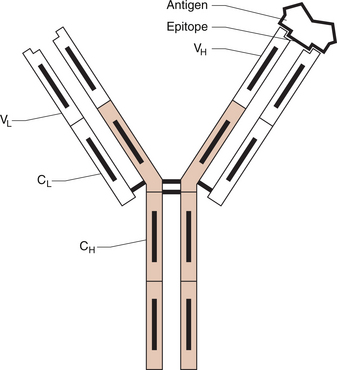

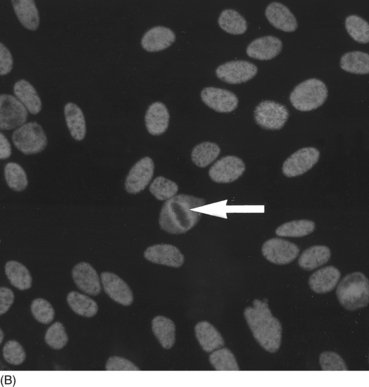

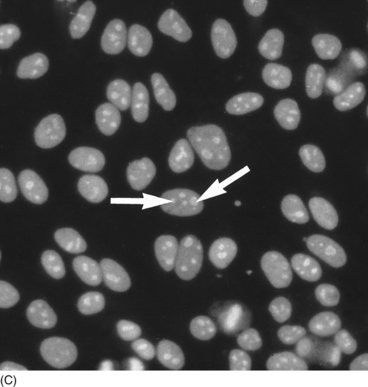

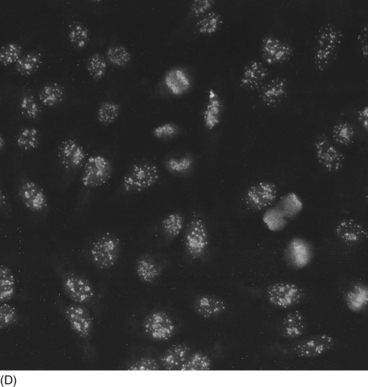

9 Nicholas Manolios Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototypic autoimmune disease, characterized by excessive auto-antibody production, immune complex formation andimmunologically-mediated tissue injury at multiple sites. It is a clinically heterogeneous disorder with a broad spectrum of presentations. Although the immune mechanism/s responsible for the breakdown of tolerance against self-antigens is unknown, a genetic influence in disease predisposition has been clearly demonstrated. Like most other connective tissue disorders, auto-antibody testing can be of value in making the diagnosis. These results must always be correlated with the patient’s symptoms and signs for correct interpretation. Treatment is symptomatic and aimed at suppressing an altered immune system that causes end-organ damage. In Chapter 1 we dealt with another autoimmune disease—rheumatoid arthritis. This chapter will be illustrated by a case of SLE that tracks its course over several years to illustrate its clinical and immunological features. Despite the heterogeneity of clinical features of SLE discussed later in this chapter, one characteristic laboratory finding is the presence of antibodies generated by the person’s own immune system against a wide range of ‘self’ antigens, such as deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA) and ribonucleoproteins. Since these antibodies are directed against ‘self’ antigens they are called ‘autoantibodies’. A schematic representation of an antigen–antibody (immune) complex is shown in Figure 9.1. The exact reason for this breakdown of immune tolerance is still unclear. The consequence of immune complex deposition in many vascular beds throughout the body results in a wide variety of clinical presentations. These manifestations are dictated by the site and extent of the inflammatory process, triggered by the antibody–antigen complex. An autoimmune disease like SLE is characterized by the production of many autoantibodies. Their exact role in disease aetiopathogenesis remains unclear. Some auto-antibodies have been shown to contribute directly to the clinical picture by causing cell death. For example, anti-erythrocyte antibodies result in haemolysis (red cell lysis) and lymphocytotoxic antibodies are responsible for the reduced lymphocyte count (lymphopenia) that occurs in active lupus. An alternative mechanism of tissue injury is deposition of antigen–antibody complexes with complement activation. This is seen particularly in the kidney and skin. Complement and pro-inflammatory cytokine production result in polymorph trafficking into the area in question. Further release of pro-inflammatory mediators from mast cells, basophils and polymorphs perpetuate the inflammatory cascade. Platelet aggregation and clot formation result in microthrombi formation and tissue ischaemia. This is compounded by the release of proteases, hydrolytic enzymes and free radicals. Complement activation may also lead both directly (via complement components C5–9) and indirectly to cell lysis. Resultant end-organ damage in various tissues such as the kidney, skin and brain are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. Under normal circumstances, antigen–antibody complexes are rapidly and efficiently cleared by phagocytes. However, defective mechanisms of immune complex clearance may perpetuate the inflammatory response. The most typical serologic abnormality in SLE is the presence of ANA antibodies. These antibodies are usually directed against intra-nuclear proteins involved in DNA packaging, RNA splicing or RNA translation. The two important features of an ANA are: (1) the titre (extent of serum dilution that still gives a detectable pattern) and (2) the pattern of immunofluorescence. The titre does not always correlate with activity, since it is the avidity of antibody binding that is important and not the amount. More than 95% of patients with SLE have a positive ANA. ANA-negative SLE is very uncommon and may be due to the presence of anti-cytoplasmic antibodies, the commonest being SS-A (also known as Ro). Our patient had a moderately positive ANA at a titre of 1/640. It is important to remember that a positive ANA is not diagnostic of SLE and can occur with other illnesses, for example bacterial and viral infection, drug therapy and other inflammatory disorders. About 5% of the normal population have a positive ANA at a titre of≥1:160. Different staining patterns (Fig. 9.2) reflect the nature of the antigen and its distribution. Their disease associations are summarized in Table 9.1. Different patterns include: Table 9.1 ANA patterns and disease associations ANA, antinuclear antibody; MCTD, mixed connective tissue disease. The extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) consist of a number of antigens which include ribonucleoprotein (RNP), Smith antigen (Sm), SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, Jo-1, ribosomal-p, and Scl-70. Their disease associations are summarized in Table 9.2. Autoantibodies can also be useful in helping with the diagnosis of connective tissue disorders (Table 9.2). The clinical findings are the most important factor in determining which autoantibody to measure. Table 9.2 Specific autoantibodies and their disease association

AUTOIMMUNITY AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Introduction

Immunology

Autoimmunity

Immunopathology

Serological manifestations of autoimmunity

Antinuclear antibodies

Titre

Staining patterns

Pattern

Antigen

Association

Homogeneous

Deoxyribonucleic acid, histones

SLE; Drug-induced lupus

Speckled

SS-A, SS-B, Sm, RNP

SLE; Sjögren’s syndrome; MCTD

Nucleolar

–

Scleroderma; Polymyositis

Centromere

Centromere

Limited Scleroderma (CREST)

Speckled and nucleolar (mixed)

SS-A, SS-B, Sm, RNP

Raynaud’s; Overlap syndromes; Myositis; Lupus; Sjögren’s

Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens

Antibody

Disease association

dsDNA

SLE

Sm

SLE

SS-A/Ro with SS-B/La

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome

SS-A/Ro without SS-B/La

SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome

Jo-1

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis

RNP

Mixed connective tissue disease

Scl-70

Diffuse scleroderma

Anti-centromere

Limited scleroderma (CREST)

AUTOIMMUNITY AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM