CHAPTER 7

Assessment of Spasticity in the Upper Extremity

Thomas Watanabe

A comprehensive assessment of the patient with spasticity is critical to maximize outcome in the treatment of upper extremity spasticity. Although a number of key factors comprise this evaluation, the most important component is the identification of appropriate goals. Once the treatment goals are determined, the clinician can then identify and address barriers to achieving them. These barriers may be identified through physical examination. This evaluation may lead to the need for further diagnostic testing. Awareness of concomitant pathological processes, which may or may not be related to the condition that has led to complications of the upper motor neuron syndrome (UMNS), may lead to the identification of other barriers to achieving goals. Knowledge of functional anatomy, including neurologic and muscular action, will aid in the evaluation and development of an appropriate treatment plan. The arm must be assessed in the context of other needs and goals of the individual, as interventions targeting the arm may affect function or alter the ability to intervene elsewhere. A number of different tools can be used to assess elements of the UMNS as well as function and to objectively demonstrate efficacy of treatments. If interventions for spasticity have already been initiated, the assessment also must include an evaluation of the efficacy of prior interventions. The goal of this chapter is to provide the reader with tools to carry out a comprehensive assessment of the individual with upper extremity spasticity and demonstrate how this assessment can aid in the development of a successful treatment plan.

IDENTIFYING GOALS IN UPPER EXTREMITY ASSESSMENT

Depending on the situation, it may be important to solicit information from a number of different individuals to identify goals. Whenever appropriate, the patient should be the primary person who identifies the goals, but clearly, there are situations in which the patient cannot provide much, if any, information. The patient’s family or other caregivers may be able to identify important goals. Other treating clinicians, including therapists, nurses, aides, or other physicians, may also be useful sources of information regarding goals. As these goals are identified, the clinician will need to make some determination regarding the appropriateness of the goals. There will be times when it will not be possible to determine appropriateness with confidence, but this may become clearer with subsequent evaluations associated with ongoing treatment.

Goal setting is important because goals encourage the treatment team to evaluate and address spasticity, not by its presence or absence but rather by determining whether spasticity is a barrier to achieving the stated goal. There will be occasions where this is not the case and, in fact, the presence of spasticity to a degree may be beneficial in achieving a goal. Spasticity is also only one component of deficits related to upper motor neuron dysfunction; so it is important to assess which aspects of the UMNS are the primary barriers to attaining goals. Taking this approach will help the clinician make decisions regarding what treatment modality or modalities to use. For example, a determination may be made that the most appropriate goal for an individual with severe finger flexor spasticity is positioning to prevent breakdown of skin in the palm. In such a situation, the clinician may choose more aggressive or longer-acting interventions such as surgery if it is determined that there is minimal likelihood of functional use of the hand.

The number of goals that can be generated when assessing upper extremity spasticity are essentially infinite depending on how specific the clinician wants them to be. For patients with a greater degree of impairment, goals may be more related to decreasing the amount of care that providers need to deliver or preventing complications related to relative immobility. Such goals could include maintaining hygiene, improving ease of care for activities of daily living, helping with positioning, preventing breakdown of skin, and minimizing pain. More active goals may include helping the patient to participate in dressing, eating, grooming, or other daily activities. Goals may also be related to improving finer motor activities, such as writing or playing the piano. If feasible, it is important to encourage all participants in the goal-setting process to think about goals that may positively affect activity and participation, rather than the more traditional goals that tend to focus on body functions and structure.

Finally, it is important to identify goals because achievement of these goals is one of the most, if not the most, important measure of efficacy in a spasticity management program. The reevaluation of goals and the setting of new goals should be the focal points of follow-up visits.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS IN ASSESSING THE UPPER EXTREMITY

A proper understanding of the anatomy of the upper limb is essential for assessment of upper extremity spasticity. Although there are a number of stereotypical patterns seen in any arm as part of the UMNS (1), these patterns may involve a number of different muscles or combinations of muscles as shown in Table 7.1. Many muscles carry out more than one function or movement, and this must be taken into account, for instance, when one is considering focal chemodenervation. Otherwise, efforts to address a problem related to movement or positioning at one joint may alter the function pertaining to a different movement. In addition, changes in the position of the limb at one joint may have direct effects on function and movement at another joint, such as with tenodesis.

ASSESSMENT OF THE SHOULDER

The shoulder joint is inherently very unstable. This instability allows for a greater degree of range of motion. As seen in Table 7.1, a number of different muscles are involved in various movements of the shoulder. This makes the evaluation of the shoulder at times quite complex. The initial assessment should include a discussion of problems related to the shoulder, addressing function, ease of care, and other issues, such as pain. The initial examination of the shoulder should include inspection of the joint and skin, identification of areas of tenderness and swelling, and, as appropriate, an assessment of strength and active and passive range of motion. This assessment, which should also be undertaken for the joints discussed in the following, will help the process of identification of goals and will also identify problems that may impair joint function including those not necessarily related to UMNS.

TABLE 7.1

COMMON PATTERNS OF MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY SEEN IN THE UPPER MOTOR NEURON SYNDROME | |

Muscle Pattern | Potentially Involved Muscles |

Shoulder adduction and internal rotation | Pectoralis major, subscapularis, latissimus dorsi, teres major, anterior deltoid |

Elbow flexion | Biceps brachii, brachialis, brachioradialis |

Forearm pronation | Pronator teres, pronator quadrates |

Wrist flexion | Flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum superficialis, and profundus |

Wrist extension | Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis, extensor carpi ulnaris, long finger extensors |

Finger flexion | Flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus (can target specific fascicles), lumbricals |

Thumb-in-palm | Flexor pollicis longus, flexor pollicis brevis, adductor pollicis |

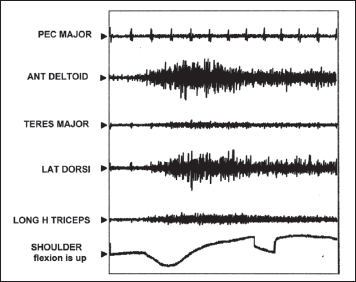

A common pattern seen in the UMNS is the adducted and internally rotated shoulder (1). This position may lead to poor hygiene, breakdown of skin in the axilla, difficulties with dressing and positioning, and pain in the shoulder. Although there are a number of muscles that may contribute to adduction and internal rotation, the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis, and teres major are most commonly involved. In trying to determine the relative contributions of these or other muscles in the adducted and internally rotated shoulder, it may be helpful to remember some of the other actions of each of these muscles. For instance, the latissimus dorsi is also a shoulder extensor as is the teres major. Therefore, when shoulder extension is also noted, one might consider focusing on these muscles. Recall also that the latissimus dorsi is an important shoulder depressor and is important when using crutches. Other muscles that may contribute to excessive shoulder extension include the long head of the triceps, posterior deltoid, teres major, and sternocostal portion of the pectoralis major. Cocontraction of shoulder extensors may inhibit the patient’s ability to voluntarily flex the shoulder (Figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1 Dynamic electromyography demonstrating the co-contraction of the latissimus dorsi as well as the long head of the triceps when the patient is reaching forward, flexing the shoulder. These two shoulder extensors may be targets for focal chemodenervation to improve voluntary shoulder flexion. A third shoulder extensor, the teres major, demonstrates minimal co-contraction. Used with permission from Dr. Nathaniel Mayer.

If, on the other hand, shoulder flexion is seen along with internal rotation and adduction, one might anticipate that the pectoralis major is relatively more active, as the clavicular portion assists in flexing the arm. Other muscles that may contribute to excessive shoulder flexion include the anterior deltoid, coracobrachialis, and biceps brachii. Because these muscles all have other functions, this is another example of the need to consider all of the actions of a particular muscle when considering focal chemodenervation. The subscapularis also deserves mention, as it is in many cases the primary internal rotator of the shoulder, although the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, anterior deltoid, and teres major may also contribute (2).

ASSESSMENT OF THE ELBOW

The general assessment of the elbow is similar to that of the shoulder. Discussion with the patient and caregiver may identify problems, such as poor hygiene in the flexor crease, difficulties with reaching and hand-to-mouth activities, dressing, and pain. The functional examination of the elbow may be more straightforward than the shoulder, as there are only two movements to consider: flexion/extension and pronation/supination. The more common pattern seen in the UMNS is excessive flexion and pronation (1). It is easy to understand how this position would lead to the problems identified earlier (Figure 7.2). Severe flexion may cause maceration and skin breakdown in the flexor crease.

FIGURE 7.2 This patient demonstrates a flexed elbow and pronated forearm. Shoulder adductor tone is also present.

The three main flexors of the elbow are the biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis. There may also be small contributions from the extensor carpi radialis and pronator teres. In determining the role or contributions of the three main flexors, it may be worthwhile to note whether the forearm is supinated or not. Remember that the biceps brachii is the primary supinator. In the nonpathological state, flexion in the pronated position is carried out primarily by the brachialis. A related consideration is that in the case of excessive flexion and pronation, sparing the biceps, when addressing elbow flexion, may help address the pronation. The brachioradialis on the other hand may contribute to the excessive pronation.

The two main pronators of the forearm are the pronator teres and the pronator quadratus. The flexor carpi radialis may also assist in pronation if the wrist is flexed. In the UMNS, it is often difficult to distinguish the relative contributions of the pronator teres and pronator quadratus. It has been suggested that the pronator quadratus may be isolated if pronation in the distal forearm is identified when the forearm is fixed in supination at its midpoint. Clearly, this cannot always be achieved. This is one of many situations in which a diagnostic block may be appropriate.

ASSESSMENT OF THE WRIST

Hyperflexion of the wrist is the more common position seen in UMNS, although hyperextension of the wrist is not rare. Problems seen with exaggerated wrist flexion include difficulties with dressing and pain. Regarding pain, carpal tunnel syndrome is often associated with excessive wrist flexion and therefore should be a consideration in the evaluation (3). The position of the wrist is crucial for hand function, and conversely, changes in tightness of the long finger flexors will affect positioning of the wrist. This is an important concept and may affect surgical decision making as well (4). Excessive extension of the wrist may lead to passive tightness of the finger flexors (tenodesis). It is, therefore, important to incorporate finger positioning in the evaluation of range of motion and function of the wrist and vice versa.

The primary wrist flexors are the flexor carpi radialis and flexor carpi ulnaris. The palmaris longus and abductor pollicis longus may also contribute. As mentioned earlier, the long finger flexors (flexor digitorum superficialis [FDS] and flexor digitorum profundus [FDP]) can also participate in wrist flexion, especially when the fingers are extended. If the wrist is also ulnarly deviated, one may surmise that the flexor carpi ulnaris is more involved (as well as the extensor carpi ulnaris). Flexion with radial deviation may suggest that the flexor carpi radialis is more involved, although there are several other muscles that may contribute to radial deviation, including the abductor pollicis longus, extensor carpi radialis and brevis, and extensor pollicis longus and brevis.

Excessive wrist extension may also be seen in the UMNS. Muscles that may contribute include extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, and extensor carpi ulnaris. As with wrist flexion, extension may be affected by the long finger muscles, such as extensor digitorum, extensor indices, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor digiti minimi.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree