Chapter 10

Assistive Technologies to Aid Cognitive Function

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

1. Apply the HAAT model to help identify appropriate assistive technologies for individuals with cognitive disabilities

2. Identify cognitive skills that underlie functional performance for persons with cognitive disabilities

3. Understand what cognitive faculties are commonly compromised in specific disorders

4. Understand the role of assistive technologies in aiding cognitive function

5. Identify and describe some of the assistive technologies that are currently available to assist individuals with cognitive impairments

“Cognition is the mental process of knowing, including aspects such as awareness, perception, reasoning, and judgment.”* Cognitive is the adjective referring to cognition. Cognitive disabilities may be present at birth or result from injury or disease. Of those present at birth, some are genetically transmitted, others result from prenatal or perinatal conditions, and there is no identifiable cause for many other cases. Acquired cognitive disabilities are the result of injury or disease. Needs that result from cognitive disabilities include memory loss, dementia, language disorders, the inability to make decisions, and the incapacity to function independently. For any individual with a particular cognitive disability, existing skills and possible limitations can be identified.

There are over 20 million individuals with a cognitive disability in the United States.7 This number can be broken down into categories: mental illness: 27%; Alzheimer’s disease: 20%; brain injury: 27%; mental retardation/developmental disabilities: 22%; and stroke: 4%.

The HAAT model (see Chapter 2) consists of four elements: Human, Activity, Context, and Assistive Technology (Figure 2-1). In this chapter we focus on human cognitive skills and activities that require those skills. For example, the activity might be carrying out a sequence of steps, such as for making a bed in the context of the home. Alternatively, as shown in Figure 10-1, the context might be the broader community, where devices that provide assistance for independent navigation are important. When we know the activity and the context we can determine the required set of skills to accomplish the activity. If there is a gap between the abilities required to complete the task and the individual’s skills, we can look for assistive technologies that can aid or replace the required skill. The expected skills and limitations presented in this chapter are general and every individual is unique. The case study “Intellectual Disability and the Tasks of Daily Living” illustrates how assistive technologies can be identified and applied to meet cognitive needs.

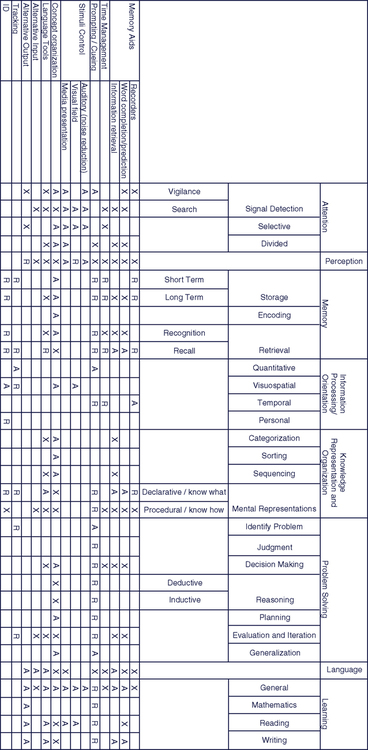

Cognitive skills

Understanding the cognitive demands of various tasks can help us understand why an individual may find a seemingly simple task to be very difficult, while a seemingly difficult task may be carried out virtually effortlessly. Some cognitive skills such as memory, attention, information processing, and problem solving are better understood than others.43 The definitions of some of the cognitive skills for which assistive technologies have been developed are listed in Box 10-1. Each skill listed will be described briefly in this section; for more detailed descriptions, refer to a cognitive psychology textbook.43

Perception

Perception is the interpretation of sensory information received through our eyes, ears, and skin, i.e., what we see, hear, and feel.2 Perception is a very basic cognitive skill that is integrated with higher-order cognition to achieve various skills, such as sequencing the steps required to make a bed. Impairments that affect perception limit an individual’s ability to use information from the environment to assist her daily activities. For example, someone with reduced visual acuity may have difficulty perceiving text that is presented on a computer screen. In this case, enlarged letters and auditory feedback may aid her when using a computer for word processing.

Attention

Attention is the ability to focus on a particular task.50 For example, selective attention refers to the ability to shift attention between competing tasks, which requires selectively attending to one stimulus while ignoring another.21 The characterization of different types of attention provides insight into different areas in which people may have strengths and weaknesses and for which assistive technologies may be able to help.

Using selective attention, we filter out distractions and focus on the event we have chosen.3 Variability in our selective attention skills is common, especially when there are distractions. For some individuals, the influence of distractions is such that they are unable to focus on a task when another stimulus (e.g., a conversation) is occurring in the background. For example, individuals with attention deficit disorder have difficulty focusing on the teacher in class. There are other situations in which we are required to devote attention to two or more tasks at the same time using divided attention. One example is listening to a lecture and taking notes. Students need auditory attention and processing skills to understand what the teacher is saying, and additionally require visual and tactile skills to take notes. While the activities of listening to a lecture and taking notes appear to be concurrent, in fact attention is moving quickly between the two tasks.

Memory

Two common ways of retrieving information from memory are recall and recognition. Free recall tasks provide virtually no hints at all, while cued recall tasks add in a small amount of information about the material the participant is supposed to recall.50 Recognition tasks provide the target (material to be remembered) along with other material meant to distract the person; for example, recognition is often involved in multiple choice questions.

Orientation

Our awareness of our own identity and that of others in our environment is called orientation to person.49 Orientation to person is commonly affected in disorders such as dementia and traumatic brain injury (TBI), where people forget not only who others are, but also who they are. A simple assistive technology that can aid orientation for a person is a card that lists the person’s address and phone number, which can be presented to a passerby if they become lost.

We are constantly made aware of where we are and where we are going by paying attention to clues such as streets and landmarks, or by knowing that home lies east of where we are. More importantly, the ability to guide ourselves from point A to point B using these clues is called orientation to place.49 Assistive technology way-finding devices can aid people who have orientation-to-place limitations.

Orientation to time is what permits us to know it is lunch time and that we can go on our daily walk.49 For individuals who have difficulty reading standard clocks, there are assistive technologies that provide a sense of when events are to occur and the amount of time that must elapse before the event occurs. Orientation to time is broader than simply the time of day; often the question for an individual is “What day is it?” It also involves orientation to things such as time of year (e.g., certain holidays, which are cues for behaviors and activities).

Problem Solving

Problem solving is the process of working through details of a problem to reach a solution. In the hierarchy of Box 10-1, the first step in problem solving is identification of the problem. If a person has difficulty identifying problems, various devices such as ones that prompt or cue may help.* Judgment is the ability to make sound decisions and recognize the consequences of decisions taken or actions performed. Decision making is the cognitive process of selecting a course of action from defined alternatives. Two types of reasoning are deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is a process by which an individual tries to draw a logically certain and specific conclusion from a set of general propositions. For example, when using an assistive device that requires touching a screen location (a button) to create an action, the statements “All buttons make something happen when you push them” and “This is a button” lead to the conclusion, “Something will happen if this button is pushed.” Inductive reasoning is a process by which an individual tries to reach a probable general conclusion based on a set of specific facts or observations. This conclusion is likely to be true, based on past experience, but there is no guarantee that it will absolutely be true.26 In assistive technology design the existence of various types of reasoning implies that the steps required for operation of a device must be logical and intuitive from the user’s point of view, not just from the designer’s point of view. For example, a navigational aid designed for someone with intellectual disabilities needs to present information via voice in simple direct commands (e.g., “go to the white building”) rather than in more abstract general terms (e.g., “turn right 45 degrees and walk 20 meters, then turn right 30 degrees”).

Once a problem solution has been derived, the next step in problem solving involves confirming the successful conclusion of the task. The problem solver must evaluate the outcome of his or her actions and determine whether the task has ended successfully, or whether it requires continuation or repetition (called iteration). Generalization is the carry-over of knowledge or skills from one kind of task or one particular context to another kind of task or another context. Knowledge is most likely to be generalized when the conditions under which the knowledge is to be used are very similar to those under which the knowledge was acquired.26

Language and Learning

Language is fundamental to cognitive task representation. Through language and the process of exchanging information, we can express our thoughts, needs, and ideas. Language is a method of communication and is composed of rules (grammar) and symbols, expressed by gestures, sounds, or writing. When teaching a skill or task, language is used to portray the desired outcome. Learning is the process by which knowledge, skills or attitudes are acquired and it can be attained through study, experience or teaching. In Figure 10-1 we have placed learning at the end of the hierarchy because we believe it builds upon the previously mentioned skills, like building blocks. General learning refers to the basic ability to acquire the knowledge, skills, or attitudes that are necessary for the more specific types of learning: mathematics, reading, and writing. The ability of someone to learn and comprehend in each of these categories helps define both the features the assistive technology must have as well as the skills the person needs in order to use it. Examples of AT for learning are discussed in Chapters 11.

Disorders that may benefit from cognitive assistive technologies

Cognitive skills may be compromised as a consequence of a number of disorders. Congenital disorders (those present at birth) include intellectual or developmental disabilities (DD), learning disabilities (LD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Acquired disorders that can lead to cognitive limitations include dementia, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and cerebral vascular accidents (CVA). The characteristics of these disorders are summarized in Table 10-1.

Table 10-1

Disorders That May Benefit From Cognitive Assistive Technologies

| Disorder | Incidence | Characteristics |

| Intellectual disability | 8 individuals per 1000 (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/ mmwrhtml/00040023.htm) | Limitations in functional skills; impairments in memory, language use, communication, abstract conceptualization, generalization, and problem identification/problem solving47 |

| Learning disability | 2% of children | Significant difficulties in understanding or in using either spoken or written language; evident in problems with reading, writing, mathematical manipulation, listening, spelling, or speaking19 |

| ADHD | 4%12 and 5% to 7% (www.adhd.com) | Typical capacity to learn and to use their skills confounded by factors that make it difficult to fully realize that potential; easily frustrated, have trouble paying attention, prone to daydreaming and moodiness; fidgety, disorganized, impulsive, disruptive, or aggressive42 (www .adhdcanada.com) |

| ASD | 1 child per 165, 25% exhibit intellectual disability, 4 times more prevalent in boys than girls6 | Varying degrees of impairment in communication and social interaction skills or presence of restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior |

| Dementia | 0.5% to 1% (<65 years), 7% to 10% (65 to 75 years), 18% to 20% (75 to 85 years), 35% to 40% (>85 years) | (1) Decline of cognitive capacity with some effect on day-to- day functioning, (2) impairment in multiple areas of cognition (global), and (3) normal level of consciousness39 |

| TBI | Mild: 131 per 100,000 Moderate: 15 per 100,000 Severe: 14 per 100,000 people (21 per 100,000 if prehospital deaths included)17 | See Table 10-6 |

| CVA | 160 per 100,000 (overall), 1000 per 100,000 (age 50 to 65 years), 3000 per 100,000 (>80 years)18 | Visual neglect, apraxia, aphasia, dysphagia, perceptual deficits, impaired alertness, attention disorders, memory disorders, impaired executive function, impaired judgment, impaired activities of daily living38 |

Congenital Disabilities

Intellectual Disabilities

Intellectual disability is typically defined as a disability where one has a below-average score on an intelligence or mental ability test as well as a limitation in functional skills.47 These functional skills include (but are not limited to) communication, self-care, and social interaction. The terms developmental disability, cognitive disability, and mental retardation are often used to describe individuals with intellectual disabilities. Intellectual disability can range in severity from mild to severe.

Learning Disabilities

Learning disabilities (LD) are disorders in which one has near-normal mental abilities in general, but a deficit in the comprehension or use of spoken or written language. These disabilities may be manifested as a significant difficulty with reading, writing, reasoning, and/or mathematical ability. Because students with learning disabilities tend to perform poorly on standardized tests, it was long thought that learning disabilities were a mild form of intellectual disability. This assumption is untrue; learning disabilities can be thought of as a deficit in the processing and integration of information in an area (e.g., reading) as opposed to limitations in the basic ability in that specific area of learning. People with LD have typical age-related capacity in all areas. Table 10-2 lists abilities associated with learning disabilities. However, processing deficits lead to the problems in learning identified above.27

Table 10-2

Categorization of Abilities Associated with Learning Disabilities

| Explicit Abilities | Implicit Abilities |

| Reading skills (dyslexia) | Visual or auditory discrimination |

| Mathematical skills (dyscalculia) | Visual or auditory closure |

| Writing skills (dyslexia, dysgraphia) | Visual or auditory figure-ground discrimination |

| Language skills (dysphasia) | Visual or auditory memory |

| Motor-learning skills (dyspraxia) | Visual or auditory sequencing |

| Social skills | Auditory association and comprehension |

| Spatial perception | |

| Temporal perception |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is defined as a pattern of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity that is more frequent or severe than for typical people of a given age (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/complete-index.shtml). The delay aversion hypothesis of ADHD posits that the ADHD child distracts himself from the passing of time when he is not in control, which explains daydreaming, inattention, and fidgeting.41 Children (and adults) with ADHD have a normal capacity to learn and to utilize their skills, but suffer from confounding factors that make it difficult to fully realize that potential.41 Particularly, those with ADHD can be easily frustrated; have trouble paying attention; are prone to daydreaming and moodiness; and are fidgety, disorganized, impulsive, disruptive, and/or aggressive (www .adhdcanada.com).

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder that is characterized by varying degrees of impairment in communication and social interaction skills, or the presence of restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior. A commonly used definition for autism is that of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),1 which classifies autism as a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). As the term implies, this disorder covers a wide spectrum of conditions, with individual differences in the number and kinds of symptoms, levels of severity, age of onset, and limitations with social interaction. Major subtypes of ASD include Autistic Disorder, Asperger Syndrome, Rett Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorders, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

Acquired Disabilities

Dementia

The word dementia comes from the Latin de mens which means “from the mind.” Dementia is best defined as a syndrome, or a pattern of clinical symptoms and signs, which can be defined by the following three points: (1) a decline of cognitive capacity with some effect on day-to-day functioning; (2) impairment in multiple areas of cognition (global); and (3) a normal level of consciousness.39 Dementia is distinguished from congenital cognitive disorders (such as intellectual disability, learning disabilities, etc.) by its age of onset and its degenerative component. It is also important to note that although it affects multiple areas of cognition, not all areas are affected.

Rabins, Lyketsos, and Steele (2006)39 define the “Three pillars of dementia care.” The first is to treat the disease, which helps identify current needs as well as future necessities as the disorder progresses. The second is treatment of the symptoms. By treating the symptoms, the patient’s quality of life will improve in the cognitive, functional, and behavioral domains. Medications and technology are the two main ways to accomplish this task. Third, patient support is important and leads to ensuring that the patient’s needs are met and the quality of life is improved as much as possible.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

People who experience a traumatic brain injury (TBI) often lose significant cognitive function. A TBI may occur when the head or brain is struck by an external force, such as from a fall, a gunshot wound, or a motor vehicle accident (Table 10-3). The extent of the trauma to the brain, and not the injury itself, is the determining factor in diagnosing TBI. For instance, it is possible to incur TBI as the result of both open-head injuries (the brain is exposed to air) and closed-head injuries (no brain exposure). The effect of a TBI on an individual’s cognitive ability varies from case to case, in terms of both severity and the set of skills affected.

Table 10-3

Data on Causes of Traumatic Brain Injury (Injury Control Research Center)

| Cause | Percentage of Total |

| Motor vehicle crashes | 64% |

| Gunshot wounds | 13% |

| Falls | 11% |

| Assault | 8% |

| Pedestrian | 3% |

| Sports | 1% |

Data from TBI Inform, June, 2000. Published by the UAB-TBIMS, Birmingham, AL. © 2000 Board of Trustees, University of Alabama, http://main.uab.edu/tbi/show.asp?durki=27492&site=2988&return=57898#cause.

Not all head injuries give rise to TBI, and there is an accepted scale for diagnosing such an injury. One tool available to assist with diagnosis is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), a rating system used for describing the severity of a coma.17 The Glasgow Coma Scale ranks comas on a scale of from 3 (most severe) to 15 (mildest) in the eye response, verbal response, and motor response categories. A score on the GCS of 12 or higher is a mild brain injury, and below 8 is considered a severe injury.17

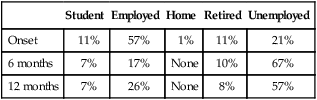

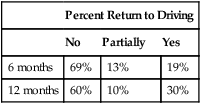

If the GCS does not indicate TBI, one of the following two criteria must be satisfied for a TBI diagnosis: either the patient has amnesia from the traumatic event, or the patient has a documented loss of consciousness. It is common to have a recovery period following the injury. This recovery usually plateaus within 12 months post-injury, and the extent of recovery is both variable and unpredictable.9 A good measure of the extent of a TBI patient’s recovery is his or her return to the preinjury activities of daily living. Two main recovery indicators are the return to work and the return to driving, both important tasks for independent living. Data on returning to work are summarized in Table 10-4, and similar data for returning to driving are shown in Table 10-5.37 In both cases, very little improvement was observed beyond 12 months post-injury.

Table 10-4

| Student | Employed | Home | Retired | Unemployed | |

| Onset | 11% | 57% | 1% | 11% | 21% |

| 6 months | 7% | 17% | None | 10% | 67% |

| 12 months | 7% | 26% | None | 8% | 57% |

Data from IRCR Study, 1999, http://www.neuroskills.com/whattoexpect.shtml.

Table 10-5

| Percent Return to Driving | |||

| No | Partially | Yes | |

| 6 months | 69% | 13% | 19% |

| 12 months | 60% | 10% | 30% |

Data from ICRC study, 1999, http://www.neuroskills.com/whattoexpect.shtml.

Typical cognitive and behavioral difficulties that a person with TBI may encounter are listed in Table 10-6.37,40 Two areas of importance are memory and language skills, as these may benefit from intervention with assistive technology.

Table 10-6

List of Typical Cognitive and Behavioral Difficulties after TBI

| Type of Difficulty | Examples |

| Cognitive | Processing of visual or auditory information |

| Disrupted attention and concentration | |

| Language problems (i.e., aphasia) | |

| Difficulty storing and retrieving new memories | |

| Poor reasoning, judgment, and problem solving skills | |

| Difficulty learning new information | |

| Behavioral | Restlessness and agitation |

| Emotional lability and irritability | |

| Confabulation | |

| Diminished insight | |

| Socially inappropriate behavior | |

| Poor initiation | |

| Lack of emotional response | |

| Projecting blame on others | |

| Depression | |

| Anxiety |

Stroke

A stroke, or cerebral vascular accident (CVA), is an incidence of irregular blood flow within the brain causing an interruption in brain function. A stroke may arise from a lack of blood flow to the brain (known as an ischemic stroke) or from ruptured blood vessels in the brain (a hemorrhagic stroke).25 The neurological damage incurred as the result of a stroke produces symptoms that directly correspond to the injured area within the brain.38 A CVA causes acute damage to the brain; there are no degenerative effects after the onset of injury. As with TBI, persons who have sustained a stroke often have a recovery period where portions of the brain learn to compensate for damaged areas. Typical cognitive and behavioral difficulties associated with stroke are shown in Table 10-7. Most recovery (as observed by the return to activities of daily living) occurs within 6 months after onset.8 The majority of persons with CVA are able to return home following their initial hospitalization period. A summary of discharge locations following hospitalization for stroke is shown in Table 10-8. These data suggest that the number of people returning home following a CVA is increasing, which might be attributed to improvements to hospital care at the onset of stroke. Children may have a more pronounced recovery than adults, as their brains have a greater degree of plasticity. Also, women may display greater recovery of lost language skill than men, as the language centers of the brain are larger in women than in men.8

Table 10-7

List of Typical Cognitive and Behavioral Difficulties after Stroke

| Type of Difficulty | Examples |

| Cognitive | Visual neglect, hemianopsia |

| Apraxia | |

| Language problems (i.e., aphasia, dysarthria) | |

| Perceptual deficits (i.e., figure-ground impairment, disorientation) | |

| Impaired alertness, attention disorders | |

| Memory problems, both short-term and long-term | |

| Perseveration | |

| Decreased executive function | |

| Behavioral | Impaired judgment |

| Impulsiveness | |

| Emotional lability | |

| Confabulation | |

| Poor initiation | |

| Mood alterations | |

| Depression |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree