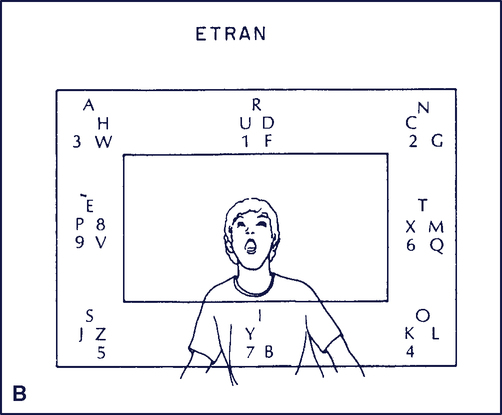

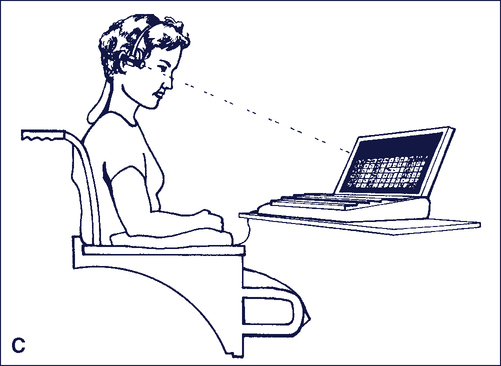

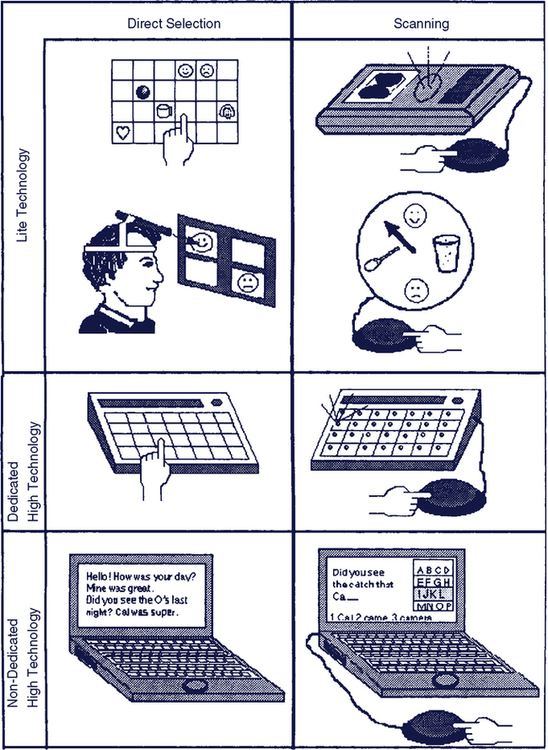

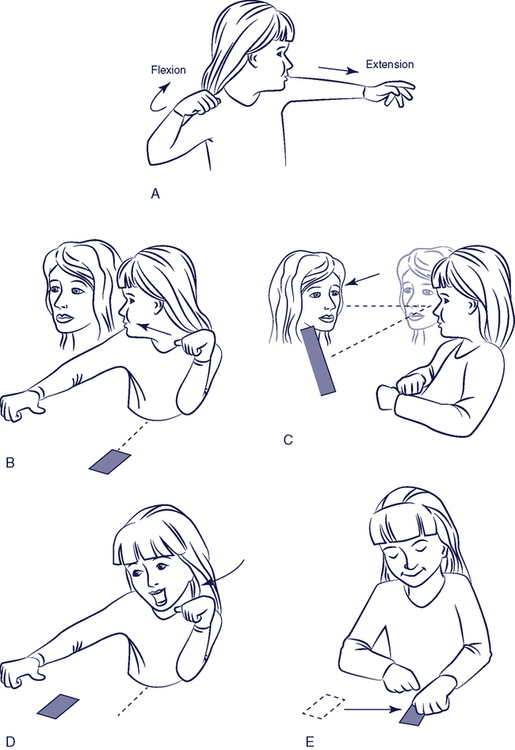

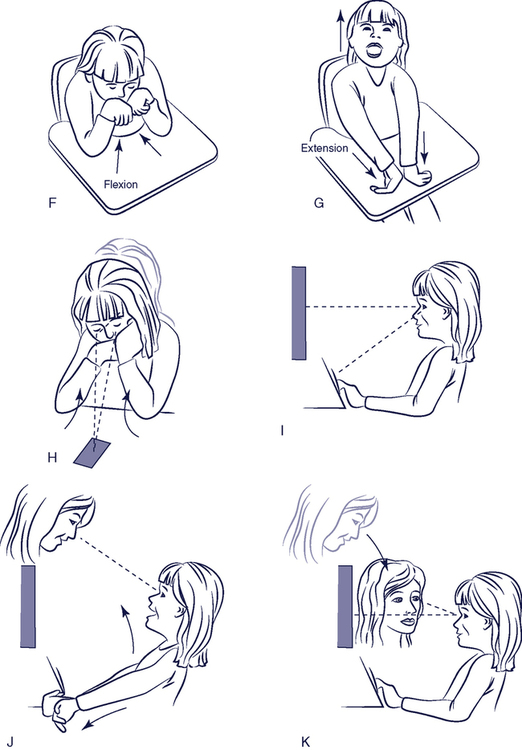

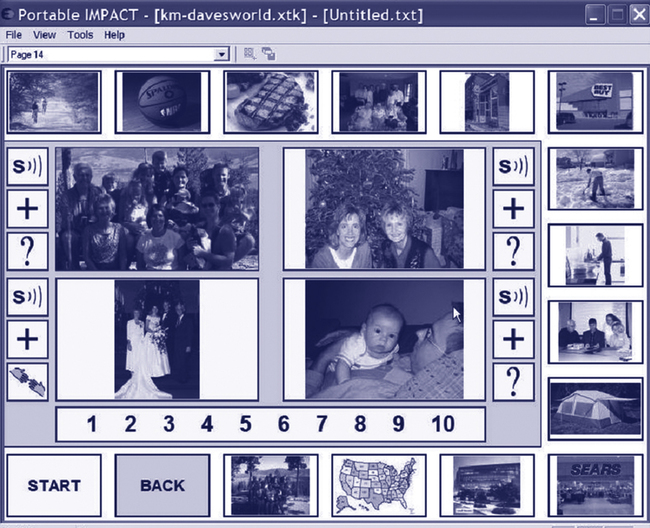

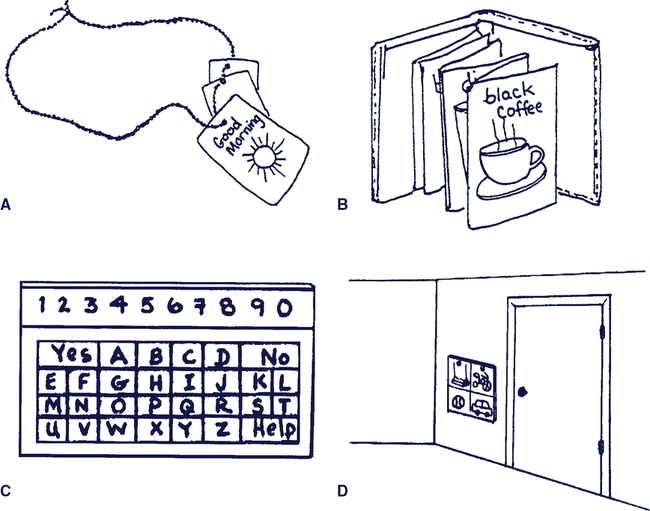

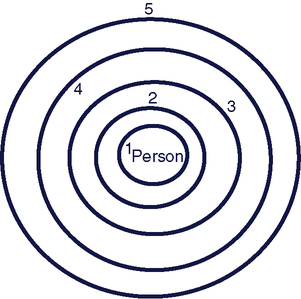

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Describe the different communicative needs of persons with disabilities 2. Discuss the basic approaches to meeting these differing needs 3. Describe the major characteristics of alternative and augmentative communication devices 4. Describe current approaches to speech output in assistive technologies 5. List and describe the major approaches to rate enhancement and vocabulary expansion 6. Discuss the major goals for, and the significance of, training in AAC device use and communicative competence 7. Describe the steps and procedures involved in implementing an augmentative and alternative communication device for an individual consumer Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is an area of clinical practice that deals with communication problems of people who have complex communication needs (CCN). These problems may occur at any point across the life span. Communication is the very essence of being human, and when someone is not developing speech and language skills, or has lost the ability to speak and/or understand spoken or written language, then AAC intervention approaches are required to meet their complex communication needs (CCN). People communicate differently with different partners, under different conditions, and by using a variety of tools, techniques, and strategies. AAC involves a wide range of techniques, strategies, and technologies to support the communication needs of individuals with CCN (see Figure 11-1). The focus of AAC must be on augmenting communication in ways the person values. Today, people with CCN are using AAC to attend schools and universities, work, carry on chats, participate in computer list serves and social networks, shop, order in restaurants, talk on the phone, and generally participate fully in society. People with CCN who have severe disabilities and who are able to obtain speech generating devices (SGDs) are living independently, getting married, and are active members of their communities. Individuals with CCN who do not gain access to AAC interventions may have limited social networks, have difficulty in reporting abuse, and be limited in their access to employment.21,25 There are many disabilities that can affect an individual’s communication skills and abilities. Communication disorders can be categorized into those that affect the production of sounds and intelligible speech and those that affect cognitive and language abilities. Some individuals cannot produce speech because of conditions present at birth or acquired later in life. For some, the problem is in making sounds, although many individuals can produce sounds without being able to produce speech. The production of sounds is called vocalization and it can be an effective way of communicating some things like yes and no, anger (screaming), happiness (laughing), sadness (crying), and getting attention. Even if sounds can be produced, an individual may have limitations that interfere with his ability to make sounds or control the muscles of the chest, diaphragm, mouth, tongue, and throat to produce intelligible speech. Dysarthria is a disorder of motor speech control resulting from central or peripheral nervous system damage that causes weakness, slowness, and a lack of coordination of the muscles necessary for speech production.1 Verbal apraxia is a disorder affecting the coordination of motor movements involved in producing speech caused by a central nervous system dysfunction.1 Written communication is also important and limb apraxia may impair the ability to write. When speech and/or writing are severely impaired, AAC approaches are indicated. Many individuals with disabilities affecting their communication benefit from AAC interventions. Developmental conditions such as cerebral palsy (CP), intellectual disabilities, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affect children and adults. Acquired conditions such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke/cerebral vascular accident (CVA), high-level spinal cord injury, and degenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), progressive aphasia, and multiple sclerosis can affect older children and adults. Estimates indicate that approximately 2 million people in the United States and from 0.3% to 1.0% of the total world population of school-aged children have a need for AAC.8 There are many ways of looking at augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems. Unaided communication or body-based modes describe communication behaviors that require only the person’s own body, such as pointing and other gestures, pantomime, facial expressions, eye gaze and manual signing, or finger spelling. These modes are often used together and may be combined with any available speech. A person’s disability affects interpretation of unaided modes of communication. For example, individuals with some physical disabilities have difficulty controlling facial muscles as well as their limbs. This lack of control can lead to unintended “communication” such as inadvertent smiling or unintended limb movements that could be interpreted as a meaningful gesture. When this happens, communication partners frequently misinterpret the nonverbal behaviors because eye gaze, facial expression, body movements, posture, traditional head nods, and pointing or reaching may be incongruent with the intended meaning or tone.41 Rush (1986)59 gives an example when he describes the difficulty his cerebral palsy causes him in delivering his line (a yell) in a play: “When a person with cerebral palsy wants to do something, he can’t and when he wants not to do something, he involuntarily does it. So getting my vocal cords to cooperate with the cue was as hard as memorizing a Shakespearean play [for a non-disabled person].” (p. 21) Gestures, facial expressions, and body movements help display emotional states, regulate and maintain a conversation, and support information exchange. Gestural codes (e.g., Amer-Ind* or Tadoma†) and formal manual sign systems (e.g., American Sign Language, Signing Exact English) are examples of more formal approaches.8 In Chapter 1 we defined low technology as inexpensive devices that are simple to make and easy to obtain. Many types of AAC approaches fit into this category. Examples of low technology approaches are shown in Figure 11-2. The communication cards shown in Figure 11-2, A, are on a chain worn around the neck of the person. The communication book shown in Figure 11-2, B, and the board or display shown in Figure 11-2, C, are based on letters/words/phrases or graphic symbols, respectively. The communication display in Figure 11-2, D, is an example of an activity-specific communication display that is placed by the door to facilitate the choosing of a recess activity. Other low-tech approaches, as described later in this chapter, may include placing symbols on items around a room to develop labeling skills, or using miniature objects as labels and formal systems such as the Picture Exchange System (PECS) to teach requesting. The term “high-technology AAC” refers to devices that have electronic components. Figure 11-3 illustrates some examples of high-tech AAC devices. There are two broad categories that are discussed in Chapter 5: direct selection and scanning. Some devices with limited functions are called “lite” technologies. The light pointer in Figure 11-3, C, is an example of a direct selection lite technology that has greater range and is easier to use than a mechanical head pointer. The lite technology devices in Figure 11-3, B and C, use scanning to choose between a few items using a single switch. “High technology” devices have many choices and typically provide speech output. They can use either direct selection (Figure 11-3, E) or scanning (Figure 11-3, F). Some AAC devices use mainstream technologies (e.g., computers and cell phones) with special software. These can use direct selection (Figure 11-3, G) or scanning (Figure 11-3, H). Finding the right AAC system for an individual requires a team approach. Each member of the AAC team has important roles and responsibilities: The client and family have the greatest knowledge of the daily communication needs of the person who has CCN. Family members are often the individual’s primary communication partners and serve as advocates and facilitators. The speech-language pathologist typically has the greatest general understanding of communication in general and can assess language and communication needs, abilities, and skills; select AAC materials and technologies; and develop a training program for the individual, caregivers, and family. The speech assistant may be responsible for programming the device with vocabulary for the individual and implementing the training program to teach the individual, family, and staff to use AAC system components effectively. The teacher sets educational goals and oversees classroom implementation of each child’s AAC system and has knowledge of literacy, social interaction, and education. The PT and/or OT carry out the motor evaluation, address seating and positioning needs, evaluate physical access to the AAC system, and have knowledge of how to support writing, drawing, and other activities of daily living. The positioning of the communication device for use (e.g., mounting to a wheelchair, locating on a table, or attaching it to the person for walking), the positioning of the control interface (see Chapter 6), and ensuring that the person is properly positioned to access the AAC system are often the responsibilities of a PT-assistant and OT assistant. In a classroom setting, an educational assistant may take on the roles of programming specific vocabulary into the device to meet educational goals and training the individual to use the device effectively for school work. In a work setting, programming and training may fall to a job coach. Family members may also be involved in programming and helping the individual learn to use the device effectively. These individuals support the person in the development of skill in using AAC to meet the person’s communication needs. They also may receive instruction that allows them to add vocabulary, set up the AAC system for daily use by the person, and take care of maintenance tasks such as charging batteries and cleaning the device. Key team members such as family, friends, co-workers, fellow students, residents living in the same group home, and employers are often referred to as “natural supports” because they have an ongoing relationship with the individual. Occasionally physicians, psychologists, vision specialists, and other professionals also play a role on AAC teams. First person accounts of AAC users provide an important perspective. Christopher Nolan,57 a man with cerebral palsy, wrote in the third person (as Joseph) about the importance of attentive and responsive communication partners. “Such were Joseph’s teachers and such was their imagination that the mute boy became constantly amazed at the almost telepathic degree of certainty with which they read his facial expression, eye movements, and body language. Many a good laugh was had by teacher and pupil as they deciphered his code. It was moments such as these that Joseph recognized the face of God in human form. It glimmered in their kindness to him, it glowed in their keenness, it hinted in their caring, indeed it caressed in their gaze.” (p.11) AAC systems can enhance interaction, but they can also become the center of attention, detracting from the real goal of interpersonal interaction, as William Rush59 noted: The loss of speech can also occur later in life. Doreen Joseph38 lost her speech following an accident. She described her situation: “I woke up one morning and I wasn’t me. There was somebody else in my bed. And all I had left was my head. Speech is the most important thing we have. It makes us a person and not a thing. No one should ever have to be a ‘thing.’” (p. 8) Sue Simpson64 lost her speech after a stroke at age 36. She wrote: “So you can’t talk, and it’s boring and frustrating and nobody quite understands how bad it really is. If you sit around and think about all the things you used to be able to do, that you can’t do now, you’ll be a miserable wreck and no one will want to hang around you for long.” (p. 11) Communication almost always involves a partner who may be in the room, on the phone, or a continent away on e-mail. Some “partners” may be merely imagined, as when someone writes a story. The “Circle of Communication Partners” (Figure 11-4) is helpful in defining the range of partners that a person with Complex Communication Needs who relies on AAC might encounter.13 The first circle represents the person’s life-long communication partners. This is primarily immediate family members. The second circle includes close friends (e.g., the people you tell your secrets to). These are often not family members. Acquaintances such as neighbors, schoolmates, co-workers, distant relatives such as aunts and cousins, the bus driver, and shopkeepers are included in the third circle. The fourth circle is used to represent paid workers such as a doctor, speech-language pathologist (SLP) or a physical therapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), occupational therapy assistant (OTA), physical therapy assistant (PTA), speech assistant, teacher, educational assistant, or babysitter. Finally, the fifth circle is used to represent those unfamiliar partners with whom the person has occasional interactions. This circle includes everyone who doesn’t fit in the first four circles. Table 11-1 shows that as we move from circle 1 to circle 5 the modes of communication required to communicate with people in each circle vary.17 For example, gestures and speech (even if it difficult to understand) are often preferred modes in circles 1 and 2. Circle 2 also includes some non-electronic communication boards as well as telephone and e-mail. Circle 4 reflects the school, work, and professional provider partners and therefore a wide range of modes are used. Circle 5 relies primarily on non-electronic communication boards, books, and SGDs of various types. Table 11-1 Each of the Circles in Figure 11-4 Has Different Partners and Modes of Communication *Blackstone SW and Hunt Berg M: Social networks: a communication inventory for individuals with complex communication needs and their communication partners – Inventory Booklet, Monterey, Calif.: Augmentative Communication, Inc., 2003. McCarthy and Light51 reviewed 13 research studies on partners’ attitudes toward individuals who rely on SGDs. They identified several factors affecting attitudes: (1) characteristics of typically developing individuals, (2) characteristics of the person using AAC, and (3) characteristics of the AAC system. These are elements of the social context of the HAAT model (see Chapter 2). Attitudes toward individuals who use AAC vary across the parameters of gender, type of disability, age, experience of the user of AAC, experience and familiarity with the disability and AAC by the partner, and social context. Attitudes appear to be formed by the interaction of many of these factors. Some of these attitudes are summarized in Box 11-1. Light (1988)43 describes four goals of communicative interaction: (1) expression of needs and wants, (2) information transfer, (3) social closeness, and (4) social etiquette. Expression of needs and wants allows people to make requests for objects or actions. Information transfer allows expression of ideas, discussion, and meaningful dialogue. Social closeness serves to connect individuals to each other, regardless of the content of the conversation. Social etiquette is used to describe those cultural formalities that are inherent in communication. For example, students will speak differently to their peers than to their teachers. Dowden and Cook (2002)28 defined three types of AAC communicators. Emergent communicators have no reliable method of symbolic expression and they are restricted to communicating about here and now concepts. Context-dependent communicators have reliable symbolic communication, but they are limited to specific contexts because they are either only intelligible to familiar partners, have insufficient vocabulary, or both. For example, a child may have symbols and understanding for specific school activities such as circle time or for interacting with their friends, but lack general vocabulary for going shopping or ordering at a restaurant or other typical activities of daily living. Independent communicators are able to communicate with unfamiliar and familiar partners on any topic. Each of these communicators has different needs and goals. Because the development of speech, language, and communication begins at birth, early intervention is important. Effective AAC interventions for children with developmental disabilities require that AAC be integrated into the child’s daily experiences and interactions, and that it take into account what we know about child development.48 For example, many young children do not have the physical or cognitive skills to learn to use current AAC selection techniques (e.g., scanning or encoding), and thus are unable to access some AAC systems. Also, the design of current hi-tech AAC technologies often requires a child to stop playing in order to use a communication device. A more desirable approach is to design AAC technologies and strategies that incorporate the use of AAC into the child’s play activities so the child can talk about her play or interact with peers while engaged in the activity. In short, to be effective the design, type, and layout of the AAC system components should match the desires, preferences, abilities, and skills of those who rely on AAC systems. This is often called “feature matching.” A major concern for parents is whether the use of AAC will impede their child’s development of speech. Research data puts all such fears to rest17. In fact, research has shown that the use of AAC does not interfere with speech development and may enhance the development or return of speech. There are a number of possible explanations for this, including increased acoustic feedback (from voice output SGD); increased experience with conversational turns and other communicative functions; reduced pressure to speak, which releases motor stress; and the development of an internal phonology due to AAC systems use.18 Research shows that children with a broad range of developmental disabilities can benefit from AAC interventions. Developmental disabilities include children with cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, Down syndrome, other genetic disorders, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cerebral palsy is a non-progressive motor impairment due to a lesion or anomalies of the brain arising in the early stages of its development.66 Cerebral palsy syndromes describe motor disorders characterized by impaired voluntary movement resulting from prenatal developmental abnormalities or perinatal or postnatal central nervous system (CNS) damage. It is primarily a disorder of muscle tone and postural control. Individuals who have cerebral palsy will often exhibit apraxia, which is the inability to perform motor activities even though sensory motor function is intact and the individual understands the requirements of the task.23 Primitive reflexes, characterized by immediate and automatic movement performed at a subconscious level, also accompany cerebral palsy.36 Typically these reflexes are inhibited or (more often) integrated into volitional movements in order to control posture and perform basic movement patterns as the infant develops. Cerebral palsy may affect the degree to which these reflexes are integrated and some reflex patterns persist into adulthood for those with CP. The primitive reflexes that most commonly influence AT use are the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) and the symmetrical tonic neck reflex (STNR). The impact of these on AAC use is shown in Figure 11-5.8 CP is also characterized by variation in muscle tone ranging from increased tone (referred to as hypertonicity or spasticity) to low tone (referred to as hypotonicity). In an individual child the tone may be mixed, may vary over the course of the day, or vary depending on the child’s position.66 This altered muscle tone has an impact on motor control required for the use of AAC devices. Oculomotor function is also abnormal (problems with eye movements) in many children with CP. Duckman (1979)29 found that 92% of the children with CP had oculomotor dysfunction of some type. This finding has direct bearing on tasks that require frequent redirection of gaze, such as looking at a keyboard to find the desired character and then looking at a display or screen to monitor the selections. As Scherer (1998)61 points out, the person who is born with cerebral palsy is likely to have adjusted to the disability and developed strategies that help accommodate for the lack of coordinated motor control. For example, some individuals are able to use a primitive reflex to initiate a movement. Others have learned to position equipment and materials in order to maximize the motor control they have. These individuals are inclined to view assistive technology as opening up new opportunities for them and they often apply their developed strategies to the control of these devices. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by significant social communication challenges throughout life that reflect impairments in social interaction and in verbal and non-verbal communication as well as restricted, repetitive, stereotypical patterns of behavior, interests, and activities.14 Early intervention (starting as young as two years) improves outcomes for children with ASD. These children often have difficulty with joint attention (i.e., coordinating attention between people and objects) and with understanding and using symbols. Approximately one-third to one-half of children with ASD do not use speech functionally.14 The learning styles of children with ASD show a strong preference for static information (e.g., visual information that doesn’t change). As a result, they often benefit from the use of “visual supports” (e.g., printed guides that provide cues such as a list of common phrases). Because speech and other elements of conversation are transient, AAC devices and communication displays that utilize static visual symbols provide possible assistance for the child with ASD. Also, because of their dependence on rote or episodic memory, children with ASD often benefit from contextual clues and prompts. However, this can lead to them becoming prompt or context dependent and can decrease the carryover of skills. Thus, AAC interventions that extend the use of language and appropriate communication behaviors across different contexts and partners are needed. Blackstone (2003)14 argues that AAC can be effective for children with ASD because it addresses both their unique learning styles and communication needs. Children with ASD can use no-tech (e.g., manual signs) and high- and low-technology approaches to AAC.54 At this time, there is no clear evidence that one approach is superior to any other. The use of total communication (speech and manual signing) provides advantages because there is no need to care for or operate a device and because it promotes more natural forms of communication. However, not all children (or their partners) do equally well with this approach. Some children develop more functional communication using low-tech–aided systems. The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)* is one widely used example. Voice-output communication aids can also support interactions. For example, Schlosser and Blischak (2001)62 suggested that electronically generated speech may be beneficial for children with ASD who have difficulty processing natural speech. Also, computer-aided instruction may help children with ASD attend to instructions and prompts when provided via electronic speech output. There are many considerations in choosing between the many available AAC approaches, including an individual’s preferences, ease of learning, effect on the development of speech and language, ability to use the approach functionally across partners, and the communication tasks the person needs to accomplish and contexts in which they take place. Finally, the degree of partner support and responsiveness is considered. Current best practices rely on clinician judgment as much as evidence because current research on the use of AAC approaches for individuals with ASD is promising, but inconclusive, in each of these areas. Adults with acquired disabilities such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), aphasia, and other static conditions may require the use of AAC interventions as part of the rehabilitation process.7 Persons with recovering conditions (e.g., traumatic brain injury or stroke) often experience changing levels of motor, sensory, and/or cognitive/linguistic capability. This group of users may benefit from the use of AAC to help them adapt. While many people may be unable to speak or write directly after a severe head injury or brain stem or cortical stroke, most will recover some abilities over a period of months or years. However, over the long-term, some individuals continue to benefit from the use of AAC if speech is unintelligible. In this section traumatic brain injury (TBI) and aphasia are discussed as examples of individuals with acquired AAC needs. TBI can result in the loss of speech and often causes physical, cognitive, and language impairments.6,46 The motor impairment is often severe in TBI and the sequelae include problems with cognition (thinking, memory, and reasoning); sensory processing (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell); communication (expression and understanding); and behavior or mental health (depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggression, acting out, and social inappropriateness). These factors frequently hamper function and often are long-term outcomes that effect communication and other functions in very subtle ways, limiting the ability to access AAC.22 While the long-term recovery of speech is variable, immediately following the injury many individuals benefit from AAC interventions to support functional communication. Beukelman et al. (2007)9 carried out a study of AAC use by individuals who had sustained a TBI. The individuals with TBI in this study generally accepted AAC recommendations, and none of the participants rejected AAC after receiving a low-tech or high-tech AAC option. When it did occur, AAC technology abandonment usually reflected the loss of a facilitator (a soft technology loss; see Chapter 1), not rejection of the technology (Box 11-2). Participants in this study relied predominantly on letter-by-letter spelling strategies primarily due to the interference of cognitive limitations with the ability to encode messages or utilize other message-formulation strategies. Beukelman et al. attempted to teach the use of encoding and/or word retrieval to several individuals with TBI who spelled their messages using AAC technology. Some were able to learn the encoding or prediction strategy in the intervention setting, but none used the strategy in their everyday communication, reporting that it was “too much work.” Persons who sustain a stroke often experience language difficulties that we collectively call aphasia. One lasting problem these individuals have is vocabulary retrieval or word-finding difficulties. There are several AAC-related approaches with potential for aphasia rehabilitation.37 For example, individuals who can recall first letters and recognize a desired word from a list may use word prediction devices or software. The individual begins typing a letter and then the device predicts several words from which to choose (see Figure 5-11). There are many factors that must be considered when applying AAC in aphasia rehabilitation. Research supporting aphasia intervention using AAC is described in Box 11-3. Some people with severe aphasia learn to augment their speech and communication efforts by relying on gestures and an alternative symbol system.37 However, while persons with aphasia may be able to use graphic symbols, many find it difficult to apply them socially or to generalize their use. =”p1295″>One commercial device designed specifically for persons with aphasia is the Lingraphica™, which organizes symbols by semantic categories (e.g., places, foods, and clothing) and includes synthetic speech output and animation of verbs (e.g., “walk” or “give”).* Lingraphica provides graphic building blocks which are called icons (small pictures, sometimes animated). The icons can be manipulated to generate messages using a cursor. Lingraphica also has applications that allow favorite icons, phrases, and videos selected on the Lingraphica to be transferred to the iPhone and iPod touch. The mobile accessory can be used as an AAC device for communication or for self-cueing and scaffolding (i.e., helping to generate expressive language by providing prompts). Other technological interventions for aphasia are focused on supporting specific communication tasks such as answering the phone, calling for help, ordering in restaurants or stores, giving speeches, saying prayers, or engaging in scripted conversations. These may be either paper-based systems or electronic devices. Portraits (static pictures or other symbols) contain limited, usually decontextualized information (e.g., a picture of a person with a plain background), and additional information about the person(s) or object in a portrait must be generated by the individual with aphasia or speculated on by the communication partner.9 This spontaneous generation of additional specific and detailed information is difficult for individuals with severe chronic aphasia. An alternative approach uses Visual Scene Displays (VSDs) (see Figure 11-6 and discussion later in this chapter). VSDs use personalized digital photos of scenes and arrange these on a dynamic display device (these devices are described later in this chapter). Each element in a visual scene is pictured in its natural relationship and position to all other elements in the scene.52 The meaning of all elements and semantic associations are integrally tied together, creating a holistic context. VSDs enable individuals with severe aphasia to use familiar photographs to engage partners in interactions about multiple topics. In addition, the design of the technology makes it relatively easy for partners to provide conversational supports such as prompting with familiar reminders. The individual with aphasia and the communication partner co-construct “the gist” of the visual scene. Contextualized pictures are paired with text and voice output to communicate specific messages, ask questions, and/or provide support for the communication partner. Because of the dynamic nature of the display, the user is continually prompted regarding the available choices, reducing the individual’s need to rely on recall memory. It is also possible to use the same approach with paper-based displays. There is a template provided by the University of Nebraska at http://aac.unl.edu/intervention.html. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also referred to as one of the motor neuron diseases, is a rapidly progressing neuromuscular disease that gradually reduces motor control until total paralysis results. It affects speech in the majority of cases (see Case Study 11-4). The spinal form of ALS affects one limb asymmetrically and spreads to other limbs and eventually to upper motor neurons and respiration.33 Speech is affected in the later stages. The bulbar form of ALS primarily affects the muscles of speech, swallowing, and respiration, resulting in loss of speech earlier in the course of the disease.33 While persons with ALS utilize the same AAC systems as others, there are unique factors considered during the intervention process. For example, it is not uncommon for someone to begin using a direct selection AAC system and later on require scanning due to loss of motor function. If this type of transition is not planned for initially by the interdisciplinary team, it can be very hard for the person to maintain effective interactions. However, it can be a very difficult topic for both the clinician and family to discuss. Families differ in their desire and ability to deal with the longer term implications of physical decline.11 Some families prefer to “plan ahead” and consider future needs while others prefer to take things as they come. Some Speech Generating Devices (SGDs) can accommodate direct selection and a variety of indirect selection modes, so these are often recommended. ALS patients tend to use high-tech aids with strangers for conversation.11 No-tech approaches, including “20 questions” (the person can answer yes or no by head nod, eye blink, or other means) or gestures may be most effective with family communication and to express basic needs. Because the no-tech approaches are only understood by family members, low-tech approaches such as letter boards are more often used with strangers. Individuals with ALS use their technology until within a few weeks of their deaths. In one study those with primary bulbar ALS used their AAC technology an average of 24.9 months, and those with spinal ALS used their AAC technology for an average of 31.1 months.52 This means that they will require support for AAC throughout the later stages of the disease. It is important that clinicians provide information regarding the speech-language characteristics of ALS at the outset of intervention. There is a relationship between speaking rate and intelligibility, with 80% intelligibility occurring at about 130 wpm.3 Speech rate continually drops as ALS progresses, and this measure is used to determine the timing of AAC interventions. It is recommended that individuals with ALS be referred for AAC assessment when their speaking rate reaches 100 to 125 words per minute on the Sentence Intelligibility Test (the mean speaking rate on this test for adults without disability is 190 words per minute).52 Families need to remain aware of AAC service intervention opportunities and the need for ongoing training. Flexible AAC devices and strategies that will accommodate for changes over the course of the disease are important. Acceptance of AAC by persons who have ALS is high. In one four-year study, over 96% of those given the choice of AAC accepted that choice.3 A key reason for acceptance of AAC by persons with ALS is their desire to continue interacting with communication partners in a variety of contexts. As the disease progresses it is increasingly important for the individual with ALS to have a reliable method to make their needs known. Establishing a reliable no-tech communication method, such as eye gaze or eye-blink yes or no, is important so that the individual retains some means of communication when all other motor functions are no longer available. Dementia is a syndrome, or pattern of clinical symptoms and signs, that can be defined by: (1) a decline of cognitive capacity with some effect on day-to-day functioning; (2) impairment in multiple areas of cognition (global); and (3) a normal level of consciousness.58 The incidence of dementia is expected to grow. Currently 10% of people aged 65 years and older and 47% of people 85 years and older have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.52 This percentage translates into about 4 million people in the United States, a number that is expected to increase to 14 million by the year 2050. A major characteristic of dementia is difficulty in communicating, both receptively and expressively. The aim of AAC intervention in dementia is to maximize communicative and memory functioning, to maintain (or increase) activities that increase participation/engagement, and maintain (or increase) quality of life for people with dementia across the disease progression.52 Successful AAC intervention may also increase the quality of life and decrease the stress of family and professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. AAC interventions for dementia are designed to maintain function, compensate for lost function, and/or counsel the individual or family regarding conditions and options for managing the symptoms of dementia. There are several forms of compensatory support typically used. Low-technology communication cards and books, pictures, drawings, and printed reminders can be designed to support those with dementia to remind them of temporal or semantic information. High-technology support such as computerized memory aids for visual or auditory information is also available (see Chapter 10). AAC in dementia intervention is typically designed to support the individual, rather than to support his or her communication interactions, per se.52

Augmentative and Alternative Communication

Disabilities affecting speech, language, and communication

What Is Augmentative and Alternative Communication?

Approaches to Alternative and Augmentative Communication

No-Tech AAC Approaches

Low-Tech AAC Systems

High-Tech AAC Systems

The AAC Team

The Importance of Augmentative Communication in the Lives of People with Complex Communication Needs (CCN)

Partners of People with CCN Who Rely on AAC

Circle

Partners

Commonly Used AAC Modes and Techniques*

1

Life-long communication partners, immediate family members

Facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations, speech, and manual signs

2

Close friends (i.e., people who you tell your secrets to), often not family member

Facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations, non-electronic communication boards and books, telephone, and e-mail

3

Acquaintances such as neighbors, schoolmates, co-workers, distant relatives (such as aunts and cousins), regular shop keeper or bus driver

Facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations, low-tech and high-tech dedicated SGDs, telephone, and e-mail

4

Paid workers such as a speech-language pathologist (SLP) or a PT, OT, OTA, PTA, speech assistant, teacher, teacher assistant, or babysitter

Facial expressions, gestures, vocalizations, manual signs, non-electronic communication boards and books, writing, low-tech and high-tech dedicated SGDs, and mainstream-based SGDs

5

Unfamiliar partners with whom the person has occasional interactions (e.g., a bus driver and seldom-visited or new shop keepers)

Facial expressions, gestures, non-electronic communication boards and books, low-tech and high-tech dedicated SGDs, and mainstream-based SGDs

Attitudes About and Acceptance of AAC

Communication needs that can be served by AAC

AAC for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Cerebral Palsy

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

AAC for Individuals with Acquired Disabilities

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Aphasia

AAC for Individuals with Progressive Neurological Conditions

ALS

Dementia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Augmentative and Alternative Communication