Introduction

While the positive symptoms of psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia tend to plateau and even cease following the active phase of the illness, deficits in functioning (i.e. disability) can continue to accumulate. Indeed, limitations in functioning can represent a significant component of illness burden (Bellack et al., 2006). It is now clear that conditions such as schizophrenia have a pervasive impact across a wide range of life domains. Initial assessment and ongoing monitoring of deficits in functioning using standardised measures should be a major focus of rehabilitation workers. In this chapter we build on the work outlined in the previous chapter (which addressed the assessment of symptoms) and focus on the assessment of functioning.

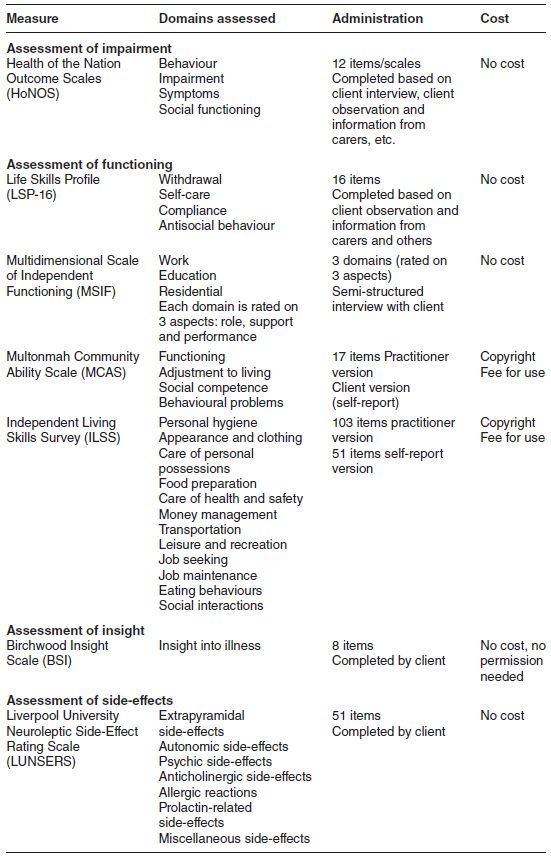

Functioning is a broad and complex construct that encompasses a number of related domains such as role, relationships, leisure, self-care, and physical and psychological health (Mueser & Gingerich, 2006). In addition, there are a number of related factors that can affect functioning such as insight and the impact of medication side-effects. Since there is currently no single scale available to assess all of these constructs, we have identified a range of measures that could be considered for monitoring and evaluation purposes (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Summary of functioning and disability measures.

Assessment of impairment

Health of the Nation Outcome Scales

The Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) were developed in the UK by Wing and associates as a measure of illness severity (Wing et al., 1996) (Box 3.1). The HoNOS comprise 12 separate but related scales, which address problems in four areas.

- Behavioural problems (aggression, self-harm and substance use)

- Impairment (cognitive and physical)

- Symptomatic problems (hallucinations/delusions, depression and other symptoms)

- Social problems (relationships, daily living, housing and work)

Each scale is rated from 0 (‘no problem’) to 4 (‘severe to very severe problem’). The total score for all 12 scales ranges from 0 to 48 where higher scores represent greater overall severity. The rating period is usually the previous 2 weeks.

The HoNOS has been validated in Canada (Kisely et al., 2006), the UK (Bebbington et al., 1999) and Australia (Trauer et al., 1999). Indeed, the HoNOS is now included in the suite of measures used in Australia to monitor outcomes for clients in receipt of mental health services.

Issues for consideration

The HoNOS is completed by a mental health professional following an interview with the individual being rated. In most cases, the client will be able to provide sufficient information to complete the HoNOS. However, in situations where the client is unwilling or unable to participate in the assessment, the rater will need access to information from a relative or carer. For example, Scale 1 asks for information about aggressive incidents in the past 2 weeks. Clients may be unwilling to discuss this and additional information from a carer may be required.

While the instrument appears to be relatively straightforward, its completion can be demanding. Clinical judgement is required and the rater will also need to consult a glossary as each scale is being completed. Face-to-face training using the programme developed by the College of Psychiatrists is recommended. In addition, copyright in the scale is owned by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and permission to use the scale must be obtained from the College. The contact is:

Do not include physical illness or disability due to alcohol or drug use, rated in item 5.

| 0 | No problem of this kind during the period rated |

| 1 | Some overindulgence but within social limits |

| 2 | Loss of control of drinking or drug taking, but not seriously addicted |

| 3 | Marked craving or dependence on alcohol or drugs with frequent loss of control, risk taking under the influence (e.g. drunk driving) |

| 4 | Incapacitated by alcohol/drug problems |

The Training Program Manager

Royal College of Psychiatrists

17 Belgrave Square

London, SW1X 8PG

email: egeorge@rcpsych.ac.uk

Those interested in the HoNOS may wish to visit http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/training/honos.aspx for a more in-depth discussion of the measure and training requirements.

Assessment of daily functioning

Disability associated with disorders such as schizophrenia can have a major impact on one’s ability to perform basic self-care activities. Understanding the challenges that individuals have in meeting the basic necessities of life (cooking, cleaning, shopping, managing finances, meeting healthcare needs, etc.) will form a key component of any rehabilitation assessment. A wide range of measures is now available to assess these areas of functioning and a selection of those more commonly used in in the rehabilitation field, are discussed below. The focus is on those applicable to those with severe disability. Some are self-rated by the client whereas others are completed by the rehabilitation worker.

The Life Skills Profile

The Life Skills Profile (LSP) was developed in Australia as a multidimensional measure of functioning and disability in people with schizophrenia (Rosen et al., 1989). However, the LSP is now applied more broadly since many of the ‘skills’ assessed are also relevant in other psychotic and organic conditions. The LSP is rated by a practitioner using observable behaviours rather than clinical assessment or interview.

Three versions of the LSP have emerged: the LSP-39 (original version), the LSP-20 and LSP-16. The original 39-item version was found to be rather lengthy for routine use by practitioners and this led to the development of the two briefer versions (Trauer et al., 1995). The LSP-16 was developed as a measure of outcome for the Mental Health Classification and Service Costs Project, a case-mix initiative implemented in Australia in 1996 (see www.mnhocc.org). The 16-item version is included in the suite of measures currently used to monitor client outcomes in Australian mental health services (Meehan et al., 2006).

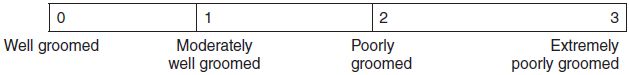

The 16 items are summed to yield four subscales (withdrawal, self-care, compliance and antisocial behaviour) and a total scale score. Items are scored 0–3 where ‘0’ represents low levels of dysfunction and ‘3’ represents high levels (Box 3.2).

Issues for consideration

The Life Skills Profile is a useful measure for the assessment of rehabilitation outcomes since aspects of functioning (‘life skills’) rather than symptoms are assessed. Indeed, the domains assessed via the LSP (withdrawal, self-care, compliance and antisocial behaviour) will often be the focus of rehabilitation efforts. Unlike some of the other measures reviewed, the LSP can be used to assess those attending both inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation programmes. The period covered by the scale is the previous 3 months and the rater needs to be familiar with the functioning of the client over that period. The measure can be used by clinical and non-clinical raters and no specific training is required as the measure has well-described anchor points. While there are currently three versions of the scale in use, these are scored differently and, when comparing findings with published reports in the literature, it is important to check that the version you are using is similar to that used in the published report.

Copies of the LSP-39, LSP-20 and LSP-16 and other relevant information concerning the structure and scoring of the different versions of the scale can be downloaded from http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/research/tools/index.cfm.

Multidimensional Scale of Independent Functioning

The Multidimensional Scale of Independent Functioning (MSIF) is a relatively new instrument for rating functional disability in psychiatric outpatients (Jaeger et al., 2003). The scale captures a 1-month time period and is completed by a mental health professional following a semi-structured interview with the individual being rated. The interview guide is available from the authors of the scale (see details below).

The interview provides for a thorough analysis of the person’s day-to-day activities in each of the three domains:

- work (e.g. competitive, supported, dependent care, volunteer)

- education (e.g. college, vocational or certificate school, rehabilitation training programme)

- residential (e.g. where the person is living, what responsibilities the person has).

If the individual is working and in training, both work and training are rated. However, education is rated only if the individual is enrolled in training/education. Similarly, work is rated if the client is in some form of work.

Each of the three domains (work, education and residential) are coded according to a detailed set of anchors to provide an assessment of (i) role, (ii) support and (iii) performance for each of the three domains. For example, when the ‘work’ domain is assessed, the rater would consider the job title, the type of work carried out, when and at what pace tasks are performed, the level of supervision required, the level of assistance required, and the overall performance standard of the work. Each dimension is rated along a seven-point Likert scale (1 = normal functioning to 7 = total disability). Global ratings can be obtained for each domain (work, education, residential) and for each dimension (role, support and performance). Finally, a global rating (total scale score) can be obtained for overall functioning.

Issues for consideration

While this is a relatively complex measure, it provides a more comprehensive assessment of work, education and living arrangements than most of the other instruments reviewed. The provision of extensive detail for each anchor point reduces the need for rater interpretation/judgement and increases inter-rater agreement. No specific training is required to use the measure. The collection of information concerning support and performance improves the ability of the scale to differentiate between higher and lower functioning individuals. This feature of the MSIF improves its capacity to identify change following clinical interventions and makes it particularly useful in the evaluation of rehabilitation programmes that focus on improving work, training and residential capacity. Follow-up assessments can be conducted via telephone and provide information on changes in role position, level of support required, and performance level achieved. The scale was developed for outpatients and captures a 1-month timeframe (this can be adapted to monitor a longer period). A detailed description of the MSIF is provided in the article published in Schizophrenia Bulletin by Jaeger et al. (2007).

The interview schedule and copies of the MSIF can be obtained without cost from:

Professor Judith Jaeger

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences

Zucker Hillside Hospital

75–59 263rd Street

Glen Oaks, NY 11004

email: jaeger.ju@comcast.net

Multonmah Community Ability Scale

The Multonmah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (Barker et al., 1994) was designed to assess the level of functioning in clients with more severe disability living in community settings. The scale contains 17 practitioner-rated items that can be collapsed into four subscales or domains of functioning.

- Interference in Functioning (five items focusing on physical health, mental health, intellectual health)

- Adjustment to Living (three items dealing with daily living skills and money management)

- Social Competence (five items that assess social interest and skills)

- Behaviour Problems (four items that assess participation in treatment, substance use and acting-out behaviours)

The rating period for items in the first three domains is the past 3 months while the fourth domain assesses functioning in the past 12 months. All items are scored on a five-point scale and item scores are summed to provide a domain score and total scale score (Box 3.3). Barker and colleagues (1994) suggest that total scale scores of 17–47 indicate severe disability, 48–62 represent medium disability, and 63–85 indicate little or no disability. The measure has high predictive validity – individuals with lower scores were more likely to be hospitalised at some time in the future (Hampton & Chafetz, 2002). The measure has adequate inter-rater and test-retest reliability (Trauer, 2001).