The previous two chapters in this book provide pointers for rehabilitation workers when assessing illness components such as symptoms, impairment and functioning. While assessment of these domains provides important information for planning and evaluation purposes, the focus tends to be on the ‘clinical’ presentation of the individual and the identification of symptoms and functional deficits that need to be ‘fixed’. Clients have been critical of traditional mental health services for paying undue attention to these clinical outcomes and insufficient regard to the subjective, personal and ‘internal’ knowledge of the individual (Glover, 2005).

Over the past 20 years, individuals with mental illness and client advocacy groups have been promoting broader concepts such as recovery, strengths and empowerment. Indeed, these concepts have now become the guiding vision for mental health service delivery (Deegan, 1996; Rapp & Goscha, 2006; Segal et al., 1995). Emerging evidence suggests that a greater focus on these domains is likely to improve the clinical outcomes for people with psychiatric disability (Corrigan, 2006; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2007; Rapp & Goscha, 2006).

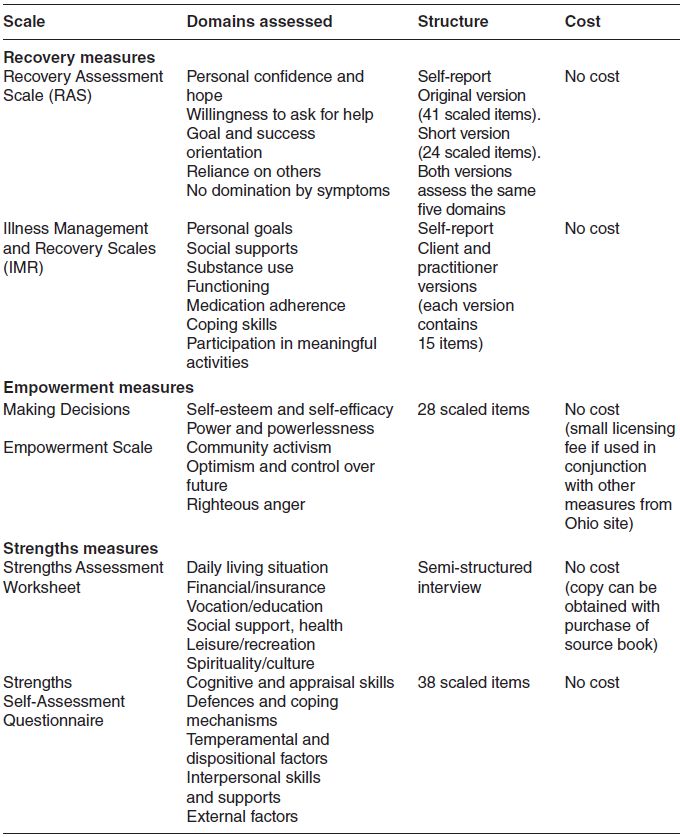

It is becoming increasingly important for practitioners working in the rehabilitation field to include some assessment of these domains in their work with clients. However, unlike the broad range of measures available to assess symptoms and functional impairment, there is a paucity of standardised measures available to assess domains such as empowerment and strengths. From an extensive review of the literature, we have identified two measures that could be used to assess individual recovery, one measure of empowerment and two measures commonly used to assess strengths. These five measures were selected based on their availability, ease of use, brevity and sound psychometric properties (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Recovery, empowerment and strengths measures.

Recovery

The current emphasis on ‘recovery’ has emerged from the lived experience of people with mental illness which suggests that many individuals are able to overcome their difficulties to lead satisfying and contributing lives (Deegan, 1996). This clearly challenges the belief that conditions such as schizophrenia follow a course of progressive deterioration. Common themes in patient accounts of their recovery indicate that recovery involves developing new meaning and purpose in life, taking responsibility for one’s illness, renewing a sense of hope, being involved in meaningful activities, managing symptoms, overcoming stigma and being supported by others (Davidson et al., 2005; Deegan, 1996). Recovery in the mental health context does not necessarily mean ‘cure’ but implies that while individuals with mental illness may continue to experience symptoms and functional impairment, they can move beyond the negative consequences of the illness to achieve greater self-confidence and hope for the future. The concept of recovery provides a fresh approach to the provision of mental health services and is now widely promoted in most developed countries (Anthony, 1993).

While there is currently a growing number of measures designed to assess different aspects of recovery, these tend to be divided into (i) instruments that assess recovery from the perspective of the individual with mental illness, and (ii) instruments that assess the recovery orientation of the mental health services/provider. The measures of recovery included in this chapter focus on recovery from the perspective of the individual. The selection of these recovery measures was guided by the recent review of such measures conducted by Burgess and colleagues (2011). The group used strict selection criteria to short-list measures suitable for routine use with mental health clients. Two of the candidate measures shortlisted by the group, the Recovery Assessment Scale and the Illness Management and Recovery Scales, are described below. Based on the criteria employed by Burgess and colleagues (2011), these two measures assess domains related to personal recovery, are brief, take a client perspective, are suitable for use in routine practice, demonstrate sound psychometric properties and are acceptable to clients.

Recovery Assessment Scale

The Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) was developed in the US by Giffort and colleagues (1995) and is now the most widely used self-report recovery scale for individuals with mental illness (Chiba et al., 2010). The RAS was designed to assess the recovery process of individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. Two versions of the measure are currently available: the original 41-item version (Giffort et al., 1995) and a brief 24-item version (Chiba et al., 2010; Corrigan et al., 2004).

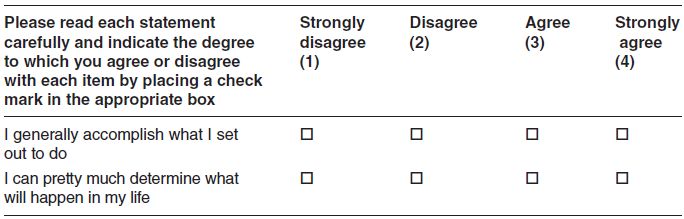

Both versions assess (the same) five domains of recovery that are grounded in the experiences of those with mental illness. All statements are rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to provide a quantitative assessment of recovery. A total scale score is derived from summing the item scores for all items (Table 4.2). Higher scores represent higher self-reported levels of recovery

Both versions of the measure are easy to score and have sound psychometric properties (Chiba et al., 2010; Corrigan et al., 2004; McNaughtet al., 2007). Prior research found a test-retest reliability of r = 0.88 between two administrations 14 days apart and convergent validity with the Empowerment Scale (Rogers et al., 1997). The measure is self-completed by the client and no specific training of the client or person administering the scale is required. The 24-item version of the measure takes 5–10 minutes to complete and yields valuable information for programme evaluation and treatment planning. Information concerning the factor structure of the 41-item version of the measure can be found at: http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/­content/30/4/1005/.full.pdf. Copies of the 24-item version (and information concerning reliability and validity of the measure) can be obtained from the publication by Chiba and colleagues (2010).

Table 4.2 Example of Recovery Assessment Scale items and structure.

Illness Management and Recovery Scales

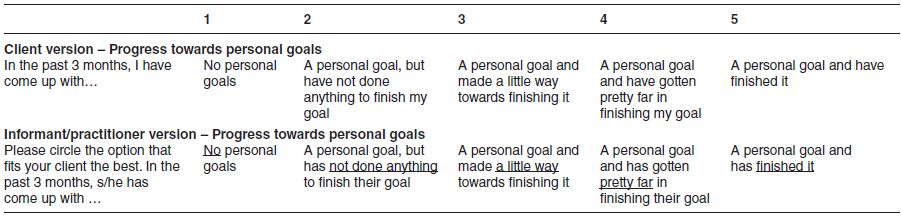

The Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) scales (Mueser et al., 2004) were developed as a repeatable measure that quantifies a patient’s progress towards management of their illness and achieving treatment goals. The IMR scales consider a number of illness management and recovery domains (personal goals, social supports, substance use, functioning, medication adherence, coping skills and participation in meaningful activities) rather than a single construct. The IMR scales have two versions, enabling the assessment of recovery from both practitioner and client perspectives (Table 4.3). Each version contains 15 items/statements, which are rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5). Higher scores represent higher self-reported levels of recovery.

A potential criticism of this measure is that a third of the items relate to more traditional clinical constructs associated with impairment, specifically medication adherence, symptom severity, impairment in functioning, relapse and psychiatric hospitalisation.

Empowerment

Despite the widespread use of the term in the mental health context, empowerment remains poorly understood (Corrigan, 2006). It has been defined as the level of personal control an individual has over important areas of their life, including not only mental health but also vocation, accommodation and relationships (Segal et al., 1995). Empowerment is also closely related to autonomy which is also supported as a recovery ideal.

Empowerment is widely discussed and promoted by client groups and practitioners working in the rehabilitation field. Indeed, it is a key goal of most rehabilitation programmes for those with serious mental illness. Empowerment can be viewed from a broader treatment, organisational or community perspective. This might include activities such as involvement in decision making regarding one’s own treatment or on committees of public mental health services or participation in mental health advocacy groups in the community. These perspectives are also highly consistent with recovery perspectives and have specific measures (e.g. treatment empowerment; see Hudon et al., 2010), but here we limit ourselves to assessment of perceived empowerment around control of one’s life at an individual level.

Table 4.3 Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Scales.

It is clear that empowerment is closely related to strengths and recovery-based practice in that a focus on recovery and strengths is likely to enhance empowerment. However, there is a paucity of measures devoted to the assessment of empowerment in the mental health field. One exception is the Making Decisions Empowerment Scale developed in the US by Young and Ensing (1999). The measure is described in greater detail below.

Making Decisions Empowerment Scale

The Making Decisions Empowerment Scale (commonly called the Empowerment Scale) was developed by a group of mental health clients with input from academics and researchers (Rogers et al., 1997). The measure employs 28 statements/items that can be collapsed into five domains related to client empowerment. Items are rated on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) with no ‘neutral’ option (Table 4.4). Item scores are summed and averaged to provide domain scores and an overall scale score. Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived empowerment. Reliability coefficients for the scale range from 0.73 to 0.85 (Strack et al., 2007).

Since 2003, the Ohio Department of Mental Health has included the Making Decisions Empowerment Scale in the suite of measures used to assess client outcomes. Copies of the scale can be obtained from the Department’s website at: www.mh.state.oh.us/assets/client-outcomes/instruments/english-adult-client.pdf (refer to Section 4 for the items that make up the Empowerment Scale).

Table 4.4 Empowerment Scale: example of items/structure and scoring.