Asthma

Peyton A. Eggleston

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airways disorder that causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing. Usually, these episodes are associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is reversible either spontaneously or in response to treatment. The inflammation also causes an associated increase in the existing bronchial hyperresponsiveness to a variety of stimuli.

A leading cause of morbidity among children throughout the world, annually, asthma accounts for 3 million physician visits, 28 million restricted activity days, and one-third of all school days lost in the United States. In most urban hospitals, it is the most frequent cause for the hospitalization of children. In most Western countries, between 2% and 10% of children younger than age 16 are affected. In tropical and Third-World countries, the prevalence is significantly lower.

The prevalence of asthma in the United States has increased in children aged 5 to 14 years from 4.2% in 1980 to 8.7% in 2001. The reason for this increase is not clear, but it has been seen throughout the Western world and likely is related to increasing urbanization in these populations, increasing pollution, and more accurate diagnosis of asthma. Risk factors for increased prevalence and mortality in the United States

primarily include urbanization and poverty. Definite pockets of increased mortality are seen in cities, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups. Recently, it has been shown that children with frequent respiratory infections or with heavy exposure to bacterial products, such as endotoxin, have lower rates of asthma and atopy. This has led to a “hygiene hypothesis,” which proposes that early childhood infection modifies the immune response and reduces the tendency to produce IgE antibodies to environmental allergens.

primarily include urbanization and poverty. Definite pockets of increased mortality are seen in cities, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups. Recently, it has been shown that children with frequent respiratory infections or with heavy exposure to bacterial products, such as endotoxin, have lower rates of asthma and atopy. This has led to a “hygiene hypothesis,” which proposes that early childhood infection modifies the immune response and reduces the tendency to produce IgE antibodies to environmental allergens.

Deaths from asthma have been increasing steadily since the 1970s. The U.S. general population mortality rate due to asthma, 1.4 per 100,000, compares to 2.0 per 100,000 in Canada, 3.8 per 100,000 in Great Britain, 5.7 per 100,000 in Australia, and 6.0 per 100,000 in Sweden. At the same time, death from asthma is uncommon in children. In 2001, for example, the rate was 0.30 per 100,000 children for ages 5 to 14 in the United States, as compared to 11.6 per 100,000 for accidents in the same age group and 3.3 per 100,000 for cancer.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The median age of onset of asthma is 4 years; more than 20% of children develop symptoms within the first year of life. Risk factors for incident asthma include a personal or family history of atopy, especially multiple positive skin tests or radioallergosorbent tests (RAST). The association with parental smoking is weaker, but is consistent, especially if the mother smokes during pregnancy.

Respiratory infections, especially due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), increase the risk for persistent wheezing, and between 40% and 50% of children with RSV bronchiolitis develop chronic asthma.

In 60% of cases, asthma beginning in childhood resolves by young adult life. Fifty percent of those who undergo remission in adolescence become symptomatic again as young adults, and tests of airway hyperactivity show that, even in asymptomatic young adults, the airways have not returned to normal. In general, those in whom the disorder resolves have less severe, intermittent asthma; usually do not have multiple positive skin tests to inhalant allergens; and do not have persistent wheezing or rhonchi. Studies demonstrate that heavy exposure to pollution, allergens, or cigarette smoke makes resolution less likely.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

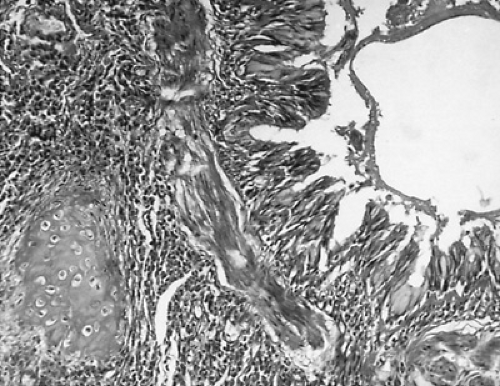

As shown in the pathologic specimen in Figure 420.1, asthma is an inflammatory disease. Characteristically, the infiltrate in the airway wall and the surrounding parenchyma is rich in eosinophils, but neutrophils, basophils, and mononuclear cells also are common, without organized lymphoid nodules or granulomas. Large areas of respiratory epithelium are desquamated, and collagen is deposited in the area of the basement membrane. Bronchial smooth muscle is hypertrophied and hyperplastic. Frequently, respiratory epithelium and inflammatory cells fill large mucus plugs in the airway lumen.

The best defined pathway leading to this pattern of inflammation is through mast-cell activation. Mast cells are fixed tissue cells activated by either lymphokines or IgE-dependent mechanisms; they produce a variety of proinflammatory substances. IgE-dependent inflammation is described in more detail in Chapter 419 but here we should note that activation leads to the rapid release of chemical mediators and rapid airway obstruction—the “immediate response.” This immediate response evolves into a late-phase reaction (LPR) within 2 to 4 hours after antigen exposure. In addition, an important physiologic element of asthma (i.e., airway hyperresponsiveness) has been found to increase for days to weeks after LPR.

FIGURE 420.1. Pathology of asthma. Hematoxylin-eosin–stained specimen of cross-section of a small bronchus of an asthmatic patient. |

It is important to recognize that all the classic airway pathology and bronchial hyperresponsiveness seen in asthma may occur without evidence of IgE-dependent sensitization. The mechanisms responsible for nonallergic or “intrinsic” asthma are not known.

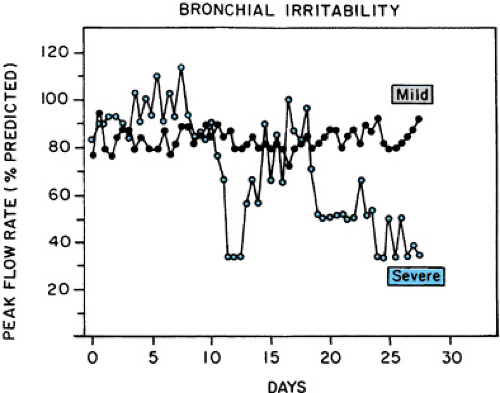

Airway Hyperresponsiveness

Highly variable airway obstruction is characteristic of asthma. This airway hyperresponsiveness is illustrated best in Figure 420.2, which shows the record of daily peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) measurements in two patients with asthma. With milder asthma, PEFR may be normal, but daily measures vary by more than 20%. With severe asthma, PEFR is frequently abnormal and daily variations are more than 60%. These variations in obstruction may be seen in response to many “precipitants” of bronchospasm, including exercise, irritants (cigarette smoke, odors, pollution, sulfite preservatives), weather changes, common colds, certain drugs (beta-adrenergic antagonists,

aspirin, and all nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents except acetaminophen). Allergens cause attacks when specific IgE antibody is present.

aspirin, and all nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents except acetaminophen). Allergens cause attacks when specific IgE antibody is present.

Airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness have been linked. Not only does bronchial hyperresponsiveness increase during the LPR, but allergen avoidance can decrease bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Allergic children who move to the Alps and adults who are confined to hospital experience a striking decrease in airway symptoms, medication requirements, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Clinical trials of home allergen avoidance also decrease bronchial hyperresponsiveness, but to a smaller extent.

PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR ASTHMA

Beta-Adrenergic Agonists

Beta-adrenergic agonists are the symptomatic therapy of choice, acting through specific airway receptors to reverse obstruction quickly; using short-acting agents, bronchodilation is maximal within 5 to 10 minutes. In addition to being effective bronchodilators, beta-adrenergic agonists inhibit immediate asthmatic responses to allergens, exercise, and many inhaled irritants when given just before exposure. They have little effect on the LPR or on the resulting increase in reactivity. Toxicity includes tachycardia, palpitations, and central nervous system excitement and muscular tremor. All are dose-dependent and rarely are a problem with appropriate inhalation dosing. Whenever possible, beta-adrenergic agonists should be inhaled, because effective bronchodilation can be achieved using doses 10 to 20 times lower than those using oral dosing. Nebulized drugs may be given in solution from a nebulizer, from a hand-held metered-dose inhaler, or from a dry-powder inhaler. Infants may be treated using a metered-dose inhaler using an AeroChamber and a face mask. Adolescents must be cautioned against overuse of the inhalers and over-reliance on its brief bronchodilatory effects.

Epinephrine, the first available beta agonist, still is prescribed but is no longer the treatment of choice. The current drug of choice is albuterol, which is beta2-selective and longer acting than epinephrine. Albuterol is a racemic mixture. Levalbuterol, the R-isomer of albuterol, became available recently and has the theoretical advantage of greater bronchodilation with fewer side effects. Clinical trials have shown few clinically relevant differences from the racemic preparation, however. Salmeterol, a beta2-selective agonist with a 12- to 18-hour duration of action, also is available. Because of its long duration of action, it may be considered a disease-controlling medication, but should only be used as a controller in combination with inhaled corticosteroids. A dry-powder device is available that combines salmeterol and fluticasone. Published evidence from many sources demonstrates that the preventive effect of beta-adrenergic agonists diminishes with prolonged use and that excessive use may be associated with increased hospitalizations and mortality. The role of these drugs appears to be limited to controlling symptoms, and they should not be used as the only chronic therapy except in mild, episodic asthma.

Cholinergic Antagonists

Anticholinergic drugs are useful bronchodilators in acute asthma but are not effective when used chronically. In acute asthma, they have been shown to act synergistically with beta adrenergic agonists. They are much less effective than beta-adrenergic agonists in the chronic management of asthma, and toxic effects (xerostomia, mydriasis, tachycardia, and abdominal pain) are annoying. Representative compounds in clinical use include atropine and ipratropium.

Cromolyn

Cromolyn was the first drug without bronchodilator properties shown to prevent allergen-induced asthma in humans. It is the only available drug that effectively inhibits both early- and late-phase asthma caused by allergen exposure. In chronic use, it reduces airway hyperreactivity slightly, and disease activity is decreased. Compared with other medications that control asthma, it is much less effective. Except for a rare allergic reaction, cromolyn is nontoxic.

Theophylline

Theophylline is a weak bronchodilator with antiinflammatory properties comparable to cromolyn; the mechanism for either of these effects is not known. Toxic effects include both mild symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, irritability) and severe and life-threatening reactions (intractable convulsions, tachyarrhythmia). Both therapeutic and toxic effects are dose dependent, and it is difficult to maintain therapeutic effects without some toxicity. The drug was once the only orally effective agent; now it is used as a supplemental drug for chronic asthma in severe cases.

Leukotriene Modifiers

Leukotrienes, released from mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils, are potent bronchoconstrictors and pro-inflammatory mediators. The leukotriene modifiers act either to decrease the production of inflammatory agents or to inhibit tissue effects to those agents. The most useful clinical agents, montelukast and zafirlukast, are competitive inhibitors that have been shown to decrease airflow obstruction in mild asthma within an hour of dosing and to be effective as antiinflammatory agents. Chronically, they decrease bronchial hyperresponsiveness and inhibit bronchoconstriction from exercise and allergen exposure. Beta-adrenergic agents are more effective bronchodilators, and inhaled corticosteroids are more effective in chronic persistent asthma in clinical trials, but the low toxicity of the leukotriene modifiers and their effectiveness when taken orally has allowed them to become widely used alternatives for the daily therapy of mild persistent asthma. They also have been shown to increase the chronic benefits of inhaled corticosteroids.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the most effective therapy available for the acute and chronic treatment of asthma. They have broad antiinflammatory effects on most inflammatory cells and are capable both of reversing acute exacerbations of asthma and reducing bronchial hyperresponsiveness when used chronically, so that airway response to many triggers such as exercise, allergen (late phase), and irritants are reduced. For chronic use, inhaled corticosteroids are an important new advance in asthma therapy. By modifying the glucocorticoid molecule, these compounds have been rendered approximately 100 times more potent than prednisone. In addition, they are absorbed poorly from the respiratory tract and are cleared rapidly when absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. These pharmacokinetic properties provide a wide therapeutic ratio, leading to the current recommendation that they be used as first-line therapy for persistent

asthma of any severity. Available agents and their dose ranges are listed in Table 420.1.

asthma of any severity. Available agents and their dose ranges are listed in Table 420.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree