Clinical assessment is an integral component of case conceptualisation and treatment planning. While the assessment of symptoms is a major component of any clinical investigation, the assessment of other related conditions such as cognitive impairment and substance misuse should also be considered when determining treatment options for people such as Sam. It is clear that the level of distress experienced due to symptoms will influence the location of treatment (inpatient versus outpatient), the nature and approach to treatment (psychotherapy, medication or both), the level of clinical expertise required to provide the treatment, and the need for other support services such as accommodation, employment or training. Moreover, monitoring symptom levels is useful since a good outcome for many people with severe psychiatric disability is likely to be a reduction in the frequency, duration or severity of symptoms, rather than a complete cure.

Ongoing assessment and monitoring of symptoms and related domains is essential to key decisions such as titrating the degree of support required, providing early intervention to avert relapse, timing new initiatives such as a new job, and negotiating continuance or termination of an intervention. In the absence of adequate monitoring, it can also be difficult to know whether progress is being achieved, especially when it is slow or variable.

In this chapter, we identify a subset of measures that could be used in clinical practice to assess severity of psychotic symptoms, depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and cognitive impairment in people with psychiatric disability.

Symptom rating scales

The use of rating scales to assess changes in symptoms increased from the early 1960s, with the need to assess response to emerging psychotropic medications. For example, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was introduced in the early 1960s to assess the effectiveness of chlorpromazine (Overall & Gorham, 1962). At the same time, measures of depression and anxiety, such as those developed by Hamilton, emerged to assess the effectiveness of the new antidepressant medications that were gaining popularity at that time (Hamilton, 1960). While these measures are still widely used, a range of more specific measures has been introduced to assess symptoms in different client groups (adolescents/elderly) and in clinical subgroups such as those with schizophrenia (e.g. the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia).

Measures described in this chapter

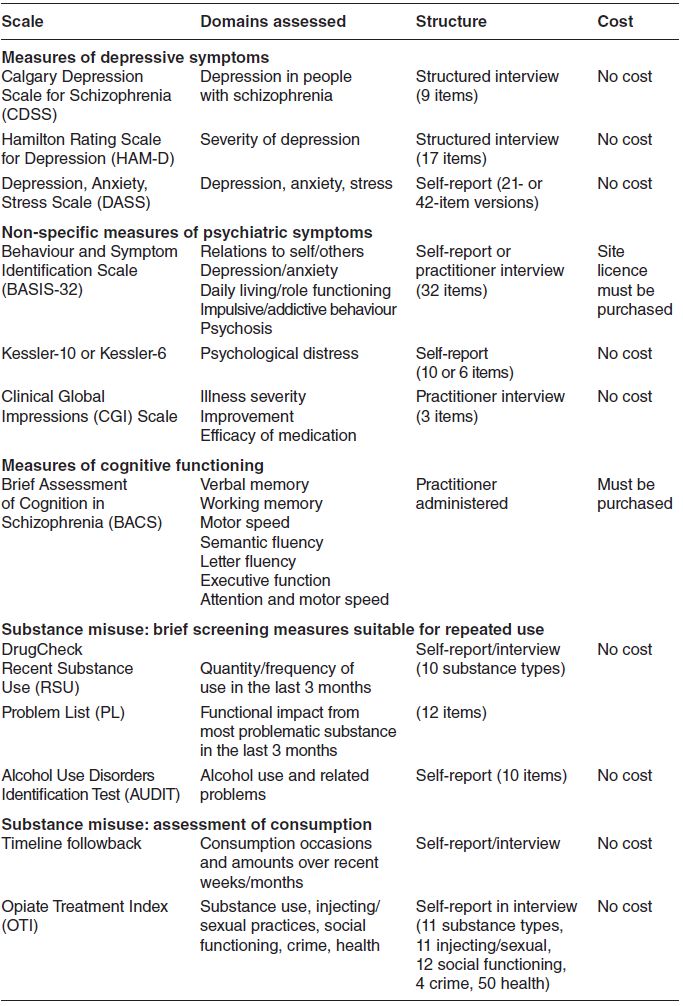

While a broad range of symptom measures currently exists, many are too lengthy, cumbersome and time consuming to be completed routinely by rehabilitation staff. Most of these are more suitable for research and evaluation purposes (e.g. where they may be completed every few months) rather than in clinical practice (where it may be necessary to have measures completed every 1–4 weeks). Therefore, we focus on some of the more clinically useful measures available Table 2.1). These scales reach a compromise between the burden on the clients and practitioners to complete the measures and the quality of the data they provide. For example, while the BPRS (mentioned above) is a well-recognised measure of symptoms, it is not included here due to the considerable training that is required.

A short description of each measure is provided with an example of its structure. Some of the measures are provided in full (where copyright restrictions allow).

Self-report versus practitioner-rated measures

Approaches to the assessment of symptoms have been developed in two broad formats: (i) self-report measures (completed by the client) and (ii) those administered through interview with a practitioner (practitioner rated). Self-report measures (e.g. Kessler-10) offer some advantages over practitioner-rated measures: they generally take less time to administer and do not require extensive training in their use, making them less expensive to employ. In addition, the information being collected is obtained directly (i.e. without rater interpretation) from the individual being assessed. This is particularly important when collecting client perceptions or subjective experiences (such as in assessments of quality of life and satisfaction). However, self-rating scales do require that clients are able to read and be well enough to understand what is being asked of them. While some self-report measures can validly be administered in an interview format, most have not undergone checking to establish that this is the case, and care needs to be taken to avoid paraphrasing of questions (which may alter their meaning).

Table 2.1 Summary of measures.

People with severe mental illness may not always be able to appraise their own behaviour or performance because of cognitive impairment, or may be unwilling to disclose personal failings, especially if they do not feel it is safe to do so (e.g. if discharge or new opportunities are believed to rest on non-disclosure). The establishment of trust is even more critical than in other contexts and observation or collateral reports may often be necessary to supplement self-reports. While interviews also rely extensively on self-report, they do provide opportunities for observation of behaviour and checking internal consistency of answers.

Assessment of depression

Depression can affect emotions, motor function, thoughts, daily routines such as eating and sleeping, work, behaviour, cognition, libido and overall general functioning. While some scales have attempted to consider all these domains, others have tended to be less inclusive and focus on the main symptoms of depressive illness. More recently, there has been a tendency to develop scales with specific populations in mind (e.g. The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia).

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) was specifically designed to assess depression in people with schizophrenia. Unlike some of the other depression measures available, the CDSS includes an assessment of suicidal thoughts (Item 8) and hopelessness (Item 2). This is an important feature of the CDSS since those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are at higher risk for suicide (Cadwell & Gottesman, 1990). Moreover, weight changes are not assessed as weight gain/loss can be related to the use of psychotropic medications.

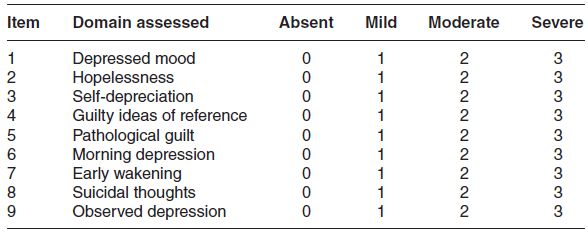

The CDSS contains nine items which are assessed on a four-point response format (‘absent’ to ‘severe’). Eight of the items are completed during a structured interview with the client while the final item (item 9) is based on an overall observation of the entire interview. The domains assessed are outlined in Table 2.2. A total score can be obtained by summing all item scores to provide a total score of between 0 and 27. A total score of 5 or more is suggestive of depression (in those with schizophrenia

Table 2.2 Domains included in the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

- How do you see the future for yourself?

- Can you see any future or has life seemed quite hopeless?

- Have you given up or does there still seem some reason for trying?

| 0 | Absent | |

| 1 | Mild | Has at times felt hopeless over the past week but still has some degree of hope for the future |

| 2 | Moderate | Persistent, moderate sense of hopelessness over the past week |

| 3 | Severe | Persisting and distressing sense of hopelessness |

A glossary is provided for each item to ensure standardisation of the approach followed in the administration of the instrument. The glossary for the hopelessness domain is provided in Box 2.1

Issues for consideration

The CDSS is relatively brief and easy to score, and captures key symptoms of depression in people with schizophrenia. However, it is administered through a structured interview and its developers suggest that users should have at least five practice interviews in the presence of a rater who is experienced in administration of structured instruments before using it alone. Information about the scale and its development can be found in Addington et al. (1993), and a copy of the scale and information on its use can be obtained from www.ucalgary.ca/cdss. The CDSS is copyrighted and permission to use it can be obtained by emailing Dr Donald Addington at addingto@ucalgary.ca. It can be used free of cost by students and non-profit organisations.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was developed over 50 years ago and is now one of the most widely used scales for the assessment of depression. The original version included 17 items but a later version included four additional items considered useful in identifying subtypes of depressive illness. However, these four items are not included in the overall rating of depression and the original 17-item version remains more widely used (Bagby et al., 2004).

While the HDRS (also known as the HAM-D) is usually completed following an unstructured interview, guides are now available to assist in having the scale administered in a semi-structured format (see Williams, 1988). Items are scored on a mixture of three-point and five-point scales and summed to provide a total score (range 0–54). It is now widely accepted that total scores of 6 and lower represent an absence of depression, 7–17 mild depression, 18–24 moderate depression and scores above 24 indicate severe depression. Box 2.2 provides an example of the item structure

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | Self-reproach, feels he/she has let people down |

| 2 | Ideas of guilt or rumination over past errors or sinful deeds |

| 3 | Present illness is a punishment. Delusions of guilt |

| 4 | Hears accusatory or denunciatory voices and/or experiences threatening visual hallucinations |

| 0 | No difficulty falling asleep |

| 1 | Complains of occasional difficulty falling asleep, i.e. more than half an hour |

| 2 | Complains of nightly difficulty falling asleep |

Issues for consideration

The HDRS is one of the scales most widely used for the assessment of depression severity. Nonetheless, it has been criticised for not including all the symptoms associated with depression (such as oversleeping, overeating and weight gain) and for inclusion of items related to other domains such as anxiety. Moreover, there are issues with the heterogeneity of rating descriptors for some items; for example, the depressed mood item contains a mixture of affective, behavioural and cognitive features (Bagby et al., 2004).

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, the HDRS is popular in clinical trials and as a measure of depression severity in clinical practice. The scale can be administered in 20–30 minutes, is easy to score (item scores are summed to provide a total score) and there are established ‘cut-offs’ to indicate levels of depression. However, expertise in the clinical assessment of depression is required, along with training in the use of the scale. There are no restrictions on the use of the scale and copies can be downloaded from http://healthnet.umassmed.edu/mhealth/HAMD.pdf.

Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS)

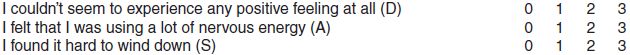

The DASS was developed in Australia (Lovibond, 1998; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) and contains 42 items assessing three separate but related constructs: depression, anxiety and stress. A brief version (21 items) is also available, and scores from it correlate highly with the 42-item scale. Responses options focus on the amount of time in the past week that an individual experiences a given problem, such as ‘I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all’. This and other items are rated on a four-point scale ranging from ‘Did not apply to me at all’ to ‘Applied to me very much or most of the time’. The scale’s structure is outlined in Box 2.3

Issues for consideration

The DASS has the advantage of assessing anxiety and stress (in addition to depression) which are frequently found in people with depression. It is completed by the client which alleviates the need for practitioner training. In the 21-item version, seven items contribute to each of the domains assessed: depression, anxiety and stress. (Each domain in the 42 item version has 14 items.) Item scores in each domain are summed to provide a total score for that domain. The DASS is likely to be more useful in those with less severe problems (i.e. those without psychotic features) as the individual needs to be able to process the statements and provide a response to these. In Australia, the DASS is widely used by general practitioners and other practitioners as a screening tool.

| 0 | Did not apply to me at all |

| 1 | Applied to me to some degree, or some of the time |

| 2 | Applied to me to a considerable degree, or a good part of time |

| 3 | Applied to me very much, or most of the time |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree